Granulomatous Facial Dermatoses

Noninfectious facial papular granulomas can be the presentation of several conditions, including granulomatous periorificial dermatitis, granulomatous rosacea, lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei, and papular sarcoidosis. Although these entities are treated distinctly from one another, they share several clinical and histological characteristics. We present 2 cases of facial papular granuloma: one patient presented with granulomatous rosacea, and the other had a presentation consistent with sarcoidosis but also demonstrated features of granulomatous periorificial dermatitis and had a protracted course of treatment. Such cases exemplify heterogeneity in the evaluation and management of this cutaneous lesion and highlight the necessity of appreciating its various potential causes.

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should be aware that noninfectious granulomatous dermatosis of the face can be caused by granulomatous periorificial dermatitis, granulomatous rosacea, lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei, and papular sarcoidosis.

- These conditions lie on a spectrum, suggested by their historical description and clinical and histological features.

- Because their clinical courses can vary considerably from patient to patient, a thorough effort should be made to differentiate these conditions.

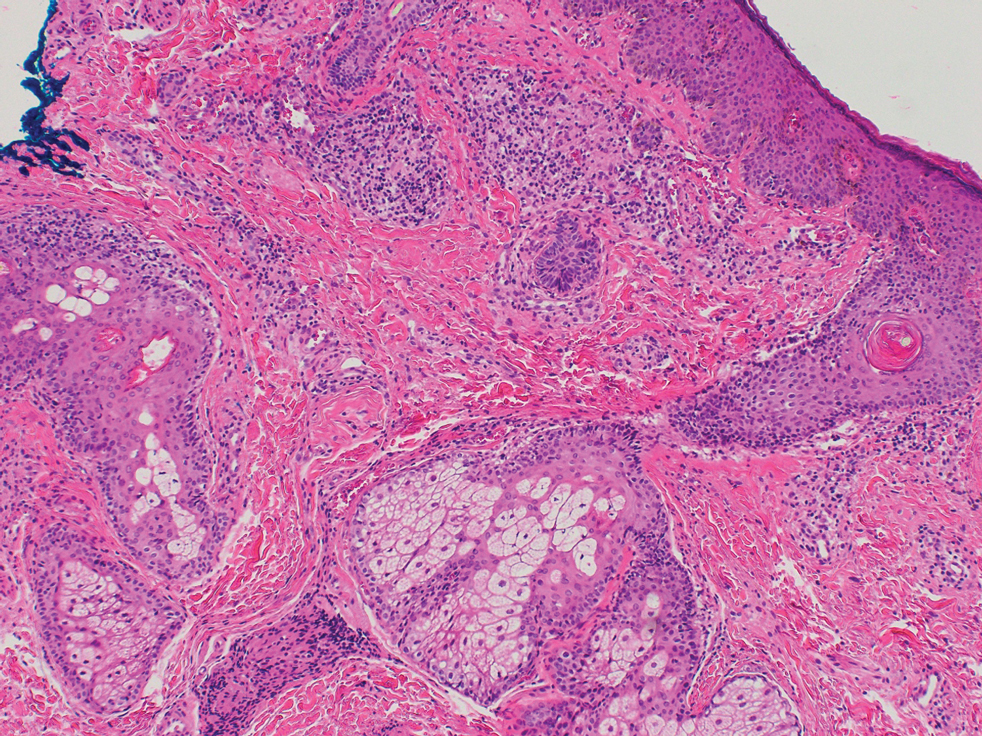

Biopsy of a papule from the left mandible showed superficial vascular telangiectasias, noncaseating granulomas comprising epithelioid histiocytes and lymphocytes in the superficial dermis, and a perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 5). No organisms were identified on Fite or Gomori methenamine silver staining.

Comment

The first step in differentiating cutaneous granulomatous lesions should be to distinguish infectious from noninfectious causes.1 Noninfectious cutaneous granulomas can appear nearly anywhere; however, certain processes have a predilection for the face, including GPD, GR, LMDF, and papular sarcoidosis.5-7 These conditions generally present with papular granulomas with features as described above.

Granulomatous Periorificial Dermatitis—In 1970, Gianotti and colleagues8 briefly described the first possible cases of GPD in 5 children. The eruption comprised numerous yellow, dome-shaped papules in a mostly perioral distribution. Tuberculin and the Kveim tests were nonreactive; histopathology was described as sarcoid-type and not necessarily follicular or perifollicular.8 In 1974, Marten et al9 described 22 Afro-Caribbean children with flesh-colored, papular eruptions on the face that did not show histologic granulomatous changes but were morphologically similar to the reports by Gianotti et al.8 By 1989, Frieden and colleagues10 described this facial eruption as “granulomatous perioral dermatitis in children”. Additionally, the investigators observed granulomatous infiltrates in a perifollicular distribution and suggested follicular disruption as a possible cause. It was clear from the case discussions that these eruptions were not uncommonly diagnosed as papular sarcoidosis.10 The following year, Williams et al11 reported 5 cases of similar papular eruptions in 5 Afro-Caribbean children, coining the term facial Afro-Caribbean eruption.11 Knautz and Lesher12 referred to this entity as “childhood GPD” in 1996 to avoid limiting the diagnosis to Afro-Caribbean patients and to a perioral distribution; this is the most popular current terminology.12 Since then, reports of extrafacial involvement and disease in adults have been published.13,14

Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis often is seen in the perinasal, periocular, and perioral regions of the face.2 It is associated with topical steroid exposure.5 Histologically, noncaseating granulomas around the upper half of undisrupted hair follicles with a lymphocytic infiltrate are typical.13 Treatment should begin with cessation of any topical steroids; first-line agents are oral tetracycline or macrolide antibiotics.5 These agents can be used alone or in combination with topical erythromycin, metronidazole, or sulfur-based lotions.13 Rarely, GPD presents extrafacially.13 Even so, it usually resolves within 2 weeks to 6 months, especially with therapy; scarring is unusual.5,13,15

Granulomatous Rosacea—A report in the early 20th century described patients with tuberculoid granulomas resembling papular rosacea; the initial belief was that this finding represented a rosacealike tuberculid eruption.5 However, this belief was questioned by Snapp,16 among others, who demonstrated near universal lack of reactivity to tuberculin among 20 of these patients in 1949; more recent evidence has substantiated these findings.17 Still, Snapp16 postulated that these rosacealike granulomatous lesions were distinct from classic rosacea because they lacked vascular symptoms and pustules and were recalcitrant to rosacea treatment modalities.