Ulcerative Sarcoidosis: A Prototypical Presentation and Review

Although rare, ulcerative sarcoidosis is an acknowledged morphologic variant of cutaneous sarcoidosis encountered in both the United States and worldwide, particularly in patients with skin of color. Herein, we present a patient with prototypical ulcerative sarcoidosis to highlight this unusual presentation of a relatively rare cutaneous condition. We also review 34 additional cases drawn from the English-language literature to define historical presentation, associated findings, treatments, and outcomes.

Practice Points

- Sarcoidosis can present as a primary ulcerative disease.

- Suspect ulcerative sarcoidosis when ulcerations are seen on the leg.

- Systemic corticosteroids may be the most effective treatment of ulcerative sarcoidosis.

Comment

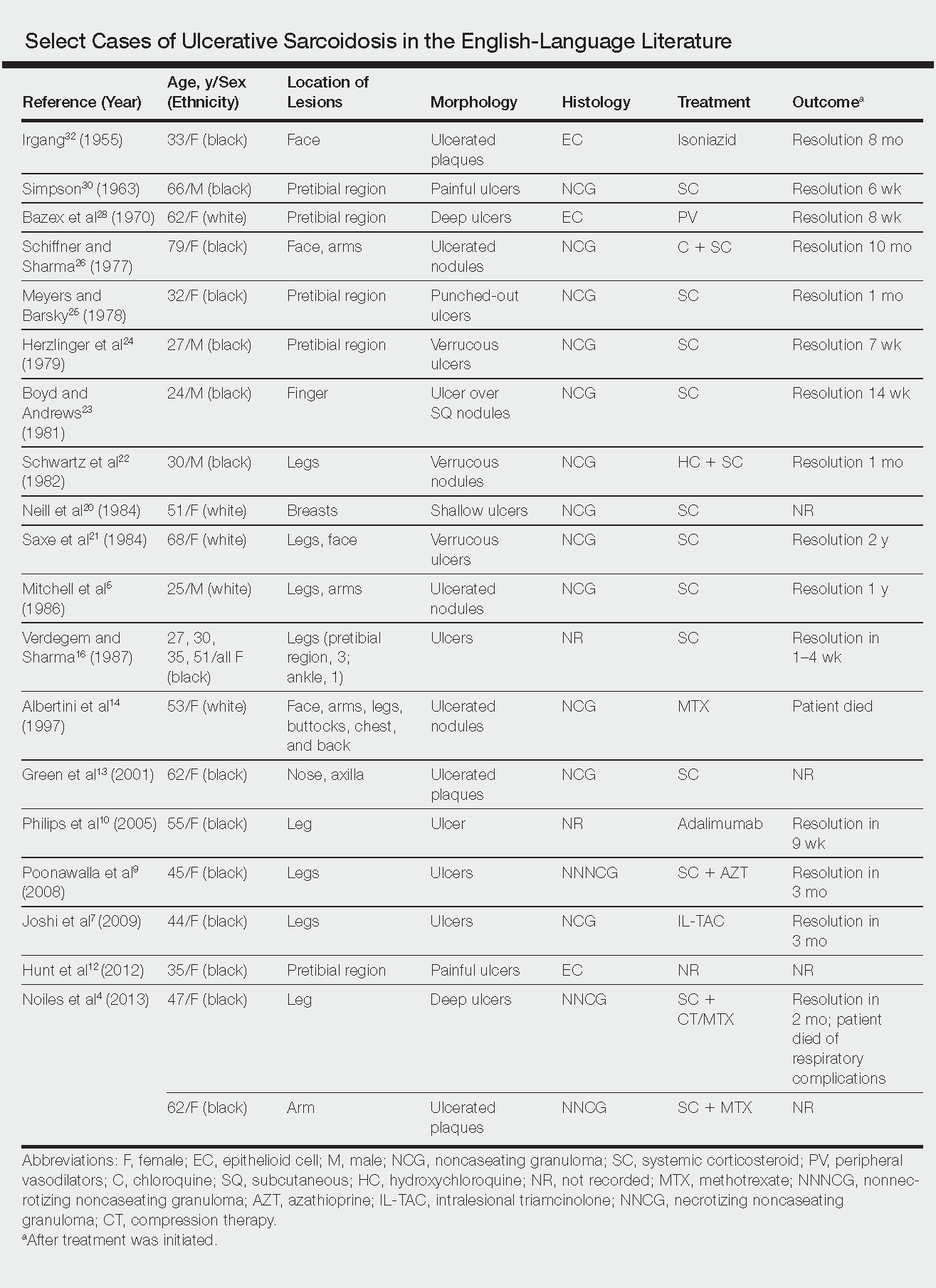

Ulcerative sarcoidosis is rare, seen worldwide in only 5% of patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis.33 However, cases have been encountered worldwide, with reports emanating from Japan, China, Germany, France, and Russia, among others.6,34-55 We reviewed 34 cases from the English-language literature based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term ulcerative sarcoid and examined patient demographics, clinical presentation, histological findings, treatment type, and outcome. Key references are presented in the Table. Disease prevalence previously has been estimated as being 3-times more common in women than men1; in our literature review, we found a female to male ratio of 3.25 to 1. Additionally, ulcerative sarcoidosis is reported to be twice as common in black versus white individuals.33 In our literature review, when race was reported, 66% (21/32) of patients were black. Disease prevalence has been reported to peak at 20 to 40 years of age.3 In this review, the average age of presentation was 45 years (age range, 24–79 years).

Ulceration may arise de novo but more commonly arises in preexisting scars or cutaneous lesions. There are 2 distinct patterns seen in ulcerative sarcoidosis.4 The first is characterized by ulceration within necrotic yellow plaques.2 The second pattern is characterized by violaceous nodules arising in an annular confluent pattern that eventually ulcerate.4 This presentation commonly mimics or may be mimicked by multiple disease states, including sporotrichosis, tuberculosis, stasis dermatitis with venous ulceration, and even metastatic breast cancer.7,46,55,56 Regardless of presentation, the legs are the most common location of ulcer formation.1,33 In our review, 85% (29/34) of cases presented with involvement of the legs, including our own case. Other locations of ulcer formation have included the face, arms, trunk, and genital area.

On histologic examination of ulcerative sarcoidosis, epithelioid granulomas composed of multinucleated giant cells, histiocytes, and scant numbers of lymphocytes are present.1,3 These formations are the noncaseating granulomas typical of sarcoidosis (Table). All of the cases in our review of the literature were described as either a collection of epithelioid granulomas with giant cell formation or noncaseating granulomas. There also have been reports of atypical features including necrotizing granulomas and granulomatous vasculitis.4,8,9,50 The histologic differential diagnosis in this case also would primarily include an infectious granulomatous process and less so an id reaction, rosacea, a paraneoplastic phenomenon, foreign body granulomas, and metastatic Crohn disease. The presence of ulceration, the large number of lesions, and the anatomic distribution help rule out most of these alternate diagnostic considerations. Diligent extensive workup was done in our patient to insure it was not an infection.

,

The goals of treatment include symptomatic relief, improvement in objective parameters of disease activity, and prevention of disease progression and subsequent disability.33,57 Fortunately, the majority of sarcoidosis patients with cutaneous symptoms achieve full recovery within months to years.33 Our literature review indicated that 81% (22/27) of patients with ulcerative lesions experienced full resolution within 1 year of treatment. Of those that did not (19% [5/27]), the patients were either lost to follow-up or died from other complications of sarcoidosis.

The widely accepted standard therapy for cutaneous sarcoidosis includes topical, intralesional, and systemic corticosteroids; antimalarials; and methotrexate.33,57 Steroids and methotrexate act by suppressing granuloma formation, while antimalarials prevent antigen presentation (presumably part of the pathogenesis).33 For mild to moderate disease, topical and intralesional steroids may be all that is necessary.33,57 Systemic steroids are used for disfiguring, destructive, and widespread lesions that have been refractory to local and other systemic therapies.33,57 Steroids are tapered gradually depending on the patient’s response, as it is common for patients to relapse below a certain dose.33,57 Antimalarials (chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine) and methotrexate are considered adjunct treatments for patients who are either steroid unresponsive or who are unable to tolerate corticosteroid treatment due to adverse events.33,57

Standard therapy is complicated by the side effects of treatment. Use of corticosteroids may lead to gastrointestinal tract upset, increased appetite, mood disturbances, impaired wound healing, hyperglycemia, hypertension, cushingoid features, and acne.57 Antimalarials can cause nausea, anorexia, and agranulocytosis, and chloroquine therapy in particular can lead to blurred vision, corneal deposits, and central retinopathy.33,57 Methotrexate is associated with hematologic, gastrointestinal tract, pulmonary, and hepatic toxicities well known to most practitioners.

Because of the variable clinical response of patients to standard therapy and their associated toxicities, other treatment options have been used including pentoxifylline, tetracyclines, isotretinoin, leflunomide, thalidomide, infliximab, adalimumab, allopurinol, and the pulsed dye or CO2 laser.10,33,57 In nonhealing ulcers, split-thickness grafting and a bilayered bioengineered skin substitute have been used with good results in conjunction with ongoing systemic therapy.11,47 Additionally, nanoparticle silver burn paste has been used successfully, with resolution of ulcers within 2 weeks in the Chinese literature.53

All of these treatment recommendations are based on historically accepted modalities. Controlled trials with longitudinal follow-up are needed to provide justification for the current standard of care.34