Energy-Based Devices for Actinic Keratosis Field Therapy

Cutaneous field cancerization arises due to UV-induced carcinogenesis of a “field” of subclinically transformed skin and actinic keratoses (AKs) with a tendency to progress and recur. Commonly used treatment methods for multiple AKs include imiquimod, fluorouracil, ingenol mebutate, and photodynamic therapy; however, new options in field-directed therapy with superior efficacy, cosmesis, and convenience may appeal to patients. Ablative and nonablative lasers may fulfill these advantages and have been investigated as monotherapies and combination therapies for field cancerization. In this article, a review of the literature on various laser modalities with a focus on efficacy is provided.

Practice Points

- Ablative fractional laser therapy in combination with photodynamic therapy has demonstrated increased efficacy in treating field actinic keratoses (AKs) for up to 12 months of follow-up over either modality alone.

- Ablative and nonablative lasers as monotherapy in treating field AKs require further studies with larger sample sizes to determine efficacy and safety.

Nonablative Lasers

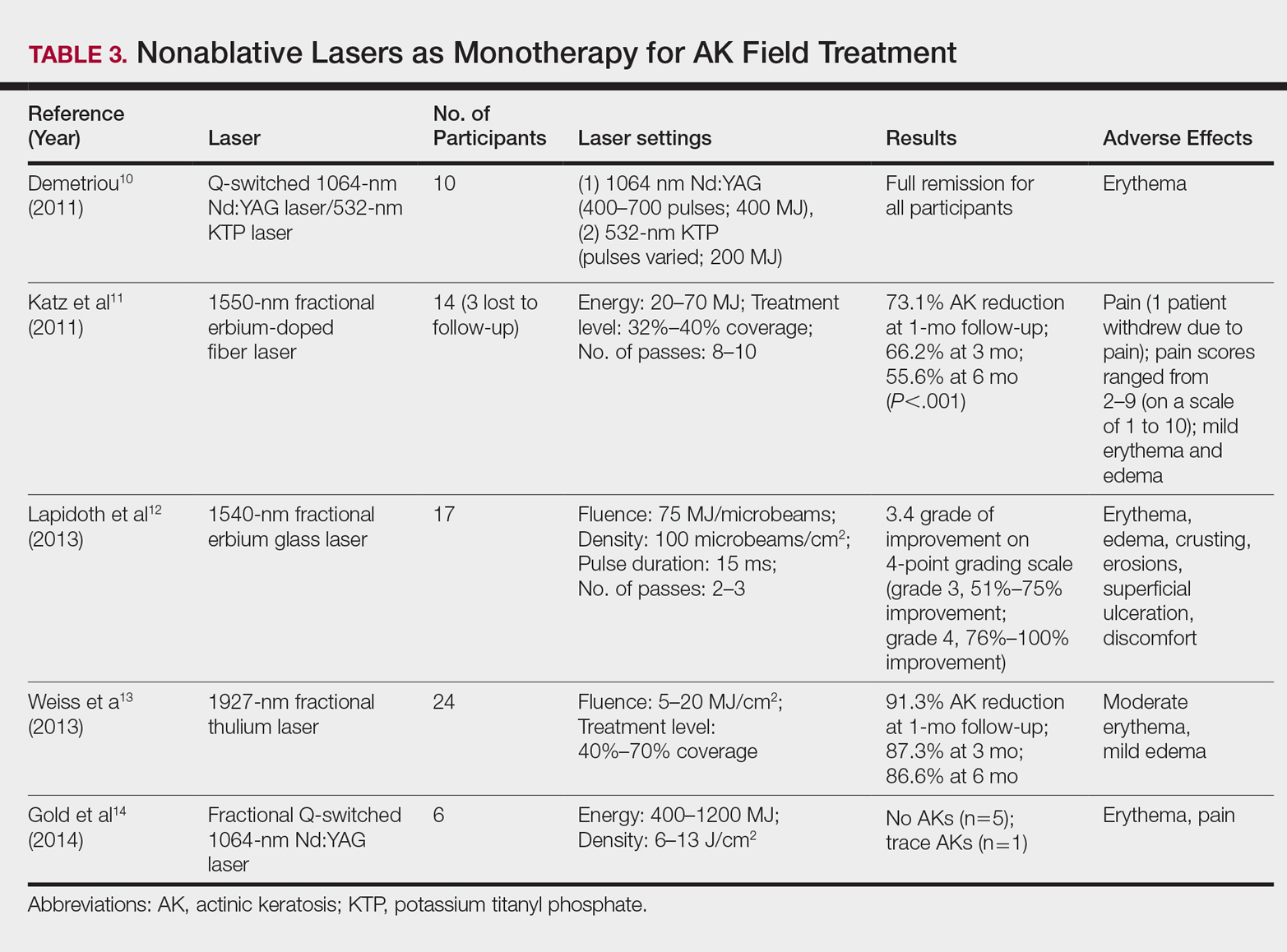

By heating the dermis to induce neogenesis without destruction, nonablative lasers offer superior healing times compared to their ablative counterparts. Multiple treatments with nonablative lasers may be necessary for maximal effect. Four nonablative laser devices have demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of multiple AKs10-14: (1) the Q-switched 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser, with or without a 532-nm potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) laser; (2) the 1540-nm fractional erbium glass laser; (3) the 1550-nm fractional erbium-doped fiber laser; and (4) the 1927-nm fractional thulium laser (Table 3).

In a proof-of-concept study of the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser with the 532-nm KTP laser, 1 treatment session induced full remission of AKs in 10 patients at follow-up day 20, although the investigator did not grade improvement on a numerical scale.10 In a study of the fractional Q-switched 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser alone, 6 patients with trace or mild AKs received 4 treatment sessions at approximately 2-week intervals.14 All but 1 patient (who had trace AKs) had no AKs at 3-month follow-up.

The efficacy of the 1540-nm fractional erbium glass laser was examined in 17 participants with investigator-rated moderate-to-severe AK involvement of the scalp and face.12 Participants were given 2 or 3 treatment sessions at 3- to 4-week intervals and were graded by blinded dermatologists on a quartile scale of 0 (no improvement), 1 (1%–25% improvement), 2 (26%–50% improvement), 3 (51%–75% improvement), or 4 (76%–100% improvement). At 3 months posttreatment, the average grade of improvement was 3.4.12

The 1550-nm fractional erbium-doped fiber laser was tested in 14 men with multiple facial AKs (range, 9–44 AKs [mean, 22.1 AKs]).11 Participants received 5 treatment sessions at 2- to 4-week intervals, with majority energies used at 70 MJ and treatment level 11. The mean AK count was reduced significantly by 73.1%, 66.2%, and 55.6% at 1-, 3-, and 6-month follow-up, respectively (P<.001).11

The 1927-nm fractional thulium laser showed promising results in 24 participants with facial AKs.13 Participants received up to 4 treatment sessions at intervals from 2 to 6 weeks at the investigators’ discretion. At baseline, patients had an average of 14.04 facial AKs. At 1-, 3-, and 6-month follow-up, participants exhibited 91.3%, 87.3%, and 86.6% reduction in AK counts, respectively. The mean AK count at 3-month follow-up was 1.88.13

Due to limited sample sizes and/or lack of quantifiable results and controls in these studies, more studies are needed to fully elucidate the role of nonablative lasers in the treatment of AK.

Future Directions

Iontophoresis involves the noninvasive induction of an electrical current to facilitate ion movement through the skin and may be a novel method to boost the efficacy of current field therapies. In the first known study of its kisnd, iontophoresis-assisted AFXL-PDT was found to be noninferior to conventional AFXL-PDT15; however, additional studies demonstrating its superiority are needed before more widespread clinical use is considered.

Pretreatment with AFXL prior to topical field-directed therapies also has been proposed.16 In a case series of 13 patients, combination therapy with AFXL and ingenol mebutate was shown to be superior to ingenol mebutate alone (AK clearance rate, 89.2% vs 72.1%, respectively; P<.001).16 Randomized studies with longer follow-up time are needed.

Conclusion

Ablative and nonablative laser systems have yielded limited data about their potential as monotherapies for treatment of multiple AKs and are unlikely to replace topical agents and PDT as a first-line modality in field-directed treatment at this time. More studies with a larger number of participants and long-term follow-up are needed for further clarification of efficacy, safety, and clinical feasibility. Nevertheless, fractional ablative lasers in combination with PDT have shown robust efficacy and a favorable safety profile for treatment of multiple AKs.6-9 Further, this combination therapy exhibited a superior clearance rate and lower lesion recurrence in organ transplant recipients—a demographic that classically is difficult to treat.6-9

With continued rapid evolution of laser systems and more widespread use in dermatology, monotherapy and combination therapy may offer a dynamic new option in field cancerization that can decrease disease burden and treatment frequency.