Idiopathic Follicular Mucinosis or Mycosis Fungoides? Classification and Diagnostic Challenges

In recent years, the distinction between idiopathic follicular mucinosis (FM) and lymphoma-associated follicular mucinosis (LAFM) has been made through assessment of T-cell receptor gene rearrangement, flow cytometry, and immunohistochemistry. These methods, among others, have mostly identified monoclonality as a defining characteristic of LAFM; however, this finding cannot be considered conclusive, as monoclonality also has been described in benign inflammatory dermatoses such as lichen planus and idiopathic FM. Pure histologic diagnosis also is unreliable in many cases, as the histologic patterns of idiopathic FM and LAFM overlap. In this article, we discuss the importance of close clinical follow-up in patients with patch-stage mycosis fungoides (MF) or FM who have had a nondiagnostic histopathologic evaluation. We also highlight the value of ancillary testing, including T-cell receptor gene rearrangement, flow cytometry, and immunohistochemistry, as a component in the diagnostic process rather than the sole diagnostic moiety. Diagnosis and classification of idiopathic FM and LAFM continue to pose challenges for dermatologists, oncologists, and pathologists, and no single diagnostic tool is sufficient in providing diagnostic certainty; rather, a collective evaluation of pathologic, molecular, and clinical criteria is required. Currently, classification of idiopathic FM and LAFM incorporates clinical information and histologic assessment, but little consideration is given to the implications of the diagnosis from the patient’s perspective. Revisiting histologic classification of these entities while incorporating the patient’s perspective may prove beneficial to dermatologists as well as patients.

Practice Points

- An isolated patch in the head or neck area is much more likely to be follicular mucinosis (FM) than mycosis fungoides (MF).

- Monoclonality does not reliably distinguish FM from MF.

- Younger patients are more likely to have FM with spontaneous remission, and older patients are more likely to develop MF.

- None of the clinicopathologic features of FM or MF are without overlap.

Mycosis fungoides is more common in males and its incidence increases with age; however, diagnosis should not be ruled out based on age or gender. Typical presentation of early-stage disease includes erythematous patches or plaques, often with light scaling.19 Lesions routinely are of long-standing duration (months to years), are located in areas that are infrequently exposed to sunlight, and often are 5 cm in diameter or larger with irregular borders.21 Associated poikiloderma is relatively specific to MF but rarely is seen in other CTCLs, connective-tissue diseases, and some genodermatoses. Poikiloderma commonly is identified in LPP, which shows the same telangiectasia, mottled pigmentation, and epidermal atrophy as MF-associated poikiloderma, leading some to believe that there is no separation between the 2 conditions. In all stages of MF, lesions frequently are numerous and occur on multiple sites. Plaques and tumors can show spontaneous ulceration. When lesions are folliculotropic, they can cause localized alopecia, follicular-based papules, and fungating pseudotumors in more advanced stages.1 The clinical presentation of FM substantially overlaps with folliculotropic MF, and although FM lesions often are solitary and are located on the face or scalp, they also can present as multiple lesions located elsewhere on the body. It also has been proposed that folliculotropic MF should not be separated from FM-associated MF (or LAFM).22

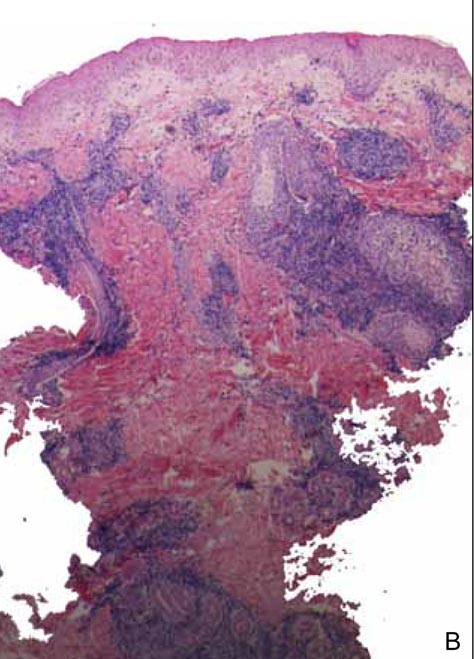

The characteristic histologic picture of LAFM in patch or plaque stage shows mucin deposition within hair follicles, similar to idiopathic FM. On histology, both conditions demonstrate dense lymphoid infiltrates around and within hair follicles as well as in the dermis (Figure). Most cases of LAFM show epidermotropism of lymphocytes between follicles, but this finding is not present in every case and often disappears when the disease advances to the tumor stage.1,19 Although Pautrier microabscesses (collections of lymphocytes within the superficial epidermis) are considered to be somewhat specific to MF, they are only present in a minority of cases.20 In a study by the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas,21 the only histopathologic criteria that showed any appreciable sensitivity or specificity in the diagnosis of MF were the presence of lymphoid cells with variable nuclear and cytoplasmic features and/or strikingly irregular nuclear contours with the presence of lymphocytes larger than those usually seen in inflammatory dermatoses. Despite these criteria, the study reported a high misclassification rate. A complicated scoring system for diagnosis of MF in patch- or early plaque-stage disease was proposed by the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas,21 which integrates clinical, histopathologic, molecular, and immunophenotypic criteria. However, these criteria have been continually debated in the literature and are only discussed in this article in relation to the association between MF and FM. Diagnosis of tumor-stage MF is not addressed in this article, as it is readily identified as lymphoma and is not easily confused with idiopathic FM.

|

Clinical assessment of a patient’s medical history to identify persistent and progressive disease is paramount to the diagnosis of MF. Although MF lesions tend to increase in size and number over time, this presentation is not without exception.21 In early patch-stage disease, eliminating some of the patient’s current medications may be sufficient in clearing cutaneous patches that cannot be conclusively identified as either MF or a benign inflammatory lymphoid infiltrate, which further emphasizes the importance of clinical assessment of the patient’s medical history in the diagnosis of MF. The shape of the lesions also is helpful in distinguishing between MF and other skin disorders, such as digitate dermatosis or LPP; unlike the latter, the waxing and waning nature of MF lesions often produces irregularly shaped patches with little coalescence. Again, there are some investigators who believe that these lesions represent varying presentations of MF.6

In a study by Cerroni et al,1 44 patients with FM were divided into 2 groups: (1) a cohort of 16 patients with no history or clinical evidence of MF or Sézary syndrome (ie, LAFM), and (2) a cohort of 28 patients with clinicopathologic evidence of CTCL. Patients in both groups were followed for a maximum of 20 years. Results indicated that that the presence of perifollicular or intrafollicular mucin, epidermotropism of lymphocytes, monoclonality, and epidemiologic characteristics (eg, age, sex, race) cannot reliably distinguish the 2 disease forms. Furthermore, it was suggested that these conditions are not mutually exclusive entities and are actually variants of CTCL. The observation that the 2 diseases share prognostic overlap adds further credence to the already puzzling conundrum. Nineteen of 28 patients with MF were alive and well at follow-up, and all patients in the idiopathic FM group were alive, with only 9 of 16 patients showing residual disease and none with CTCL.1