Laser Safety: The Need for Protocols

Lasers are being used in ever-expanding roles in dermatology. As our understanding of laser energy grew, the need for safety guidelines became apparent. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) published the first safety guidelines in 1984, which are updated on a regular basis. However, these are just guidelines, and their implementation is voluntary by the laser practitioner. In this article, we discuss the 4 regulatory entities for laser safety in the United States, laser principles in general, ocular hazards, laser-generated airborne contaminants (LGACs), fires, and unintended laser beam injuries. We also review the use of checklists in reducing adverse outcomes and the need for safety protocols for laser practitioners. We provide a modifiable checklist, which pertains specifically to lasers and can be customized to meet the needs of the individual laser practitioner.

Practice Points

- Laser therapy has evolved and expanded since its first cutaneous use in 1963.

- The 4 regulatory agencies for laser safety in the United States establish standards and guidelines, but implementation is voluntary.

- Ocular hazards, laser-generated airborne contaminants, fires, and unintended laser beam injuries constitute the main safety concerns.

- Safety protocols with a laser checklist can reduce adverse outcomes.

Laser-Generated Airborne Contaminants

Other hazards associated with laser use not directly related to the beam are laser-generated airborne contaminants (LGACs), including chemicals, viruses, bacteria, aerosolized blood products, and nanoparticles (<1 µm) known as ultrafine particles (UFPs). According to ANSI, electrosurgical devices and lasers generate the same smoke. The plume (surgical smoke) is known to contain as many as 60 chemicals, including but not limited to carbon monoxide, acrylonitrite, hydrocyanide, benzene, toluene, naphthalene, and formaldehyde. Several are known carcinogens, and others are environmental toxins.6,7

Smoke management is an important consideration for dermatologists and their patients and generally includes respiratory protection via masks and ventilation techniques. However, the practice is not universal, and oversight agencies such as OSHA and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) provide guidelines only; they do not enforce. As such, smoke management is voluntary and not widely practiced. In a 2014 survey of 997 dermatologic surgeons who were asked if smoke management is used in their practice, 77% of respondents indicated no smoke management was used.6

The Surgical Plume: Composition

A 2014 study from the University of California, San Diego Department of Dermatology analyzed surgical smoke.6 The researchers placed the smoke collection probe 16 to 18 inches above the electrocautery site, which approximates the location of the surgeon’s head during the procedure. Assessing smoke composition, they found high levels of carcinogens and irritants. Two compounds found in their assay—1,3-butadiene and benzene—also are found in secondhand cigarette smoke. However, the concentrations in the plume were 17-fold higher for 1,3-butadiene and 10-fold higher for benzene than those found in secondhand cigarette smoke. The risk from chronic, long-term exposure to these airborne contaminants is notable, as benzene (a known carcinogen as determined by the US Department of Health and Human Services) is known to cause leukemia. For example, a busy Mohs surgeon can reach the equivalent of as many as 50 hours of continuous smoke exposure over the course of a year.6

The Surgical Plume: Particle Concentration

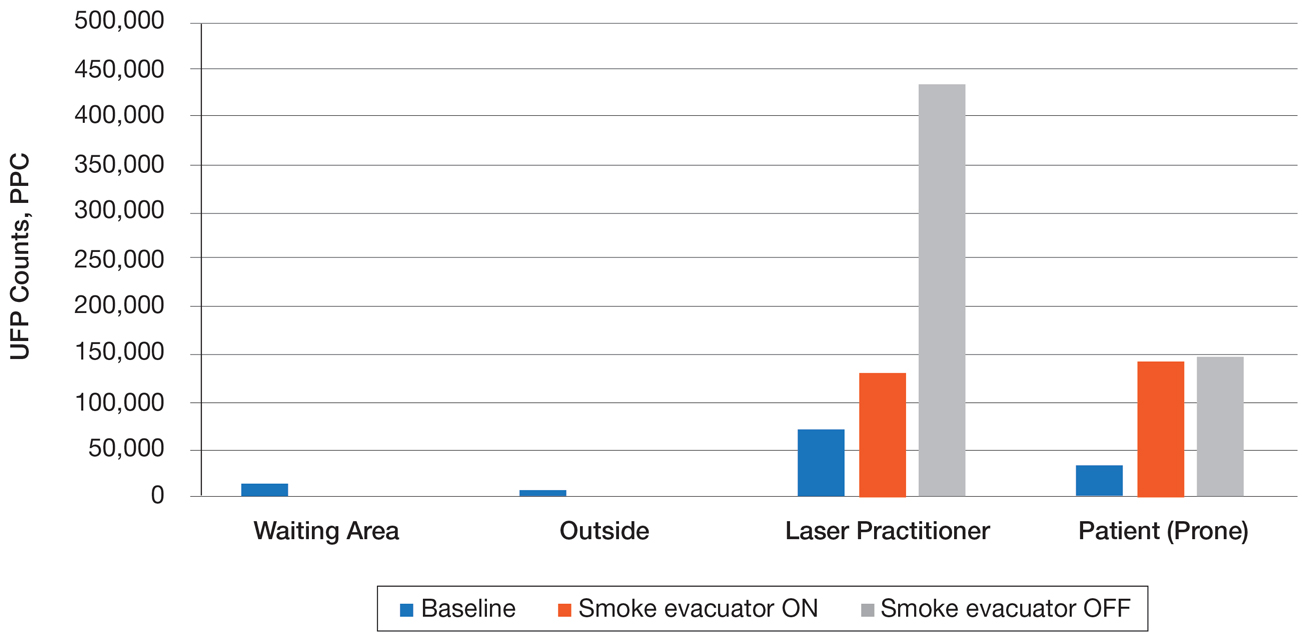

Ultrafine particles can bypass conventional filtering systems (surgical masks and N95 respirators) because of their extremely small size, which allows them to pass further into the lungs and all the way to the alveolar spaces. Geographic regions with high UFPs have been shown to have higher overall mortality rates, as well as higher rates of reactive airway disease, cardiovascular disease, and lung cancer. A 2016 study by Chuang et al7 published in JAMA Dermatology looked at the UFPs in the surgical plume from laser hair removal (LHR) procedures. The plume of LHR has a distinct odor and easily discernible particulates. The investigators measured the UFPs at the level of the laser practitioner and the patient’s face during LHR with a smoke evacuator turned on and again with it turned off for 30 seconds, and then compared them to UFPs measured in the treatment room, the waiting room, and outside the building. There were substantial increases in UFPs from the LHR procedure, especially for the laser practitioner, when the smoke evacuator was off. The ambient baseline particle count, as measured in the clinic waiting area, began at 15,300 particles per cubic centimeter (PPC), and once the LHR procedure began (smoke evacuator on), there was a greater than 8-fold PPC increase above baseline (15,300 PPC to 129,376 PPC) in UFPs measured for the laser practitioner. Importantly, during LHR when the smoke evacuator was turned off for 30 seconds, there was a more than 28-fold increase (15,300 PPC to 435,888 PPC) over baseline to the practitioner (Figure).7

The Surgical Plume: Viruses, Bacteria, and Aerosolized Blood Products

Viruses and bacteria are thought to be transmissible via the plume, and proviral human immunodeficiency virus DNA has been found in the plume as well as evacuator equipment used to reduce plume exposure.8 A study from 1988 found that CO2 laser users treating verrucae had human papillomavirus in the laser plume.9 A comparison study of CO2 laser users treating verrucae had an increased incidence of nasopharyngeal human papillomavirus infection when compared to a control group, and the plume also contained aerosolized blood.10 The American National Standards Institute, OSHA, and NIOSH all agree that LGAC control from lasers is necessary through respiratory protection and ventilation, but none of these organizations provides specific equipment recommendations. The American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery has published a position statement on laser plume.11

The Surgical Plume: Smoke Management

Many virus particles and UFPs are less than 0.1 µm in size. It is important to note that neither surgical masks nor high-filtration masks, such as the N95 respirator, filter particles smaller than 0.1 µm. The first line of defense in smoke management is the local exhaust ventilation (LEV) system, which includes wall suction and/or a smoke evacuator. The smoke evacuator is considered the more important of the two. General filtration, such as wall suction, is a low-flow system and is really used for liquids. It can be used as a supplement to the smoke evacuator to control small amounts of plume if fitted with an in-line filter. There are 2 types of LEV filters: ultralow particulate air filters filter particles larger than 0.1

Of utmost importance when using a smoke evacuator system is suction tip placement. Placing the suction tip 1 cm from the tissue damage site has been shown to be 98.6% effective at removing laser plume. If moved to 2 cm, effectiveness decreases to less than 50%.11 Proper management recommendations based on current evidence suggest that use of a smoke evacuator and an approved fit-tested N95 respirator might provide maximum protection.6 In addition to plume exposure, tissue splatter can occur, especially during ablative (CO2) and tattoo laser therapy, which should prompt consideration of a face shield.11 There are several vendors and models available online, and a simple Internet search for surgical tissue splatter face shields will provide multiple options.