Assessing benefits and risks of hormone therapy in 2008: New evidence, especially with regard to the heart

ABSTRACT

Observational studies, including the observational component of the Women's Health Initiative, consistently found that women who chose to use menopausal hormone therapy (HT) had a reduction in mortality and cardiovascular disease incidence relative to women who did not use HT. Randomized controlled trials have taught us that initiation of HT in older women (> 60 years old) remote from menopause (> 10 years since menopause) potentially has more risk than benefit. Additionally, randomized controlled trials have confirmed observational studies indicating the safety and benefit of HT in young (< 60 years old) recently menopausal women (< 10 years since menopause). In other words, we have come full circle in our understanding of HT, with a caveat concerning initiation in older women. Importantly, the magnitude and types of risk associated with HT are similar to those of other commonly used therapies. These data have led to recommendations that the benefits of HT exceed the risks when initiated in menopausal women younger than 60 years.

HORMONE THERAPY IN CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE

Comparative effects of lipid-lowering therapy and HT

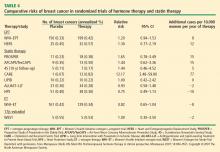

Examination of the evidence regarding lipid-lowering therapy for prevention of CHD, as well as its effects on breast cancer risk and coronary artery calcium scores in women, can add some much-needed perspective and context to the HT data reviewed above.

CHD prevention. Walsh and Pignone examined six randomized controlled trials (N = 11,435) of primary prevention with lipid-lowering medication in women and found no significant effect on CHD events, nonfatal myocardial infarction, CHD mortality, or total mortality.34 In eight randomized controlled trials of secondary prevention (N = 8,272), lipid-lowering therapy in women resulted in significant reductions in CHD end points but had no effect on total mortality.34

Atherosclerosis progression. In three randomized controlled trials, 1 to 4 years of statin therapy had no effect on the progression of coronary artery calcium compared with placebo.41–43 Among 1,064 women 50 to 59 years old who participated in a WHI substudy called the WHI Coronary Artery Calcium Study (WHI-CACS), those who were randomized to ET had significantly less coronary artery calcium at year 7 compared with those assigned to placebo.44 The mean Agatston coronary artery calcium scores were 83.1 with ET versus 123.1 with placebo (P = .02).

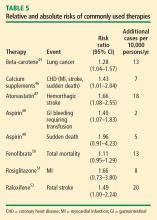

Comparing risk of HT with risk of other therapies

Other comparisons yield similar conclusions.35 For instance, a comparison of the ET arm of the WHI randomized trial with raloxifene in the Raloxifene Use for the Heart (RUTH) trial52 reveals similar effects on CHD, stroke, VTE, pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, and breast cancer, with the only large difference being a greater reduction in bone fracture risk with ET compared with raloxifene.35 Finally, in putting the risk of VTE with HT into perspective, consider that the risk of thromboembolic events with selective estrogen receptor modulators52 and with the fibric acid derivative fenofibrate in diabetics50 is of similar magnitude as the risk with HT.

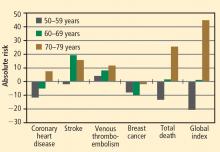

Risk must be viewed in light of age at HT initiation

CONCLUSIONS FROM RANDOMIZED TRIALS

HT’s effects on CHD and mortality: Timing is everything

Cumulative data from randomized trials indicate that in the overall population of women studied, HT, aspirin, and lipid-lowering therapy each have a null effect on the incidence of CHD and mortality. However, within this overall null effect, early initiation of HT (in terms of time from menopause [< 10 years] and age at initiation [< 60 years]) is associated with reductions in total mortality and CHD incidence. Additionally, a duration of HT use beyond 5 years is associated with a reduction in the incidence of CHD.9,10,20,28,29 These effects of the timing and duration of therapy are unique to HT. Unopposed ET may have an advantageous profile relative to EPT for reducing the incidence of CHD and mortality in postmenopausal women.

Gaining perspective on risks

The risks of stroke and VTE associated with HT are low for women overall and lower still for women who are within 10 years of menopause or younger than age 60 when they start HT. With respect to stroke, fewer cases of stroke developed in users of ET compared with placebo in women who started HT before age 60. The risks of EPT are comparable to those of other medications commonly used in this population of women. More broadly, the magnitude and types of risk associated with HT are similar to those associated with other commonly used therapies.

In addition, the underappreciated benefits of HT, such as potential prevention of diabetes mellitus (15 fewer cases of incident diabetes per 10,000 women per year with EPT and 14 fewer cases with ET), need to be recognized and discussed with our patients. These data are consistent in both observational studies and randomized trials.

The bottom line

As data from randomized trials of HT accumulate, the results are clearly similar to those from the more than 20 observational studies indicating that young, symptomatic postmenopausal women who use HT for long periods have lower rates of CHD and total mortality compared with postmenopausal women who do not use HT. Consistent with these data, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists issued a position statement in 2008 concluding that for symptomatic menopausal women under the age of 60, the benefits of HT exceed the risks.53

Nevertheless, the bottom line remains that the estrogen-cardioprotective hypothesis has yet to be studied, since randomized trials have not been conducted in the same population of women from which the hypothesis was generated. This hypothesis will be directly evaluated, however, in the ongoing Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol (ELITE). This randomized trial, funded by the National Institute on Aging, is designed to determine the effects of 17β-estradiol on the progression of atherosclerosis, cognition, and other postmenopausal health issues in recently menopausal (< 6 years) and remotely menopausal (≥ 10 years) women with no history of cardiovascular disease or diabetes. Until data from trials like ELITE emerge, guidelines such as those from the North American Menopause Society54 (reviewed in the next article in this supplement) are reasonable for clinical practice.