Disseminated Cryptococcosis in a Diabetic Patient

Cryptococcosis is an opportunistic infection caused by Cryptococcus neoformans that typically presents in immunocompromised patients, most commonly in those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. It rarely has been described in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM). Defects in the host defense mechanisms due to hyperglycemia predispose diabetic patients to opportunistic infections such as cryptococcosis. We present a rare case of disseminated cryptococcosis in a 48-year-old HIV-negative man with DM.

Practice Points

- Uncontrolled diabetes mellitus can be an important etiological factor for disseminated cryptococcosis.

- Cryptococcosis in human immunodeficiency virus–negative patients tends to have less severe clinical manifestations and better prognoses versus in patients who are human immunodeficiency virus positive.

It occasionally has been documented in patients with DM.3 Hyperglycemia is known to cause impaired polymorphonuclear chemotaxis, abnormal phagocytosis, poor blast transformation of lymphocytes, and defective opsonization. The level of hyperglycemia has a direct influence on microbicidal function of macrophages. Temporary high glucose levels (eg, 200 mg/dL) can substantially impair the respiratory burst of macrophages. In a series of 40 HIV-negative patients with cryptococcosis, 14% (5/37) had DM as a predisposing factor.8 In another series of 94 HIV-negative patients with cryptococcal meningitis, 8.5% (8/94) had DM.9

After entry into the respiratory system, Cryptococcus can lead to latent infection or acute disease depending on the immune status of the host. Disseminated cryptococcosis is defined as the recovery of C neoformans from blood, sterile body fluids, or tissues other than pulmonary tissue.6 Hematogenous dissemination occurs most commonly to the central nervous system (CNS). The skin is the most common site for extraneural dissemination and has been reported in 10% to 20% of patients.5 Cuta-neous cryptococcosis may be present for 2 to 8 months before development of systemic signs of infection, providing a window of opportunity for treatment of patients before fatal effects of dissemination occur.

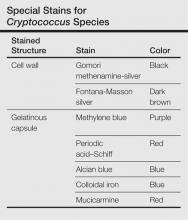

Cutaneous manifestations of cryptococcosis are variable and can include papules, pustules, ulcerated nodules, molluscoid lesions, and cellulitis.5 Acneform lesions as well as lesions resembling erythema nodosum, Kaposi sarcoma, keratoacanthoma, and herpes virus infection also have been described in the literature. Lesions most commonly are located on the head and neck.5 The 2 types of histologic reactions seen in cryptococcal infections are gelatinous and granulomatous, which can occur individually or simultaneously. Gelatinous reactions show numerous spores with large polysaccharide capsules and little tissue reaction. In contrast, granulomatous reactions show pronounced tissue reactions consisting of histiocytes, giant cells, lymphoid cells, and fibroblasts with few spores, which are mainly found within giant cells and histiocytes and occasionally are free in the tissue.5Cryptococcus neoformans is a round to ovoid spore measuring 4 to 12 µm in gelatinous reactions and 2 to 4 µm in granulomatous reactions. Special stains are helpful for demonstration of Cryptococcus species (Table). Diagnosis of cryptococcosis also may be made by india ink staining, KOH preparation, or gram staining of a smear from the lesion. Culture on Sabouraud dextrose agar also can be performed to confirm the species. Detection of cryptococcal capsular polysaccharide antigen in serum and body fluids by latex agglutination test or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay is useful for diagnostic as well as a prognostic evaluation.2 Because cutaneous cryptococcosis usually represents hematogenous dissemination from an internal focus, investigation to detect other organ involvement, especially the CNS, is mandatory.

The gold standard for treatment of severe cryptococcosis and CNS involvement is intravenous amphotericin B (0.7–1 mg/kg daily [total, 1–2 g]) with or without intravenous flucytosine (100 mg/kg daily) for 2 weeks,2 which is followed by treatment with oral fluconazole (400 mg daily) for 10 weeks. In cases with renal dysfunction, liposomal amphotericin B (4–6 mg/kg daily) is a better alternative. In other mild to moderate cases, only fluconazole or itraconazole (400 mg daily) for 6 to 12 months is sufficient for resolution of lesions, as in the case of our patient. Long-term suppressive treatment with fluconazole is essential in HIV-positive patients with low CD4 counts.2

Cryptococcosis in HIV-negative patients differs from HIV-positive patients. Central nervous system and extrapulmonary involvement is less common in HIV-negative patients. Response to treatment often is brisk and mortality is much lower in HIV-negative patients.10 Patients who are HIV negative exhibit a greater inflammatory response with a lesser organism load; however, an exaggerated immune response resulting in higher cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis and protein rarely may result in fatal outcomes.11 Our case emphasizes the need for physicians to consider cryptococcosis in the differential diagnosis of neurologic and cutaneous manifestations in DM.