Massive liver metastasis from colon adenocarcinoma causing cardiac tamponade

Accepted for publication May 23, 2017

Correspondence aditya.halthore@gmail.com

Disclosures The authors report no disclosures/conflicts of interest.

Citation JCSO 2018;16(1):e37-e39

©2018 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0352

Related articles

Metastatic eccrine carcinoma with stomach and pericardial involvement

Oncology and the heart

Submit a paper here

Colorectal cancer is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in the United States.1 About 5% of Americans will be diagnosed with colorectal cancer in their lifetime, of which 20% will present with distant metastasis.2 The most common sites of metastasis are regional lymph nodes, liver, lung and peritoneum, and patients may present with signs or symptoms related to disease burden at any of these organs.

Case presentation and summary

A 55-year-old man had presented to an outside hospital in August of 2014 with 6 months of hematochezia and a 40-lb weight loss. He was found to be severely anemic on admission (hemoglobin, 4.9 g/dL [normal, 13-17 g/dL], hematocrit, 16% [normal, 35%-45%]). A computed-tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast revealed a mass of 6.9 x 4.7 x 6.3 cm in the rectosigmoid colon and a mass of 10.0 x 12.0 x 10.7 cm in the right hepatic lobe consistent with metastatic disease. The patient was taken to the operating room where the rectosigmoid mass was resected completely. The liver mass was deemed unresectable because of its large size, and surgically directed therapy could not be performed. Pathology was consistent with a T3N1 moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma 11 cm from the anal verge. Further molecular tumor studies revealed wild type KRAS and NRAS, as well as a BRAF mutation.

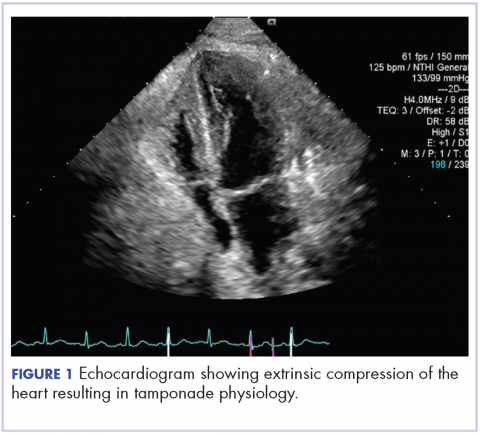

About 4 weeks after the surgery, the patient was seen at our institution for an initial consultation and was noted to have significant anasarca, including 4+ pitting lower extremity edema and scrotal edema. He complained of dyspnea on exertion, which he attributed to deconditioning. His resting heart rate was found to be 123 beats per minute (normal, 60-100 bpm). Jugular venous distention was present. The patient was sent for an urgent echocardiogram, which showed external compression of the right atrium and ventricle by his liver metastasis resulting in tamponade physiology without the presence of any pericardial effusion (Figure 1).

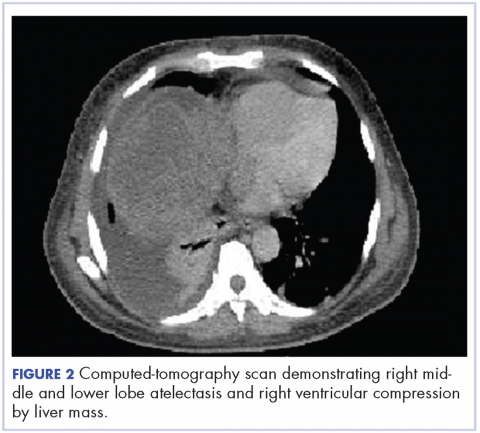

,A CT of the abdomen and pelvis at that time showed that the liver mass had increased to 17.6 x 12.1 x 16.1 cm, exerting pressure on the heart and causing atelectasis of the right middle and lower lung lobes (Figure 2).

Treatment plan

The patient was evaluated by surgical oncology for resection, but his cardiovascular status placed him at high risk for perioperative complications, so such surgery was not pursued. Radioembolization was considered but not pursued because the process needed to evaluate, plan, and treat was not considered sufficiently timely. We consulted with our radiation oncology colleagues about external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) for rapid palliation. They evaluated the patient and recommended the EBRT, and the patient signed consent for treatment. We performed a CT-based simulation and generated an external beam, linear-accelerator–based treatment plan. The plan consisted of three 15-megavoltage photon fields delivering 3,000 cGy in 10 fractions to the whole liver, with appropriate multileaf collimation blocking to minimize dose to adjacent heart, right lung, and bilateral kidneys (Figure 3).

Before initiation of the EBRT, the patient received systemic chemotherapy with a dose-adjusted FOLFOX regimen (5-FU bolus 200 mg/m2, leucovorin 200 mg/m2, oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2, with infusional 5-FU 2,400 mg/m2 over 46 hours). After completing 1 dose of modified FOLFOX, he completed 10 fractions of whole liver radiotherapy with the aforementioned plan. He tolerated the initial treatment well and his subjective symptoms improved. The patient then proceeded to further systemic therapy. After recent data demonstrated improved median progression-free survival and response rates with FOLFOXIRI plus bevacizumab (infusional 5-FU 3200 mg/m2, leucovorin 200 mg/m2, irinotecan 165 mg/m2, and oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2, bevacizumab 5 mg/kg) versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab,3 we decided to modify his systemic therapy to FOLFOXIRI with bevacizumab to induce a better response.