Psoriatic Alopecia in a Patient With Crohn Disease: An Uncommon Manifestation of Tumor Necrosis Factor α Inhibitors

Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitors are used to treat multiple inflammatory diseases including rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and psoriasis, among others. This family of medications can cause various side effects, some as common as injection-site reactions and others as rare as the paradoxical induction of psoriasiform skin lesions. Alopecic plaques recently have been described as an uncommon adverse effect of the TNF-α inhibitors adalimumab and infliximab. We present the case of a 12-year-old girl treated with adalimumab for Crohn disease who developed an alopecic crusted plaque on the scalp 6 months after increasing the dose of the medication. Biopsies, special stains, and sterile cultures yielded a diagnosis of psoriatic alopecia secondary to TNF-α inhibitor. A literature review for similar cases found 24 additional patients presenting with similar findings, of which only 6 were part of the pediatric population.

Practice Points

- Psoriatic alopecia is a rare nonscarring alopecia that can present as a complication of treatment with tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors.

- This finding commonly is seen in females undergoing treatment with infliximab or adalimumab, usually for Crohn disease.

- Histopathologic findings can show a psoriasiform-pattern, neutrophil-rich, inflammatory infiltrate involving hair follicles or a lichenoid pattern.

Comment

Psoriatic alopecia induced by a TNF-α inhibitor was first reported in 2007 in a 30-year-old woman with ankylosing spondylitis who was being treated with adalimumab.8 She had erythematous, scaly, alopecic plaques on the scalp and palmoplantar pustulosis. Findings on skin biopsy were compatible with psoriasis. The patient’s severe scalp psoriasis failed to respond to topical steroid treatment and adalimumab cessation. The extensive hair loss responded to cyclosporine 3 mg/kg daily.8

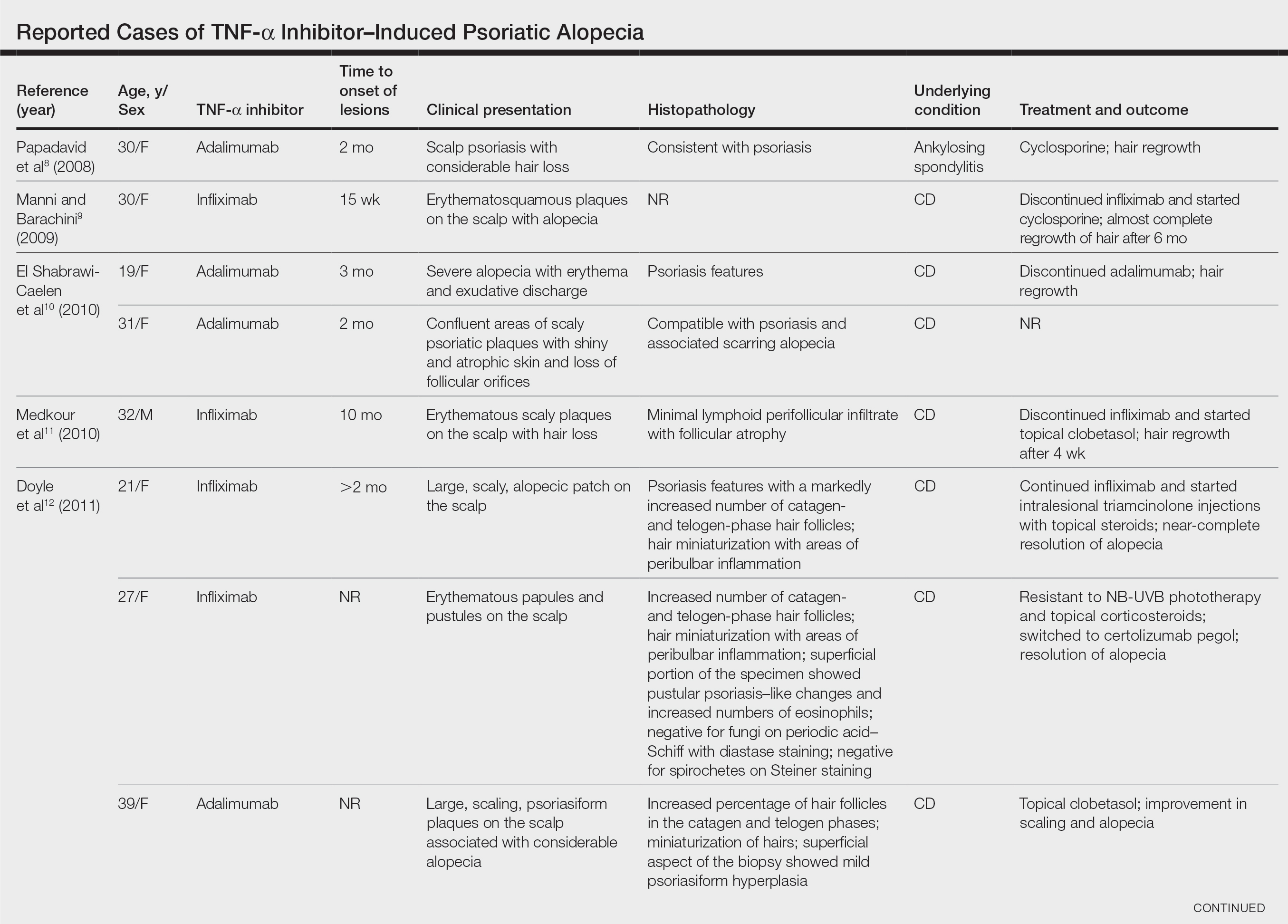

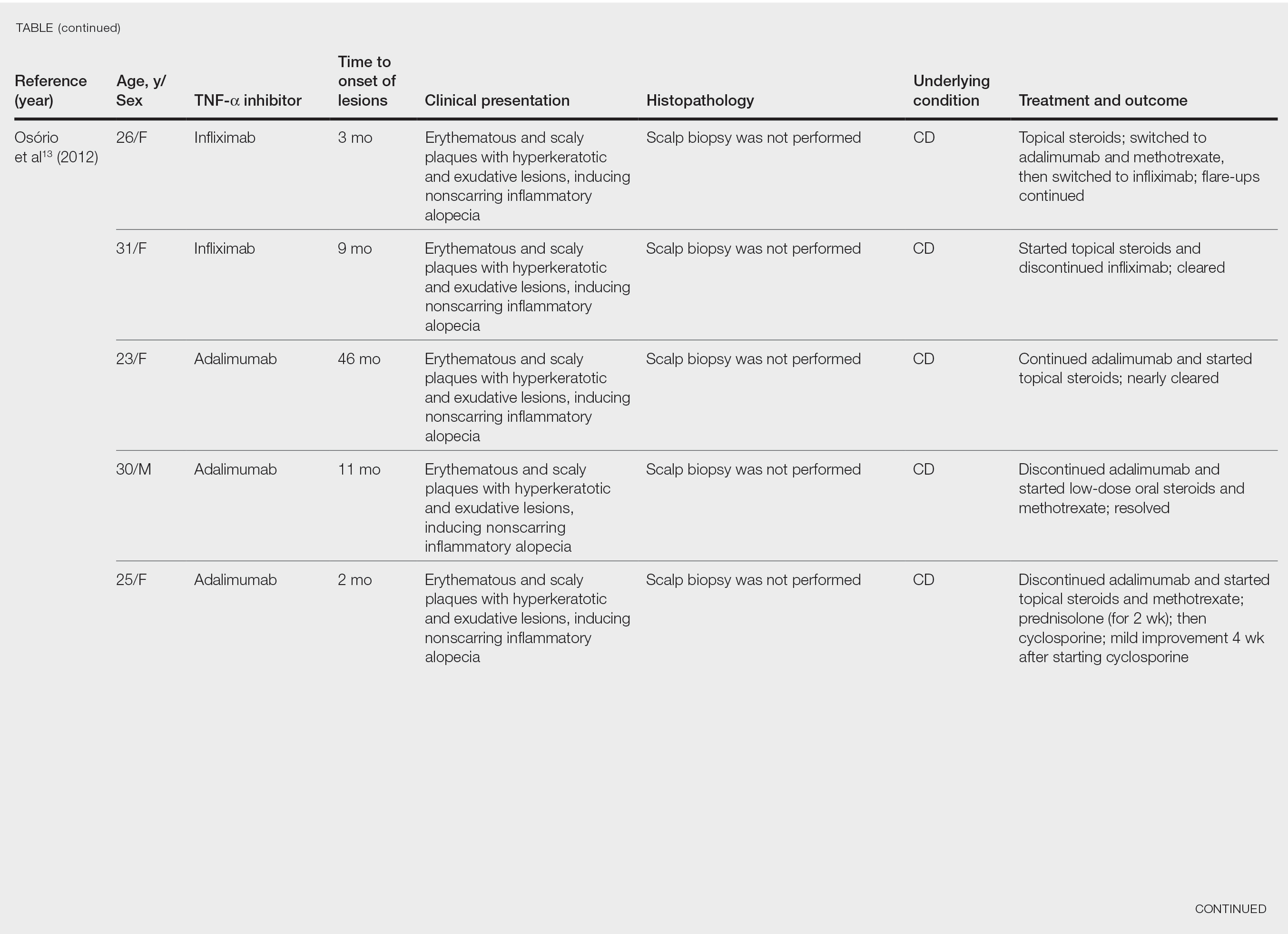

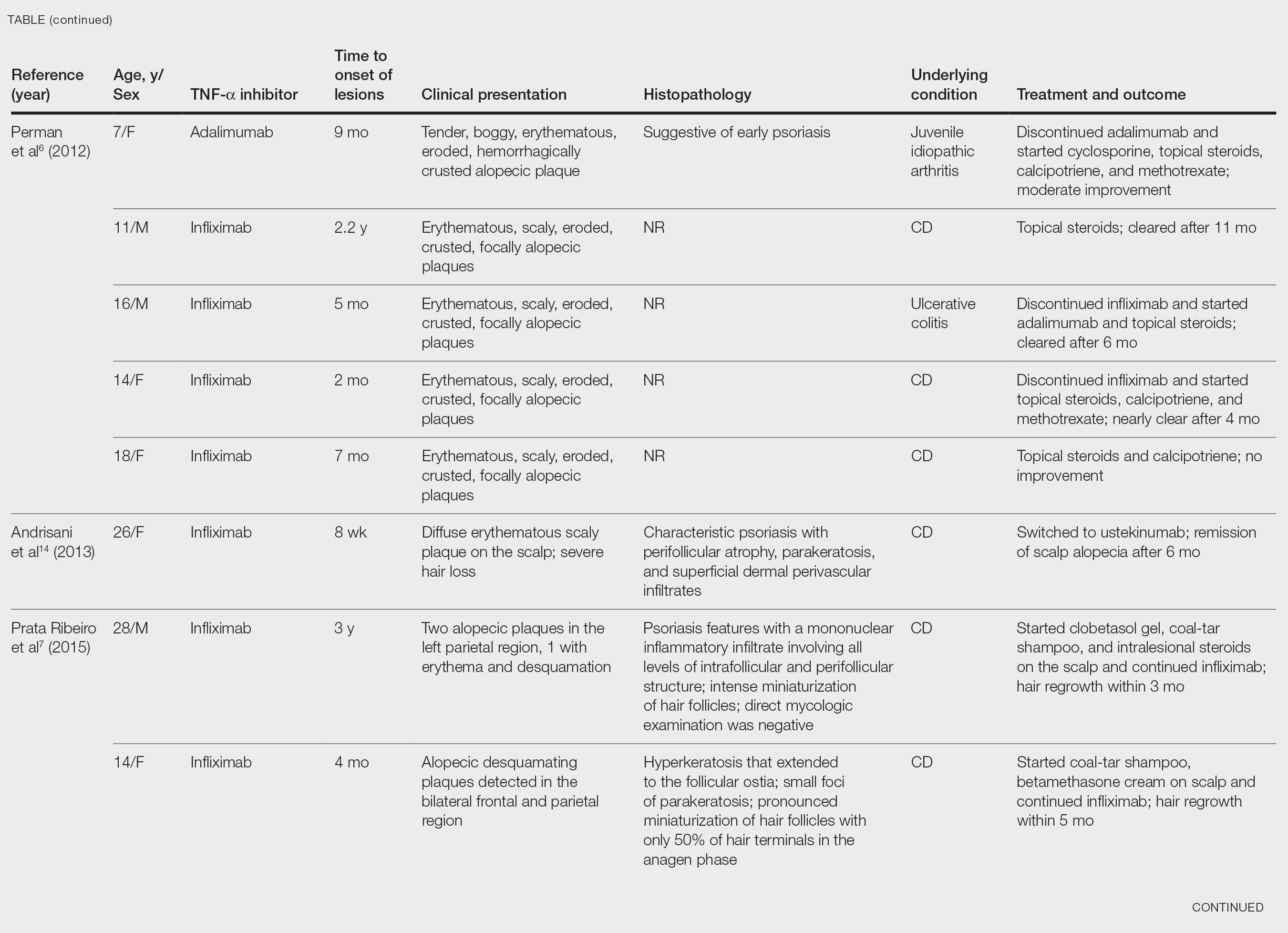

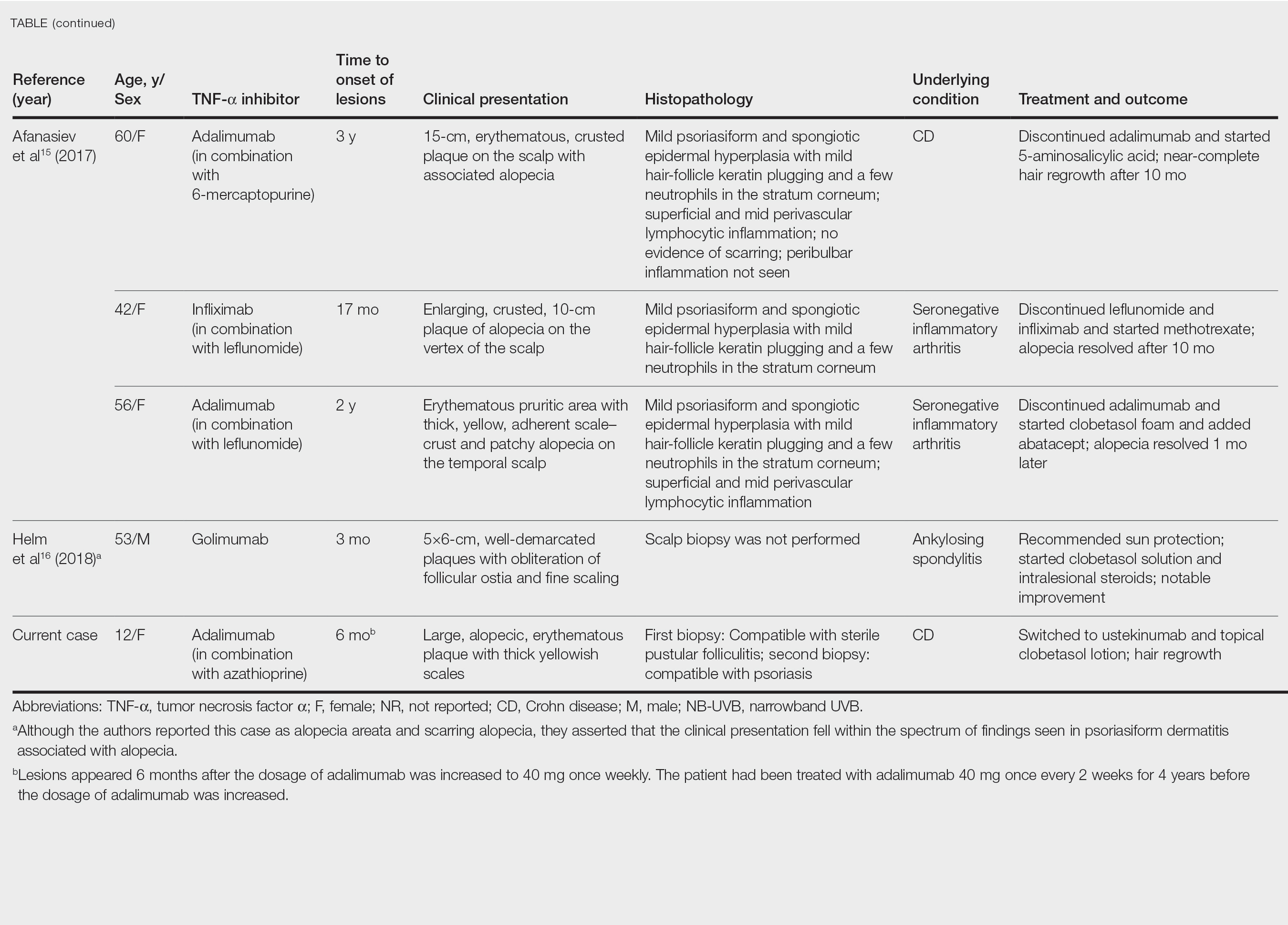

After conducting an extensive literature review, we found 26 cases of TNF-α–induced psoriatic alopecia, including the current case (Table).6-16 The mean age at diagnosis was 27.8 years (SD, 13.6 years; range, 7–60 years). The female-to-male ratio was 3.3:1. The most common underlying condition for which TNF-α inhibitors were prescribed was CD (77% [20/26]). Psoriatic alopecia most commonly was reported secondary to treatment with infliximab (54% [14/26]), followed by adalimumab (42% [11/26]). Golimumab was the causative drug in 1 (4%) case. We did not find reports of etanercept or certolizumab having induced this manifestation. The onset of the scalp lesions occurred 2 to 46 months after starting treatment with the causative medication.

Laga et al17 reported that TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriasis can have a variety of histopathologic findings, including typical findings of various stages of psoriasis, a lichenoid pattern mimicking remnants of lichen planus, and sterile pustular folliculitis. Our patient’s 2 scalp biopsies demonstrated results consistent with findings reported by Laga et al.17 In the first biopsy, findings were consistent with a dense neutrophilic infiltrate with negative sterile cultures and negative periodic acid–Schiff stain (sterile folliculitis), with crust and areas of parakeratosis. The second biopsy demonstrated psoriasiform hyperplasia, parakeratosis, and an absent granular layer, all typical features of psoriasis (Figure 2).

Including the current case, our review of the literature yielded 7 pediatric (ie, 0–18 years of age) cases of TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriatic alopecia. Of the 6 previously reported pediatric cases, 5 occurred after administration of infliximab.6,7

Similar to our case, TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriatic alopecia was reported in a 7-year-old girl who was treated with adalimumab for juvenile idiopathic arthritis.6 Nine months after starting treatment, that patient presented with a tender, erythematous, eroded, and crusted alopecic plaque along with scaly plaques on the scalp. Adalimumab was discontinued, and cyclosporine and topical steroids were started. Cyclosporine was then discontinued due to partial resolution of the psoriasis; the patient was started on abatacept, with persistence of the psoriasis and alopecia. The patient was then started on oral methotrexate 12.5 mg once weekly with moderate improvement and mild to moderate exacerbations.

Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced psoriasis may occur as a result of a cytokine imbalance. A TNF-α blockade leads to upregulation of interferon α (IFN-α) and TNF-α production by plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), usually in genetically susceptible people.6,7,9-15 The IFN-α induces maturation of myeloid dendritic cells (mDCs) responsible for increasing proinflammatory cytokines that contribute to psoriasis.11 Generation of TNF-α by pDCs leads to mature or activated dendritic cells derived from pDCs through autocrine TNF-α production and paracrine IFN-α production from immature mDCs.9 Once pDCs mature, they are incapable of producing IFN-α; TNF-α then inhibits IFN-α production by inducing pDC maturation.11 Overproduction of IFN-α during TNF-α inhibition induces expression of the chemokine receptor CXCR3 on T cells, which recruits T cells to the dermis. The T cells then produce TNF-α, causing psoriatic skin lesions.10,11,13,14

Although TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriatic alopecia is uncommon, the condition should be considered in female patients with underlying proinflammatory disease—CD in particular. Perman et al6 reported 5 cases of psoriatic alopecia in which 3 patients initially were treated with griseofulvin because of suspected tinea capitis.

Conditions with similar clinical findings should be ruled out before making a diagnosis of TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriatic alopecia. Although clinicopathologic correlation is essential for making the diagnosis, it is possible that the histologic findings will not be specific for psoriasis.17 It is important to be aware of this condition in patients being treated with a TNF-α inhibitor as early as 2 months to 4 years or longer after starting treatment.

Previously reported cases have demonstrated various treatment options that yielded improvement or resolution of TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriatic alopecia. These include either continuation or discontinuation of the TNF-α inhibitor combined with topical or intralesional steroids, methotrexate, or cyclosporine. Another option is to switch the TNF-α inhibitor to another biologic. Outcomes vary from patient to patient, making the physician’s clinical judgment crucial in deciding which treatment route to take. Our patient showed notable improvement when she was switched from adalimumab to ustekinumab as well as the combination of ustekinumab and clobetasol lotion 0.05%.

Conclusion

We recommend an individualized approach that provides patients with the safest and least invasive treatment option for TNF-α inhibitor–induced psoriatic alopecia. In most reported cases, the problem resolved with treatment, thereby classifying this form of alopecia as noncicatricial alopecia.