Metastatic Crohn Disease: A Review of Dermatologic Manifestations and Treatment

It is estimated that almost half of patients affected with Crohn disease (CD) experience a dermatologic manifestation of the condition. Metastatic CD (MCD) is a rare dermatologic entity, with as few as 100 cases reported in the literature. As such, MCD presents a clinical dilemma in diagnosis and management. The etiology of MCD is not well defined; however, prevailing theories agree that the underlying mechanism is an immunologic response to gut antigens. Diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion and usually is made by exclusion of other processes. Treatment success has been reported with the use of antibiotics, immunosuppressants, and sometimes surgical treatment. We review the etiology/epidemiology, diagnostic criteria, and treatment of this uncommon condition.

Practice Points

- Almost half of patients with Crohn disease develop a dermatologic manifestation of the disease.

- The etiology of metastatic Crohn disease is unknown and diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion with exclusion of other processes.

Pathophysiology

The etiology of MCD has not been well defined. One proposed mechanism of the distal tissue involvement of MCD is through passage of antigens to the skin with subsequent granulomatous response at the level of the dermis.10 Another proposed mechanism suggests antibody sensitization to gut antigens, possibly bacterial antigens, that then coincidentally cross-react with analogous skin antigens.8,14 Burgdorf11 supported this notion in a 1981 report in which it was suggested that the granulomatous reaction was related to deposition of immune complexes in the skin. Slater et al15 and Tatnall et al16 offered a variation of Burgdorf's notion, suggesting that it was sensitized T cells to circulating antigens that were the initiators of granuloma formation in the periphery.

An examination of MCD tissue in 1990 by Shum and Guenther17 under electron microscopy and immunofluorescence provided evidence against prior studies that purported to have identified immune complexes as the causative agents of MCD. In this study, the authors found no evidence of immune complexes in the dermis of MCD lesions. In addition, an attempt to react serum antibodies of a patient with MCD, which were postulated to have IgG, IgM, and IgA antibodies to specific gut antigens, yielded no response when reacted with the tongue, ileum, and colon tissue from a rat. As a culminant finding, the authors also noted MCD dermis tissue with granulomas without vasculitis, suggesting a T-cell mediated type IV hypersensitivity response with a secondary vasculitis from T-cell origin lymphokines and T-cell mediated monocyte activation.17

Research implicating other immunologic entities involved in the pathophysiology of CD such as β-2 integrin,18 CD14+ monocytes,19 and the role of the DNA repair gene MLH1 (mutL homolog 1)20 have been considered but without a clearly definitive role in the manifestations of MCD.

,The utility of metronidazole in the treatment of MCD has been suggested as evidence that certain bacteria in the gut may either serve as the causative antigen or may induce its formation21; however, the causative antigen has yet to be identified, and whether it travels distally to the skin or merely resembles a similar antigen normally present in the dermis has not yet been determined. Some research has used in situ polymerase chain reaction techniques to attempt to detect similar microbial pathogens in both the vasculature of active bowel lesions and in the skin, but to date, bacterial RNA noted to be present in the gut vasculature adjacent to CD lesions has not been detected in skin lesions.22

Diagnosis

Physical Findings

Overall, it is estimated that roughly 56% of all MCD cases affect the external genitalia.23 The classic appearance of MCD includes well-demarcated ulcerations in the areas of intertriginous skin folds with or without diffuse edema and tenderness to palpation.23 Although MCD has been historically noted as having a predilection for moist skin folds, there are numerous case reports of MCD all over the body, including the face,7,24-29 retroauricular areas,30 arms and legs,16,17,31-34 lower abdomen,3,5 under the breasts,1 perineum,35 external genitalia,1,9,36-40 and even the lungs41 and bladder.42

As a dermatologic disease, MCD has been referred to as yet another great imitator, both on the macroscopic and microscopic levels.8 As such, more common causes of genital edema should be considered first and investigated based on the patient's history, physical examination, skin biopsy, lymphangiogram, ultrasound, and cystogram.43 Ultrasonography and color Doppler sonography have been shown to be helpful in patients with genital involvement. This modality can evaluate not only the presence of normal testes but also intratesticular and scrotal wall fluid, especially when the physical examination reveals swelling that makes testicle palpation more difficult.6 Clinically, the correct diagnosis of MCD often is made through suspicion of inflammatory bowel disease based on classic symptoms and/or physical findings including abdominal pain, weight loss, bloody stool, diarrhea, perianal skin tags, and anal fissures or fistulas. Any of these GI findings should prompt an intestinal biopsy to rule out any histologic evidence of CD.

Metastatic CD affecting the vulva often presents with vulvar pain and pruritus and may clinically mimic a more benign disease such as balanitis plasmacellularis, also referred to as Zoon vulvitis.23 Similar to MCD on any given body surface, there is dramatic variation in the macroscopic presentation of vulvar MCD, with physical examination findings ranging from bilateral diffuse, edematous, deeply macerated, red, ulcerated lesions over the vulva with lymphadenopathy to findings of bilateral vulvar pain with yellow drainage from the labia majora.23 There have been cases of vulvar MCD that include exquisite vulvar pain but without structural abnormalities including normal uterus, cervix, adnexa, rectovaginal septum, and rectum. In these more nebulous cases of vulvar MCD, the diagnosis often is discovered incidentally when nonspecific diagnostic imaging suggests underlying CD.23

Beyond the case-by-case variations on physical examination, the great difficulty in diagnosis, particularly in children, occurs in the absence of any GI symptoms and therefore no logical consideration of underlying CD. Consequently, there have been cases of children presenting with irritation of the vulva who were eventually diagnosed with MCD only after erroneous treatment of contact dermatitis, candidiasis, and even consideration of sexual abuse.37 Because it is so rare and obscure among practicing clinicians, the diagnosis of MCD often is considered only after irritation or swelling of the external genitalia has not responded to standard therapies. If and when the diagnosis of MCD is considered in children, it has been suggested to screen patients for anorectal stricture, as case studies have found the condition to be relatively common in this subpopulation.44

In the less common case of adults with genitourinary symptoms that suggest possible MCD, the differential diagnosis for penile or vaginal ulcers should include contact and irritant dermatitis, chronic infectious lesions (eg, hidradenitis suppurativa, actinomycosis, tuberculosis),45 sexually transmitted ulcerative diseases (eg, chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum, herpes genitalia, granuloma inguinale),46 drug reactions, and even extramammary Paget disease.47

Histologic Findings

Because MCD has so much macroscopic variation and can present anywhere on the surface of the body, formal diagnosis relies on microscopy. As an added measure of difficulty in diagnosis, one random biopsy of a suspicious segment of tissue may not contain the expected histologic findings; therefore, clinical suspicion may warrant a second biopsy.10 There have been reported cases of an adult patient without history of CD presenting with a lesion that resembled a more common pathology, such as a genital wart, and the correct diagnosis of MCD with pseudocondylomatous morphology was made only after intestinal manifestations prompted the clinician to consider such an unusual diagnosis.48

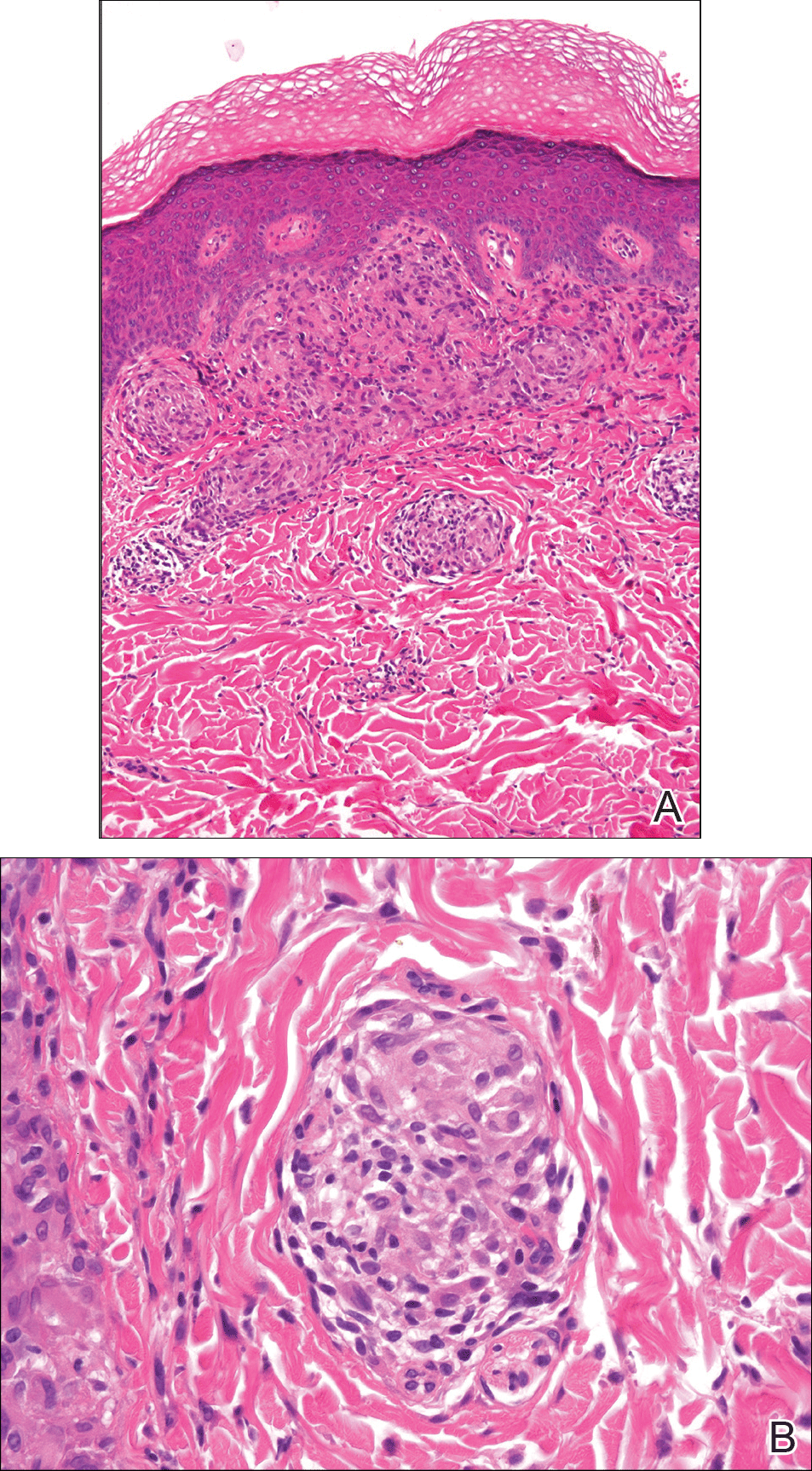

From a histopathologic perspective, MCD is characterized by discrete, noncaseating, sarcoidlike granulomas with abundant multinucleated giant cells (Langhans giant cells) in the superficial dermis (papillary), deep dermis (reticular), and adipose tissue (Figure).8,17 In the presence of concomitant intestinal disease, the granulomas of both the intestinal and dermal tissues should share the same microscopic characteristics.8 In addition, copious neutrophils and granulomas surrounding the microvasculature have been described,34 as well as general lymphocyte and plasma cell infiltrate.45 Some histologic samples have included collagen degeneration termed necrobiosis in the middle dermal layer as another variable finding in MCD.14,34

On microscopy, it has been reported that use of Verhoeff-van Gieson staining may be helpful to highlight the presence of neutrophil obstruction within the dermal vasculature, particularly the arterial lumen, as well as to aid in highlighting swelling of the endothelium with fragmentation of the internal elastic lamina.17 Although not part of the routine diagnosis, electron microscopy of MCD tissue samples have confirmed hypertrophy of the endothelial cells composing the capillaries with resulting extravasation of fibrin, red blood cells, lymphocytes, and epithelioid histiocytes.17 Observation of tissue under direct immunofluorescence has been less helpful, as it has shown only nonspecific fibrinogen deposition within the dermis and dermal vessels.17

In an article on treatment of MCD, Escher et al43 reinforced that the macroscopic findings of MCD are diverse, and the microscopic findings characteristic of MCD also can be mimicked by other etiologies such as sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, fungal infections, lymphogranuloma venereum, leishmaniasis, and connective tissue disorders.43 As such, the workup to rule out infectious, anatomic, and autoimmune etiologies should be diverse. Often, the workup for MCD will include special stains such as Ziehl-Neelsen stain to rule out Mycobacterium tuberculosis and acid-fast bacilli and Fite stain to consider atypical mycobacteria. Other tests such as tissue culture, chest radiograph, tuberculin skin test (Mantoux test), IFN-γ release assay, or polarized light microscopy may rule out infectious etiologies.9,49 Serologic testing might include VDRL test, Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and human immunodeficiency virus.5

Crohn disease is characterized histologically by sarcoidlike noncaseating granulomas, and as such, it is important to differentiate MCD from sarcoidosis prior to histologic analysis. Sarcoidosis also can be considered much less likely with a normal chest radiograph and in the absence of increased serum calcium and angiotensin-converting enzyme levels.7 The differentiation of sarcoidosis from MCD on the microscopic scale is subtle but is sometimes facilitated in the presence of an ulcerated epidermis or lymphocytic/eosinophilic infiltrate and edema within the dermis, all suggestive of MCD.14

Metastatic CD also should be differentiated from erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum, which are among the most common cutaneous findings associated with CD.14 Pyoderma gangrenosum can be distinguished histologically by identifying copious neutrophilic infiltrate with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia.50