Factors Affecting Academic Leadership in Dermatology

Although prior studies have examined methods by which to recruit and retain academic dermatologists, few have examined factors that are important for developing academic leaders in dermatology. This study sought to examine characteristics of dermatology residency programs that affect the odds of producing department or division chairs/chiefs and program directors (PDs). Data regarding program size, faculty, grants, alumni residency program attended, lectures, and publications for all accredited US dermatology residency programs were collected. Of the 103 programs examined, 46% had graduated at least 1 chair/chief, and 53% had graduated at least 1 PD. Results emphasize that faculty guidance and research may represent modifiable factors by which a dermatology residency program can increase its graduation of academic leaders.

Practice Points

- Leadership in dermatology is key to the future of academics.

- Opportunity for mentorship and research are the most important residency program factors leading to the graduation of future chairs/chiefs and program directors.

- The retention of residents and young faculty in academics can be aided by research and scholarly activity.

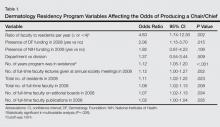

Factors that had the highest effect on the odds of a program graduating a chair/chief included the ratio of faculty to residents per year, presence of DF funding in 2008, number of years program was in existence, number of residents, number of full-time faculty, and number of full-time faculty on editorial boards of 6 major dermatology journals (Table 1). When controlling for each of these variables in the final multivariable analysis, programs with 4 or more faculty per resident had 3.31 times the odds of producing a chair/chief (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.14-9.66; P=.028).

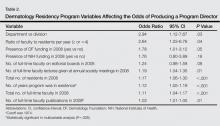

Factors that had the highest effect on the odds of a program graduating a PD included status as department versus division, ratio of faculty to residents per year, presence of DF funding in 2008, number of lectures given by full-time faculty members at annual society meetings, number of residents, number of years program was in existence, number of full-time faculty, and number of publications from full-time faculty members (Table 2). The most significant factor associated with graduating PDs after controlling for other variables was the number of publications from full-time faculty members. The odds increased by 3.2% for every 1 additional publication and 32% for every 10 additional publications (95% CI, 1.01-1.06; P=.026).

Multiple linear regression demonstrated a positive relationship between the number of graduating chairs/chiefs and total full-time faculty members (R2=0.26; P=.034) and ratio of full-time faculty to residents (R2=0.29; P<.001). Marginally significant correlations were seen between the number of PDs and ratio of full-time faculty to residents (R2=0.32; P=.05) as well as the number of publications from full-time faculty members (R2=0.32; P=.05).

Comment

The ratio of full-time faculty to residents increased a program’s odds of graduating a chair/chief. More faculty members may lead to more opportunities for mentorship of residents and young faculty. Mentors are widely perceived to be integral to the learning and development of residents, not only in dermatology5 but across all specialties.6 Mentors also have been noted to play a key role in bolstering and maintaining interest in academics,7 which is true not only with regard to recruiting new residents but for retaining young faculty members. In a study (N=109) that examined factors associated with residents’ loss of interest in academic careers, half of the participants reported a lack of effective mentors, role models, and professional guidance.8 Mentors provide teaching, supervision, and advice, especially with regard to research and career paths.9 A large number of faculty members provides more opportunities for direct mentorship and offers residents more exposure to research, specialty clinics, and academic philosophies, which may positively influence and even inspire academic pursuits and leadership.3

Although the solution to producing future chairs/chiefs and PDs may lie in faculty guidance, finding and retaining faculty members as mentors amidst a shortage of academic dermatologists presents an underlying issue.3 In addition to a lack of mentorship, residents cite bureaucracy, salary differentials, and location to explain a loss of interest in academic careers.8 Several programs have been developed to address the recruitment of dermatology residents for academic careers, including combined medical-dermatology programs, 2+2 programs (2 years of clinical residency plus 2 additional research years), clinical research fellowships,10 and the Society for Investigative Dermatology’s Dermatology Resident Retreat for Future Academicians (https://www.sidnet.org/fortraineesandresidents).11 Perhaps recruitment should even start at the medical student level. In light of the academic strength of the current pool of dermatology residency applicants,12 training programs should continue to screen for applicants with sincere interests in academia.13 Students with more research and publications may be more likely to pursue academic careers, in accordance with prior studies of dermatology trainees.3,14 Studies also have shown that graduates of foreign dermatology residencies15 and individuals who hold both MD and PhD degrees may be more likely to enter into academic careers.16

For creating future chairs/chiefs and PDs, retention of young faculty in academics is as important as recruiting residents.17 At the mid-career level, the decline of funds for research has generated pressure for academic physicians to see increasing numbers of patients, leaving insufficient time for the many duties that accompany academic posts,2 including teaching and publishing. Other reasons that faculty members leave their posts before 40 years of age include financial and family concerns18 as well as the desire for more autonomy.4 Formalized training is seen with the American Academy of Dermatology’s Academic Dermatology Leadership Program (https://www.aad.org/members/leadership-institute/mentoring/aad-mentoring-opportunities/academic-dermatology-leadership-program-mentee), which promotes advanced leadership training to recent graduates.5 Other methods include support of young faculty with mentorship; grant applications; and administration at the department, hospital, and government levels.17 Recruitment of faculty from private practice may represent another potential source of faculty who wish to pursue more scholarly endeavors.4 Teaching has been cited as a primary reason for faculty members to remain in academia,18 and thus time for teaching must be protected. Such a strategy is in accordance with our findings that amount of annual DF funding received, number of full-time faculty publications, number of faculty members on editorial boards of major dermatology journals, and number of lectures given by full-time faculty factors at annual society meetings are positively associated with the odds of producing chairs/chiefs or PDs. In particular, the number of full-time faculty publications is directly related to increased odds of graduates becoming PDs. Residents and young faculty members who take part in research and attend national conferences may find inspiration or develop a passion for academic leadership.