Don’t Get Hung Up on Fishhooks: A Guide to Fishhook Removal

In the sport of fishing, barbed fishhooks often are used for their effectiveness in maintaining the fish on the hook once it is caught. However, if a fishhook is implanted in the skin of a fisherman or fisherwoman, a barb can pose problems in removing the fishhook without exacerbating internal injury, a common fear among outpatient physicians. We describe the case of a patient who presented to the dermatology clinic with a barbed fishhook injury and discuss several simple methods for barbed fishhook removal that can be easily utilized in the outpatient setting. Because failing to treat the patient may lead to further discomfort and increased risk for complications, practitioners should be familiar with the removal methods described here, as they are not time consuming and do not require complex equipment. Furthermore, these techniques may be useful for removal of other foreign bodies embedded in cutaneous tissue (eg, splinters).

Practice Points

- Barbed fishhooks should never be removed by pushing the hook in a retrograde manner along the path of insertion, as this method may result in extensive internal tissue destruction and increased complications.

- There are a number of safe and effective techniques for removing barbed fishhooks from cutaneous tissue that also may be applicable in removing other foreign bodies embedded in cutaneous tissue (eg, splinters).

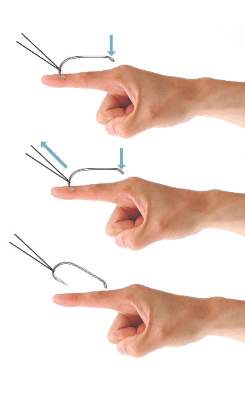

The string-pull method (Figure 4) has been credited to fishermen in South Australia and was first described by Cooke2 in 1961. This method is relatively painless, does not require anesthesia, and has a high success rate when properly administered. However, it does require rapid and confident motions (ie, without hesitation) by the practitioner and should not be performed on free-moving areas of the body (eg, earlobe).3 With this technique, a sturdy piece of suture (eg, 2/0 or 3/0 strength silk) is looped around the hook and is extended away from the practitioner at a 30° angle. The free end of the suture is then securely fastened around the index finger of the practitioner’s dominant hand. The index finger of the nondominant hand should apply a downward pressure to the hook shaft to disengage the barb from the tissue. Simultaneously and rather quickly and forcefully the practitioner must pull the dominant index finger with the string attached in a superior and lateral direction, as depicted by the long arrow in Figure 4. If successful, the barbed hook will pull out of the entrance site. The use of string in pulling the fishhook parallel to the site of injury is helpful for smaller fishhooks that may be difficult to grab with fingers alone. However, with larger fishhooks, the string may not be required so long as the practitioner is able to obtain a secure grasp on the fishhook shaft. The string-pull method becomes particularly useful when anesthesia is unavailable or when the barb of the hook is embedded too deeply for safe advancement through tissue to visualize and cut the barb.

Lastly, the needle cover technique (Figure 5) is another simple method that does not require the creation of a secondary wound. An 18-gauge needle is simply inserted parallel to the fishhook curvature into the site of entry. By using the needle to slide along the fishhook’s curve, the practitioner is able to follow its pathway while in the tissue. The tip of the 18-gauge needle is then used to cap or cover the barb, thus allowing the fishhook to be removed in a retrograde fashion from the wound. In an outpatient setting, this technique does not require the creation of additional tissue damage and practitioners who are inexperienced with fishhook removal may proceed through the motions more slowly and methodically than the string-pull method permits.

Wound care following fishhook removal should involve adequate flushing of the wound with normal saline along with the application of topical antibiotics and a simple dressing and adhesive bandage. Oral prophylactic antibiotics typically are not required for shallow cutaneous injuries unless the fishhook is dirty, the patient is immunocompromised, or the patient has a condition lending to poor wound healing (eg, diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease).3 When deciding on antibiotics, it is important to note that fishhook injuries while saltwater fishing are associated with Vibrio infection, while injuries sustained during freshwater fishing are associated with gram-negative bacteria (eg, Pseudomonas and Aeromonas species).3 Lastly, it is essential to find out the immunization status of the patient, and tetanus immune globulin should be provided if necessary.

|

| |

| Figure 4. The string-pull method for fishhook removal. | Figure 5. The needle cover technique for fishhook removal. |

Conclusion

Although guidelines for barbed fishhook removal are not available, outpatient physicians, including dermatologists, should not fear removal procedures. There are many safe and effective fishhook removal methods that are not time consuming and do not require complex equipment. Furthermore, familiarization with these same techniques may be useful for removal of other foreign bodies embedded in cutaneous tissue.