Antipsychotics for obsessive-compulsive disorder: Weighing risks vs benefits

Mr. E, age 37, has a 20-year history of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), with comorbid generalized anxiety disorder and hypertension. His medication regimen consists of

Box

Antipsychotics for OCD: What the guidelines recommend

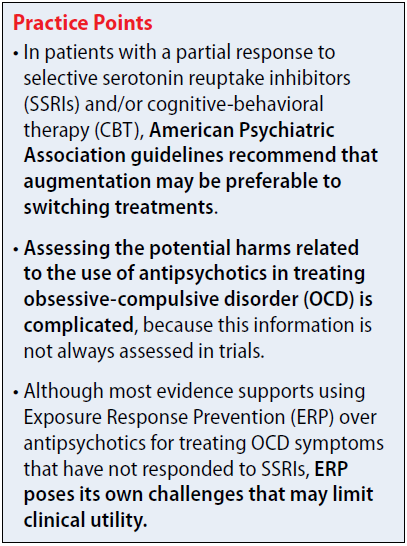

The 2013 American Psychiatric Association (APA) obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) treatment guidelines include recommendations regarding the use of antipsychotics in patients who do not respond to first-line treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and/or cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). The APA recommends evaluating contributing factors, including comorbidities, family support, and ability to tolerate psychotherapy or maximum recommended drug doses, before augmenting or switching therapies.1

In patients with a partial response to SSRIs and/or CBT, the APA suggests that augmentation may be preferable to switching treatments. Augmentation strategies for SSRIs include antipsychotics or CBT with Exposure Response Prevention (ERP); augmentation strategies for CBT include SSRIs. Combining SSRIs and CBT may decrease the chance of relapse when medication is discontinued. If the patient has a partial response to ERP, intensification of therapy also can be considered based on patient-specific factors. In non-responders, switching therapies may be necessary. Alternative treatments including a different SSRI; an antidepressant from a difference class, such as clomipramine or mirtazapine; an antipsychotic; or CBT.

The 2006 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines for OCD recommend additional high-intensity CBT, adding an antipsychotic to an SSRI or clomipramine, or combining clomipramine with citalopram in non-responders. There is no guidance regarding the order in which these treatments should be trialed. Antipsychotics are recommended as an entire class, and there are no recommendations regarding dosing or long-term risks. These guidelines are based on limited evidence, including only 1 trial of quetiapine and 1 trial of olanzapine.2,3

Efficacy

The 2013 National Institute for Health Care and Excellence Evidence Update included a 2010 Cochrane Review of 11 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of antipsychotics as adjunctive treatment to SSRIs.5 All trials were <6 months, and most were limited regarding quality aspects. Two trials found no statistically significant difference with olanzapine in efficacy measures (Y-BOCS mean difference [MD] −2.96; 95% confidence interval [CI] −7.41 to 1.22; effect size d = −2.96 [−7.14, 1.22]). Among patients with no clinically significant change (defined as ≤35% reduction in Y-BOCS), there was no significant difference between groups (n = 44, 1 RCT, odds ratio [OR] 0.76; 95% CI 0.17 to 3.29; effect size d = 0.76 [0.17, 3.29]). Studies found increased weight gain with olanzapine compared with antidepressant monotherapy.

Statistically significant differences were demonstrated with the addition of quetiapine to antidepressant monotherapy as shown in Y-BOCS score at endpoint (Y-BOCS MD −2.28; 95% CI −4.05 to −0.52; effect size d −2.28 [−4.05, −0.52]). Quetiapine also demonstrated benefit for depressive and anxiety symptoms. Among patients with no clinically significant change (defined as ≤35% reduction in Y-BOCS), there was a significant difference between groups (n = 80, 2 RCTs, OR 0.27; 95% CI 0.09 to 0.87; effect size d = 0.27 [0.09, 0.87]).

Adjunctive treatment with risperidone was superior to antidepressant monotherapy for participants without a significant response in OCD symptom severity of at least 25% with validated measures (OR 0.17; 95% CI 0.04 to 0.66; effect size d = 0.17 [0.04, 0.66]), and in depressive and anxiety symptoms. Mean reduction in Y-BOCS scores was not statistically significant with risperidone (MD −3.35; 95% CI −8.25 to 1.55; effect size d = −3.35 [−8.25, 1.55]).5