Antisynthetase syndrome: Not just an inflammatory myopathy

ABSTRACTIn recent years, antisynthetase syndrome has been recognized as an important cause of autoimmune inflammatory myopathy in a subset of patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis. It is associated with serum antibodies to aminoacyl-transfer RNA synthetases and is characterized by a constellation of manifestations, including fever, myositis, interstitial lung disease, “mechanic’s hands,” Raynaud phenomenon, and polyarthritis. Physicians should be familiar with its variety of clinical presentations and should include it in the differential diagnosis in patients presenting with unexplained interstitial lung disease.

KEY POINTS

- Antisynthetase syndrome can present with a wide variety of clinical manifestations, including myositis and interstitial lung disease.

- The type and severity of interstitial lung disease usually determine the long-term outcome.

- In the appropriate clinical setting, the diagnosis is usually confirmed by the detection of antibodies to various aminoacyl-transfer RNA synthetases, anti-Jo-1 antibody being the most common.

- Although glucocorticoids are considered the mainstay of treatment, additional immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine or methotrexate are often required as steroid-sparing agents and also to achieve disease control.

- In the case of severe pulmonary involvement, cyclophosphamide is recommended.

Mechanic’s hands

In about 30% of patients, the skin of the tips and margins of the fingers becomes thickened, hyperkeratotic, and fissured, the appearance of which is classically described as mechanic’s hands. It is a common manifestation of antisynthetase syndrome and is particularly prominent on the radial side of the index fingers (Figure 1). Biopsy of affected skin shows an interface psoriasiform dermatitis.19 In addition, some dermatomyositis patients with Gottron papules and a heliotrope rash have antisynthetase antibodies.

Raynaud phenomenon

Raynaud phenomenon develops in about 40% of patients. Some have nailfold capillary abnormalities.20 However, persistent or severe digital ischemia leading to digital ulceration or infarction is uncommon.21

Inflammatory arthritis

Arthralgias and arthritis are common (50%), the most common form being a symmetric polyarthritis of the small joints of the hands and feet. It is typically nonerosive but can sometimes be erosive and destructive.20

Because inflammatory arthritis mimics rheumatoid arthritis, antisynthetase syndrome should be considered in rheumatoid factor-negative patients presenting with polyarthritis.

ASSOCIATION WITH MALIGNANCY

Traditional teaching has been that antisynthetase antibody is protective against an underlying malignancy.22,23 However, several recently published case studies have reported various malignancies occurring within 6 to 12 months of the diagnosis of antisynthetase syndrome.7,24 The debate as to whether these are chance associations or causal (a paraneoplastic phenomenon) has not been resolved at this time.24

It is now recommended that patients with antisynthetase syndrome be screened for malignancies as appropriate for the patient’s age and sex. Screening should include a careful history and physical examination, complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, chest radiography, mammography, and a gynecologic examination for women.25 If abnormalities are found, a more thorough evaluation for cancer is appropriate.

DIAGNOSIS

Muscle enzyme levels are often elevated

Muscle enzymes (creatine kinase and aldolase) are often elevated. Serum creatine kinase levels can range between 5 to 50 times the upper limit of normal. In an established case, creatine kinase levels along with careful manual muscle strength testing may help evaluate myositis activity. However, in chronic and advanced disease, creatine kinase may be within the normal range despite active myositis, partly because of extensive loss of muscle mass. In myositis, it may be prudent to check both creatine kinase and aldolase; sometimes only serum aldolase level rises, when immune-mediated injury predominantly affects the early regenerative myocytes.26

Judicious use of autoantibody testing

The characteristic clinical presentation is the initial clue to the diagnosis of antisynthetase syndrome, which is then supported by serologic testing.

Injudicious testing for a long list of antibodies should be avoided, as the cost is considerable and it does not influence further management. However, ordering an anti-Jo-1 antibody test in the correct clinical setting is appropriate, as it has high specificity,27,28 and thus can help establish or refute the clinical suspicion of antisynthetase syndrome.

Screening pulmonary function testing and thoracic high-resolution computed tomography for all patients with polymyositis or dermatomyositis is not considered “standard of care” and will likely not be reimbursed by third-party payers. However, in a patient with symptoms and signs of myositis, the presence of an antisynthetase antibody should prompt screening for occult interstitial lung disease, even in the absence of symptoms. As lung disease ultimately determines the prognosis in antisynthetase syndrome, early diagnosis and management is the key. Therefore, these tests would likely be approved to establish the diagnosis of interstitial lung disease and evaluate its severity.

If a myositis patient is also found to have interstitial lung disease or develops mechanic’s hands, the likely diagnosis is antisynthetase syndrome, which can be confirmed by serologic testing for antisynthetase antibodies. Interstitial lung disease in antisynthetase syndrome is often from “nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis”; therefore, medications tested and proven effective for this condition should be approved and reimbursed by payers.29–32

The coexistence of myositis and interstitial lung disease increases the sensitivity of anti-Jo-1 antibody.11 Thus, the clinician can have more confidence in early recognition and initiation of aggressive but targeted disease-modifying therapy.

Various methods can be used for detecting antisynthetase antibodies, with comparable results.28 Anti-Jo-1 antibody testing costs about $140. If that test is negative and antisynthetase syndrome is still suspected, then testing for the non-Jo-1 antisynthetase antibodies may be justified (Table 1). Though the cost of this panel of autoantibodies is about $300, it helps to confirm the diagnosis, and it influences the choice of second-line immunosuppressive agents such as tacrolimus29 and rituximab32 in patients resistant to conventional immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine and methotrexate.

Often, anti-Ro52 SS-A antibodies are present concurrently in patients with anti-Jo-1 syndrome.33 In observational studies in patients with anti-Jo-1 antibody-associated interstitial lung disease, coexistence of anti-Ro52 SS-A antibody tended to predict a worse pulmonary outcome than in those with anti-Jo-1 antibody alone.34,35

Electromyography

Electromyography not only helps differentiate between myopathic and neuropathic weakness, but it may also support the diagnosis of “inflammatory” myopathy as suggested by prominent muscle membrane irritability (fibrillations, positive sharp waves) and abnormal motor unit action potentials (spontaneous activity showing small, short, polyphasic potentials and early recruitment). However, the findings can be nonspecific, and may even be normal in 10% to 15% of patients.36 Electromyographic abnormalities are most consistently observed in weak proximal muscles, and electromyography is also helpful in selecting a muscle for biopsy. Although no single electromyographic pattern is considered diagnostic for inflammatory myopathy, abnormalities are present in around 90% of patients (Table 2).3

Magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging may show increased signal intensity in the affected muscles and surrounding tissues (Figure 3).37 Because it lacks sensitivity and specificity, magnetic resonance imaging is not helpful in diagnosing the disease. However, in the correct clinical setting, it may be used to guide muscle biopsy, and it can help in monitoring the disease progress.38

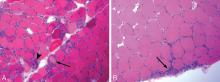

Muscle histopathology

Muscle biopsy, though often helpful, is not always diagnostic, and antisynthetase syndrome should still be suspected in the right clinical context, even in the absence of characteristic pathologic changes.

Biopsy of sites recently studied by electromyography should be avoided, and if the patient has undergone electromyography recently, the contralateral side should be selected for biopsy.

Reports of histopathologic findings in muscle biopsies in patients with antisynthetase syndrome document inflammatory myopathic features (Figure 4). In a series of patients with anti-Jo-1 syndrome, inflammation was noted in all cases, predominantly perimysial in location, with occasional endomysial and perivascular inflammation.39 Many of the inflammatory cells seen were macrophages and lymphocytes, in contrast to the predominantly lymphocytic infiltrates described in classic polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Perifascicular atrophy, similar to what is seen in dermatomyositis, was encountered; however, vascular changes, typical of dermatomyositis, were absent. Occasional degenerating and regenerating muscle fibers were also observed in most cases. Additionally, a characteristic perimysial connective tissue fragmentation was described, a feature less often seen in classic polymyositis and dermatomyositis.39