Headaches

Although most headache presentations to the ED are of benign etiology, there are several potentially life-threatening conditions for which the emergency physician should have a high index of suspicion based on symptoms. This special feature reviews migraine, thunderclap headache, and uncommon—but potentially serious and life-threatening—causes of headache.

Conclusion

In spite of being diligent, performing a good history and physical examination, and providing appropriate follow-up, EPs will sometimes “miss” serious and unusual causes of headaches. Current topics in headache diagnosis and management of migraine, thunderclap, and unusual causes of headache are examined in this special feature to help the EP in the diagnostic decision-making process.

Dr Huff is a professor of emergency medicine and neurology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

Migraine: An Evidence-Based Update

Rebecca H. Nerenberg, MD; Benjamin W. Friedman, MD

Multiple regimens have been shown effective in treating migraine with and without aura in both the acute-care and outpatient setting.

Recurrent episodic primary headache disorders such as migraine, tension-type, and cluster headache are a common presentation to the ED, with an estimated number of 5 million patients in the United States presenting annually.1 For these headaches, it is essential that the emergency physician (EP) focus on rapid and effective treatment, while minimizing side effects and expediting a return to work and usual activities.

Emergency physicians are adept at ruling-out serious secondary headaches (eg, bacterial meningitis, aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage) and identifying benign secondary causes (eg, acute rhinosinusitis, cervicogenic headache). Migraine, the focus of this review, is the primary headache disorder that most commonly results in an ED visit.

Symptoms

Though presentations may be quite varied, migraine typically presents as a pulsating, unilateral headache, and is associated with nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia, and osmophobia.2 The condition is often described as severe in intensity and functionally impairing—characteristics that contribute to so many ED visits. Migraine, however, also may present bilaterally and be associated with muscle pain or spasms.

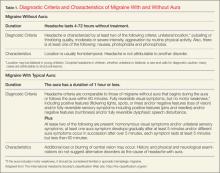

It is the constellation of symptoms—rather than any one symptom in particular—that leads to the correct diagnosis. Classically, the prodromal aura, which is reported by fewer than 20% of patients, precedes the onset of headache pain by no more than 1 hour and resolves by the time the headache begins. Many migraine patients, however, report visual or sensory disturbances during the headache phase itself. Other prodromal symptoms such as change in mood (eg, depression, sense of well-being, euphoria) and appetite commonly precede the acute headache by several days. Table 1 provides diagnostic criteria and characteristics of migraine with aura and without aura.

Pathophysiology

Although the mechanism of migraine is not completely understood, it is clear that vascular dysfunction alone does not adequately explain its pathophysiology. Migraine is not primarily a vascular headache, but rather it is fundamentally a brain disorder. The condition is best explained as a dysfunctional pain response to an as yet unidentified trigger that does not appear to cause tissue damage or otherwise threaten the body or brain.

In migraine, normally nonnoxious stimulation, such as light, sound, and touch, is perceived as painful. The trigeminal nerve is activated inappropriately and is a central component of activated pain pathways. Cortical spreading depression, a slow gap-junction mediated wave of depolarization causing changes in vascular and neural function, is associated with migraine aura. It is not yet understood why migraine attacks begin, and research to understand the migraine brain is ongoing.3

Diagnosis

Given the high prevalence of patients with migraine presenting to EDs and the relatively uncommon occurrence of malignant secondary headaches, migraine can often be correctly diagnosed based solely on specific historical features of the headache and/or the answers to a simple questionnaire. One of the best simple predictors of migraine is the POUNDing mnemonic:

- Pulsating headache quality;

- Duration of 4 to 72 hours;

- Unilateral pain;

- Nausea; and

- Disabling pain.

Patients with three or four of the above features can be diagnosed as having a migraine headache with high sensitivity and specificity.4 The combination of functional disability, nausea, and sensitivity to light has a high positive predictive value for a diagnosis of migraine among patients with recurrent episodes of headache.5

Having a short list of specific symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of migraine is helpful in a busy ED. These symptom checklists allow the health care provider to make a more specific diagnosis in a patient with a recurrent headache disorder. However, distinguishing among the various types of primary headache disorders prior to treatment is often unnecessary for the EP since acute migraine and tension-type headaches are likely to respond to similar treatments such as sumatriptan,6 the antiemetic dopamine antagonists,7 and parenteral ketorolac.

Treatment

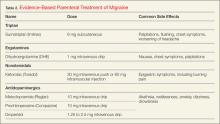

The EP has a large and varied armamentarium for treating acute migraine. First-line parenteral choices include migraine-specific medications (eg, sumatriptan, dihydroergotamine), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (eg, ketorolac), and the various antiemetic dopamine antagonists (Table 2).