Good, bad, and ugly: Prior authorization and medicolegal risk

Dear Dr. Mossman,

Where I practice, most health care plans won’t pay for certain medications without giving prior authorization (PA). Completing PA forms and making telephone calls take up time that could be better spent treating patients. I’m tempted to set a new policy of not doing PAs. If I do, might I face legal trouble?

Submitted by “Dr. A”

If you provide clinical care, you’ve probably dealt with third-party payers who require prior authorization (PA) before they will pay for certain treatments. Dr. A is not alone in feeling exasperated about the time it takes to complete a PA.1 After spending several hours each month waiting on hold and wading through stacks of paperwork, you may feel like Dr. A and consider refusing to do any more PAs.

But is Dr. A’s proposed solution a good idea? To address this question and the frustration that lies behind it, we’ll take a cue from Italian film director Sergio Leone and discuss:

• how PAs affect psychiatric care: the good, the bad, and the ugly

• potential exposure to professional liability and ethics complaints that might result from refusing or failing to seek PA

• strategies to reduce the burden of PAs while providing efficient, effective care.

The good

Recent decades have witnessed huge increases in spending on prescription medication. Psychotropics are no exception; state Medicaid spending for anti-psychotic medication grew from <$1 billion in 1995 to >$5.5 billion in 2005.2

Requiring a PA for expensive drugs is one way that third-party payers try to rein in costs and hold down insurance premiums. Imposing financial constraints often is just one aim of a pharmacy benefit management (PBM) program. Insurers also justify PBMs by pointing out that feedback to practitioners whose prescribing falls well outside the norm—in the form of mailed warnings, physician second opinions, or pharmacist consultation—can improve patient safety and encourage appropriate treatment options for enrolled patients.3,4 Examples of such benefits include reducing overuse of prescription opioids5 and antipsychotics among children,3 misuse of buprenorphine,6 and adverse effects from potentially inappropriate prescriptions.7

The bad

The bad news for doctors: Cost savings for payers come at the expense of providers and their practices, in the form of time spent doing paperwork and talking on the phone to complete PAs or contest PA decisions.8 Addressing PA requests costs an estimated $83,000 per physician per year. The total administrative burden for all 835,000 physicians who practice in the United States therefore is 868,000,000 hours, or $69 billion annually.9

To make matters worse, PA requirements may increase the overall cost of care. After Georgia Medicaid instituted PA requirements for second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), average monthly per member drug costs fell $19.62, but average monthly outpatient treatment costs rose $31.59 per member.10 Pharmacy savings that result from requiring PAs for SGAs can be offset quickly by small increases in the hospitalization rate or emergency department visits.9,11

The ugly

Many physicians believe that the PA process undermines patient care by decreasing time devoted to direct patient contact, incentivizing suboptimal treatment, and limiting medication access.1,12,13 But do any data support this belief? Do PAs impede treatment for vulnerable persons with severe mental illnesses?

The answer, some studies suggest, is “Yes.” A Maine Medicaid PA policy slowed initiation of treatment for bipolar disorder by reducing the rate of starting non-preferred medications, although the same policy had no impact on patients already receiving treatment.14 Another study examined the effect of PA processes for inpatient psychiatry treatment and found that patients were less likely to be admitted on weekends, probably because PA review was not available on those days.15 A third study showed that PA requirements and resulting impediments to getting refills were correlated with medication discontinuation by patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, which can increase the risk of decompensation, work-related problems, and hospitalization.16

Problems with PAs

Whether they are helpful or counterproductive, PAs are a practice reality. Dr. A’s proposed solution sounds appealing, but it might create ethical and legal problems.

Among the fundamental elements of ethical medical practice is physicians’ obligation to give patients “guidance … as to the optimal course of action” and to “advocate for patients in dealing with third parties when appropriate.”17 It’s fine for psychiatrists to consider prescribing treatments that patients’ health care coverage favors, but we also have to help patients weigh and evaluate costs, particularly when patients’ circumstances and medical interests militate strongly for options that third-party payers balk at paying for. Patients’ interests—not what’s expedient—are always physicians’ foremost concern.18

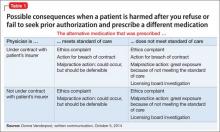

Beyond purely ethical considerations, you might face legal consequences if you refuse or fail to seek PAs for what you think is the proper medication. As Table 1 shows, one key factor is whether you are under contract with the patient’s insurance carrier; if you are, failure to seek a PA when appropriate may constitute a breach of the contract (Donna Vanderpool, written communication, October 5, 2014).

If the prescribed medication does not meet the standard of care and your patient suffers some harm, a licensing board complaint and investigation are possible. You also face exposure to a medical malpractice action. Although we do not know of any instances in which such an action has succeeded, 2 recent court decisions suggest that harm to a patient stemmed from failing to seek PA for a medication could constitute grounds for a lawsuit.19,20 Efforts to contain medical costs have been around for decades, and courts have held that physicians, third-party payers, and utilization review intermediaries are bound by “the standard of reasonable community practice”21 and should not let cost limitations “corrupt medical judgment.”22 Physicians who do not appeal limitations at odds with their medical judgment might bear responsibility for any injuries that occur.18,22

Managing PA requests

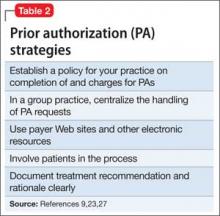

Given the inevitability of encountering PA requests and your ethical and professional obligations to help patients, what can you do (Table 29,23,27)?