Cutaneous Nocardiosis in an Immunocompromised Patient

We describe a case of a 79-year-old man with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who presented with ataxia; falls; vision loss; and numerous mobile erythematous nodules on the chin, neck, scalp, and trunk. Computed tomography of the head and chest revealed cavitary lesions in the brain and lungs. Clinically, the skin nodules were believed to represent an infectious process. Two punch biopsies were obtained, which revealed an unremarkable epidermis with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with abscess formation in the dermis. Gram stain highlighted gram-positive branching bacterial organisms. Similar organisms were identified in a bronchoalveolar lavage specimen. Cultures from skin and blood were positive for Nocardia. Our case serves as a reminder to clinicians and pathologists to keep a broad differential diagnosis when dealing with infectious diseases in immunocompromised patients.

Practice Points

- Clinicians should consider a broad differential when dealing with infectious diseases in immunocompromised patients.

- Primary cutaneous nocardiosis classically presents as tumors or nodules with a sporotrichoid pattern along the lymphatics. Vesiculopustules and abscesses are seen in disseminated disease, which usually involves the skin, lungs, and/or central nervous system.

- Nocardia species are characteristically gram-positive, thin rods that form beaded, right-angle branching filaments.

- When nocardiosis is in the differential, special care should be taken, as organisms can be gram variable or only partially acid fast. Gram, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, and acid-fast staining may be essential to making the diagnosis.

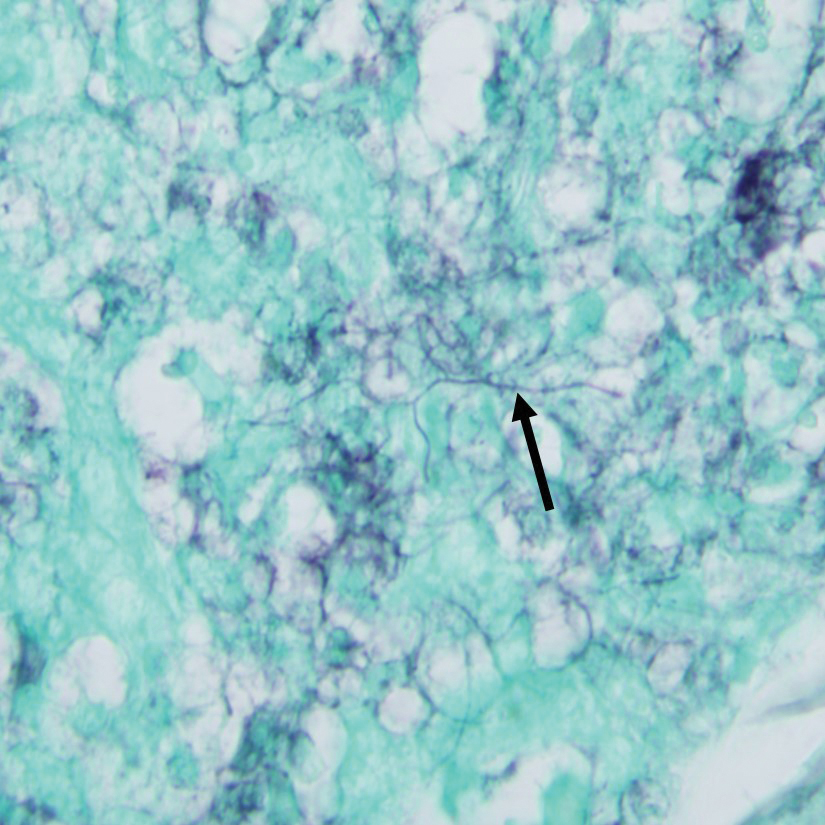

Gram stain revealed gram-variable, branching, bacterial organisms morphologically consistent with Nocardia. Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid–Schiff stains also highlighted the bacterial organisms (Figure 5). An auramine-O stain was negative for acid-fast microorganisms. After 3 days on a blood agar plate, cultures of a specimen of the chin nodule grew branching filamentous bacterial organisms consistent with Nocardia.

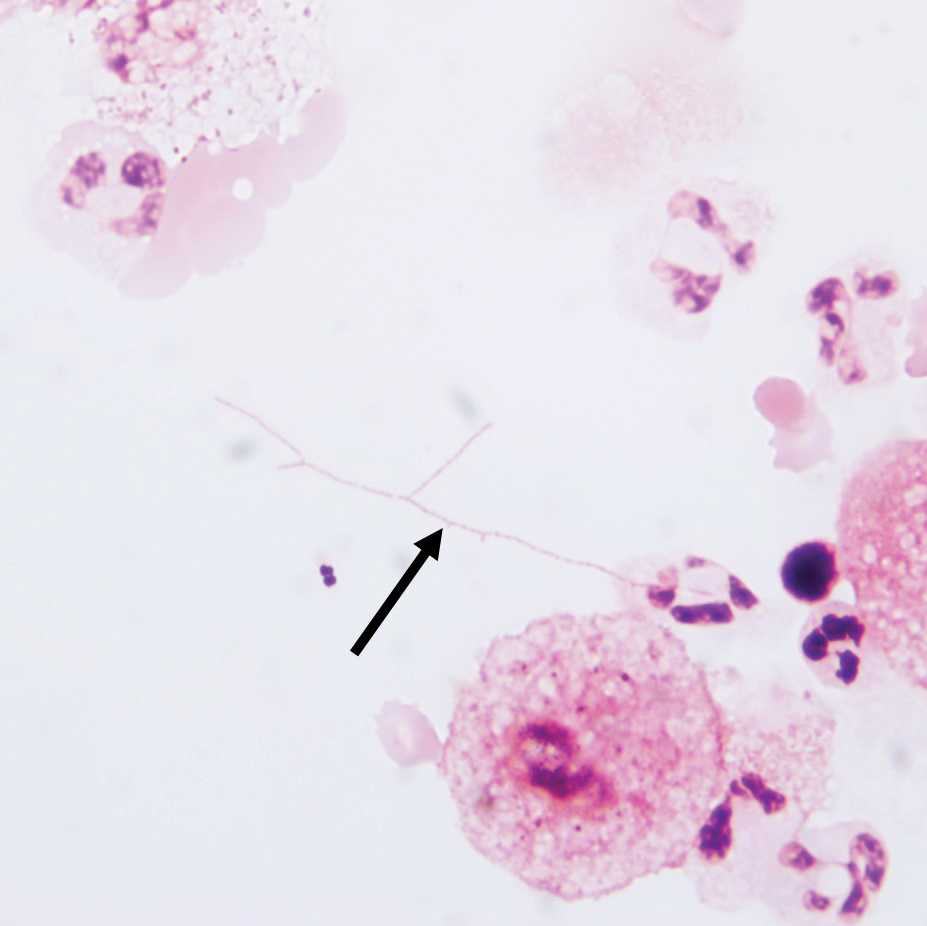

Additionally, morphologically similar microorganisms were identified on a specimen of bronchoalveolar lavage (Figure 6). Blood cultures also returned positive for Nocardia. The specimen was sent to the South Dakota Public Health Laboratory (Pierre, South Dakota), which identified the organism as Nocardia asteroides. Given the findings in skin and the lungs, it was thought that the ring-enhancing lesion in the brain was most likely the result of Nocardia infection.

,Antibiotic therapy was switched to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. The patient’s mental status deteriorated; vital signs became unstable. He was transferred to the intensive care unit and was found to be hyponatremic, most likely a result of the brain lesion causing the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion. Mental status and clinical condition continued to deteriorate; the patient and his family decided to stop all aggressive care and move to a comfort-only approach. He was transferred to a hospice facility and died shortly thereafter.

Comment

Presentation and Diagnosis

Nocardiosis is an infrequently encountered opportunistic infection that typically targets skin, lungs, and the central nervous system (CNS). Nocardia species characteristically are gram-positive, thin rods that form beaded, right-angle, branching filaments.1 More than 50 Nocardia species have been clinically isolated.2

Definitive diagnosis requires culture. Nocardia grows well on nonselective media, such as blood or Löwenstein-Jensen agar; growth can be enhanced with 10% CO2. Growth can be slow, however, and takes from 48 hours to several weeks. Nocardia typically grows as buff or pigmented, waxy, cerebriform colonies at 3 to 5 days’ incubation.1

Cause of Infection

Nocardia species are commonly found in the environment—soil, plant matter, water, and decomposing organic material—as well as in the gastrointestinal tract and skin of animals. Infection has been reported in cattle, dogs, horses, swine, birds, cats, foxes, and a few other animals.2 A history of exposure, such as gardening or handling animals, should increase suspicion of Nocardia.3 Although infection is classically thought to affect immunocompromised patients, there are case reports of immunocompetent individuals developing disseminated infection.4-7 However, infected immunocompetent individuals typically have localized cutaneous infection, which often includes cellulitis, abscesses, or sporotrichoid patterns.2 Cutaneous infections typically are the result of direct inoculation of the skin through a penetrating injury.8

Disseminated nocardiosis can be caused by numerous species and generally is the result of primary pulmonary infection.9 In these cases, skin disease is present in approximately 10% of patients. Disseminated infection from cutaneous nocardiosis is uncommon; when it does occur, the most common site of dissemination is the CNS, resulting in abscess or cerebritis.10 Therefore, CNS involvement should always be ruled out on diagnosis in immunocompromised patients, even if neurologic symptoms are absent.9 Nearly 80% of patients with disseminated disease are, in fact, immunocompromised.8