Impact of Ketogenic and Low-Glycemic Diets on Inflammatory Skin Conditions

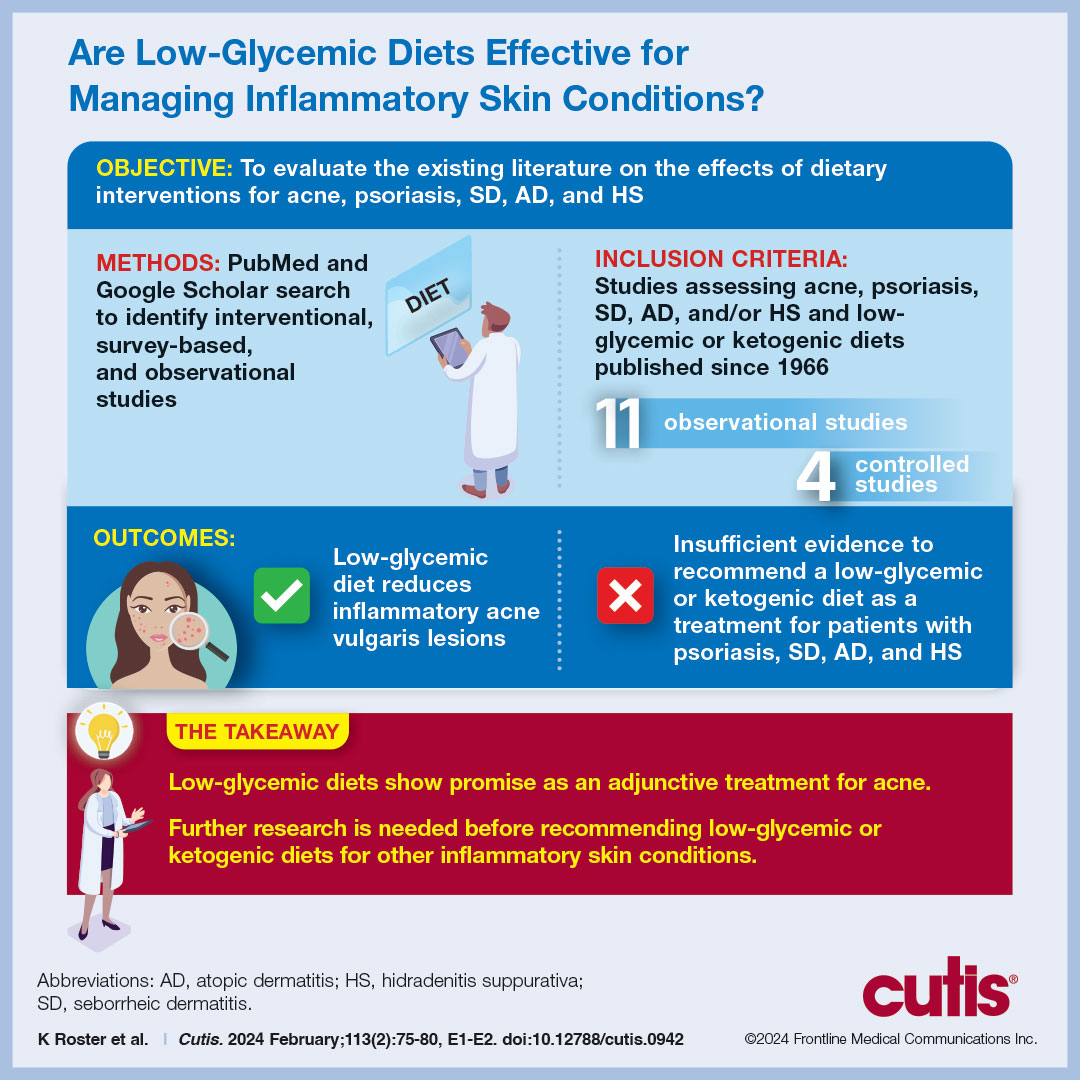

Diet plays an emerging role in dermatologic therapy. The ketogenic and low-glycemic diets have potential anti-inflammatory and metabolic effects, making them attractive for treating inflammatory skin conditions. We provide an overview of the current evidence on the effects of ketogenic and low-glycemic diets on inflammatory skin conditions including acne, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis (SD), atopic dermatitis (AD), and hidradenitis suppurativa (HS). We conclude that low-glycemic diets show promise for treating acne, while the evidence for ketogenic diets in treating other inflammatory skin conditions is limited. Randomized clinical trials are needed to explore the efficacy of these diets as stand-alone or adjunctive treatments for inflammatory skin conditions.

Practice Points

- As the ketogenic diet gains in popularity, dermatologists may inform patients that there is emerging evidence supporting the idea that low-glycemic diets may contribute to improvement in inflammatory skin conditions.

- Dermatologists may educate patients about the potential benefits of a low-glycemic diet as a supplementary treatment for acne based on existing evidence.

- Current evidence is insufficient to endorse a ketogenic diet as superior to other dietary approaches in treating inflammatory skin conditions.

Smith et al18 randomized 43 male patients aged 15 to 25 years with facial acne into 2 cohorts for 12 weeks, each consuming either a low-glycemic diet (25% protein, 45% low-glycemic food [fruits, whole grains], and 30% fat) or a carbohydrate-dense diet of foods with medium to high GI based on prior documentation of the original diet. Patients were instructed to use a noncomedogenic cleanser as their only acne treatment. At 12 weeks, patients consuming the low-glycemic diet had an average of 23.5 fewer inflammatory lesions, while those in the intervention group had 12.0 fewer lesions (P=.03).18

In another controlled study by Kwon et al,21 32 male and female acne patients were randomized to a low-glycemic diet (25% protein, 45% low-glycemic food, and 30% fat) or a standard diet for 10 weeks. Patients on the low-glycemic diet experienced a 70.9% reduction in inflammatory lesions (P<.05). Hematoxylin and eosin staining and image analysis were performed to measure sebaceous gland surface area in the low-glycemic diet group, which decreased from 0.32 to 0.24 mm2 (P=.03). The sebaceous gland surface area in the control group was not reported. Moreover, patients on the low-glycemic diet had reduced IL-8 immunohistochemical staining (decreasing from 2.9 to 1.7 [P=.03]) and sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 levels (decreasing from 2.6 to 1.3 [P=.03]), suggesting suppression of ongoing inflammation. Patients on the low-glycemic diet had no significant difference in transforming growth factor β1(P=.83). In the control group, there was no difference in IL-8, sterol regulatory element binding protein 1, or transforming growth factor β1 (P>.05) on immunohistochemical staining.21

Psoriasis—Psoriasis is a systemic inflammatory disease characterized by hyperproliferation and aberrant keratinocyte plaque formation. The innate immune response of keratinocytes in response to epidermal damage or infection begins with neutrophil recruitment and dendritic cell activation. Dendritic cell secretion of IL-23 promotes T-cell differentiation into helper T cells (TH1) that subsequently secrete IL-17 and IL-22, thereby stimulating keratinocyte proliferation and eventual plaque formation. The relationship between diet and psoriasis is poorly understood; however, hyperinsulinemia is associated with greater severity of psoriasis.31

Four observational studies examined sugar intake in psoriasis patients. Barrea et al23 conducted a survey-based study of 82 male participants (41 with psoriasis and 41 healthy controls), reporting that PASI score was correlated with intake of simple carbohydrates (percentage of total kilocalorie)(r=0.564, P<.001). Another study by Yamashita et al27 found higher sugar intake in psoriasis patients than controls (P=.003) based on surveys from 70 patients with psoriasis and 70 matched healthy controls.

These findings contrast with 2 survey-based studies by Johnson et al22 and Afifi et al25 of sugar intake in psoriasis patients using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Johnson et al22 reported reduced sugar intake among 156 psoriasis patients compared with 6104 unmatched controls (odds ratio, 0.998; CI, 0.996-1 [P=.04]) from 2003 to 2006. Similarly, Afifi et al25 reported decreased sugar intake in 1206 psoriasis patients compared with sex- and age-matched controls (P<.0001) in 2009 and 2010. When patients were asked about dietary triggers, 13.8% of psoriasis patients reported sugar as the most common trigger, which was more frequent than alcohol (13.6%), gluten (7.2%), and dairy (6%).25

Castaldo et al29,30 published 2 nonrandomized clinical intervention studies in 2020 and 2021 evaluating the impact of the ketogenic diet on psoriasis. In the first study, 37 psoriasis patients followed a 10-week diet consisting of 4 weeks on a ketogenic diet (500 kcal/d) followed by 6 weeks on a low-caloric Mediterranean diet.29 At the end of the intervention, there was a 17.4% reduction in PASI score, a 33.2-point reduction in itch severity score, and a 13.4-point reduction in the dermatology life quality index score; however, this study did not include a control diet group for comparison.29 The second study included 30 psoriasis patients on a ketogenic diet and 30 control patients without psoriasis on a regular diet.30 The ketogenic diet consisted of 400 to 500 g of vegetables, 20 to 30 g of fat, and a proportion of protein based on body weight with at least 12 g of whey protein and various amino acids. Patients on the ketogenic diet had significant reduction in PASI scores (value relative to clinical features, 1.4916 [P=.007]). Furthermore, concentrations of cytokines IL-2 (P=.04) and IL-1β (P=.006) decreased following the ketogenic diet but were not measured in the control group.30

Seborrheic Dermatitis—Seborrheic dermatitis is associated with overcolonization of Malassezia species near lipid-rich sebaceous glands. Malassezia hydrolyzes free fatty acids, yielding oleic acids and leading to T-cell release of IL-8 and IL-17.32 Literature is sparse regarding how dietary modifications may play a role in disease severity. In a survey study, Bett et al17 compared 16 SD patients to 1:2 matched controls (N=29) to investigate the relationship between sugar consumption and presence of disease. Two control cohorts were selected, 1 from clinic patients diagnosed with verruca and 1 matched by age and sex from a survey-based study at a facility in London, England. Sugar intake was measured both in total grams per day and in “beverage sugar” per day, defined as sugar taken in tea and coffee. There was higher total sugar and higher beverage sugar intake among the SD group compared with both control groups (P<.05).17