Given our chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and the advent of immune checkpoint inhibitors, oncology and cardiology may be more closely linked than ever before. This interview reviews the potential toxicities of today's radiation, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and the structural involvement that tumors may cause in and around the heart. Although the immune checkpoint inhibitors are not commonly associated with cardiac toxicity, their increasing use may tell us otherwise. This interview summarizes the close association between oncology and cardiology, which we should bear in mind as we treat our patients.

Correspondence David H Henry, MD; David.Henry@uphs.upenn.edu.

Disclosures The authors report no disclosures/conflicts of interest.

Citation JCSO 2017;15(3):e178-e182

©2017 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0348

Related articles

Sarcoidosis, complete heart block, and warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia

Congestive heart failure during induction with anthracycline-based therapy in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia

An unusual case of primary cardiac prosthetic valve-associated lymphoma

Submit a paper here

DR HENRY [DH] I am Dr David Henry with The Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology. I am speaking today with Dr Joe Carver at the University of Pennsylvania where he is chief of staff of the Abramson Cancer Center and holds the Bernard Fishman Clinical Professor of Medicine. The reason we’re talking today is that Dr Carver specializes in two areas that rarely overlap, cardiology and oncology. We thought we’d talk about how oncologists think about the heart. Patients may have comorbid illness of the heart and then we treat them, or our treatments may cause cardiac issues. So, let us begin with radiation therapy and cardiac toxicity. We have increasingly modern techniques. We hear our colleagues in radiation talk about intensity-modulated radiation therapy, Gamma Knife, CyberKnife, proton therapy, and what those might do to the heart. I’m thinking of the coronary arteries, mechanical function, and ejection fraction. So, Joe how would you describe that to a colleague who is worried about radiation and these more modern techniques? What do we need to watch for and how do we watch for it with regard to these functions?

DR CARVER [JC] It’s a great question. The answer about radiation and the heart really has to be divided into two different areas. If you’re talking to somebody who has had radiation in the past, especially in what we would call the premodern era, that population is at an increased risk for multiple different cardiac problems starting with myocardial dysfunction. In regard to the term premodern, depending on the facility, the transition to modern would have occurred sometime in the 1980s; prior to that shift, therapeutic radiation was delivered with little concern for cardiac exposure, and in many cases, the heart was blasted and nobody really monitored how much radiation the heart received. When due to radiation, myocardial dysfunction is more restrictive than congestive disease, valvular disease, coronary artery disease, and pericardial disease, as well as arrhythmias and conduction problems.

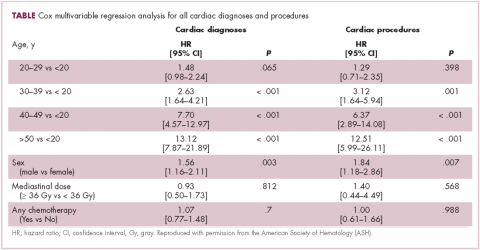

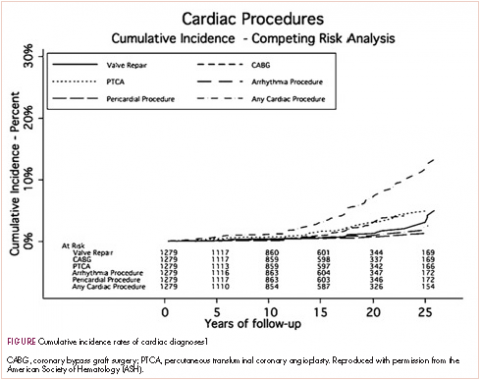

A typical example is a patient who had Hodgkin disease in his teens and received mediastinal mantle radiation. Fifteen to 25 years later, the patient has a pacemaker for heart block, coronary artery disease that requires a stent, and most recently has two valves replaced—so aortic and mitral valve replacement because of late radiation effects. This scenario is typical for the “old” days. The 20-year cumulative incidence of radiation-induced cardiac toxicity is 15%-20% (Table, Figure).1 Sitting with a patient about to begin chest radiation, the absolute risks are unknown but presumed to be less as treatment is delivered according to the modern techniques that you described in the question.