Assessing benefits and risks of hormone therapy in 2008: New evidence, especially with regard to the heart

ABSTRACT

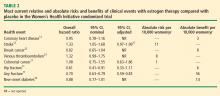

Observational studies, including the observational component of the Women's Health Initiative, consistently found that women who chose to use menopausal hormone therapy (HT) had a reduction in mortality and cardiovascular disease incidence relative to women who did not use HT. Randomized controlled trials have taught us that initiation of HT in older women (> 60 years old) remote from menopause (> 10 years since menopause) potentially has more risk than benefit. Additionally, randomized controlled trials have confirmed observational studies indicating the safety and benefit of HT in young (< 60 years old) recently menopausal women (< 10 years since menopause). In other words, we have come full circle in our understanding of HT, with a caveat concerning initiation in older women. Importantly, the magnitude and types of risk associated with HT are similar to those of other commonly used therapies. These data have led to recommendations that the benefits of HT exceed the risks when initiated in menopausal women younger than 60 years.

WHI: ET vs placebo

CHD. Importantly, no significant difference was found between the ET and placebo arms with respect to CHD events in the overall cohort of women, whose average age was 64 years.12

Stroke. The risk of stroke was greater with ET than with placebo in the nominal analysis, but importantly, the difference in event rates (11 per 10,000 women per year of therapy) failed to reach significance in the adjusted analysis.11,12

Breast cancer. A strong but nonsignificant trend toward a reduction in breast cancer risk was apparent in the ET arm (8 fewer breast cancer cases per 10,000 women per year of therapy). Among women who actually were adherent to their study regimen (ie, consuming ≥ 80% of their study medication), there was a statistically significant 33% reduction in breast cancer risk with ET relative to placebo.22 Importantly, the reduction in breast cancer risk relative to placebo was found across all the age ranges studied.11

VTE. The excess risk of VTE with ET versus placebo (32%) was less than the excess risk of VTE associated with EPT (Table 1). Importantly, the risk of VTE associated with ET was not statistically significant.11,23

Fracture. The risk of any fracture (hip or vertebral) was reduced significantly in the ET arm compared with the placebo arm.11

Diabetes. In a nominal analysis, there was a trend toward a reduction in the risk of new-onset diabetes in women randomized to ET relative to placebo, which nearly achieved statistical significance.24

WHAT EXPLAINS THE DISCORDANCE BETWEEN OBSERVATIONAL AND RANDOMIZED TRIALS OF HT?

How can the perceived discordance between the results from observational studies and those from randomized controlled trials be explained? There are currently three hypotheses:

- The populations differ in the two types of study designs (observational studies and randomized controlled trials)

- The duration of HT use differs

- The timing of HT initiation differs in relation to age, time since menopause, and stage of atherosclerosis.

Population characteristics

One obvious difference between randomized trials and observational studies of HT is the presence of menopausal symptoms. To maintain blinding, women with hot flashes were predominantly excluded from randomized trials of HT, whereas the presence of hot flashes is the predominant menopausal symptom of women included in observational studies and the main reason women seek HT from their providers.

Other consistent and possibly explanatory differences between clinical trials and observational studies of HT are patient age at enrollment, years since menopause, and body mass index (BMI). Comparing randomized controlled trials with observational studies, age at enrollment was much higher in the clinical trials (mean age ≥ 63 years) than in the observational studies (range of 30 to 55 years). Similarly, women enrolled in randomized trials were more than 10 years beyond menopause, whereas those in observational studies were less than 5 years beyond menopause. In fact, more than 80% of HT users in observational studies initiated HT within 1 or 2 years of menopause.

Additionally, women in randomized trials of HT tend to have higher BMIs than their counterparts in observational studies. For example, mean BMI was considerably higher in the WHI randomized trials (28.5 kg/m2 and 30.1 kg/m2)1,11 than in the observational Nurses’ Health Study (25.8 kg/m2),25 and a full third (34%) of women in the WHI randomized trials were severely obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2).

This point about BMI is noteworthy in light of findings on the effect of BMI on breast cancer risk from an analysis of the WHI observational study among 85,917 women aged 50 to 79 years old at enrollment.26 This analysis found that BMI was unrelated to breast cancer risk among women who had used HT; however, among nonusers of HT, a baseline BMI greater than 31.1 kg/m2 was associated with a 2.52 relative risk of breast cancer compared with a baseline BMI less than 22.6 kg/m2. The risk of breast cancer with increasing BMI was most pronounced in younger postmenopausal women. One interpretation is that high endogenous estrogen levels in postmenopausal women with an elevated BMI serve to increase breast cancer risk to a level beyond which HT adds no further risk. Alternatively, conjugated equine estrogens may act through a selective estrogen receptor modulator mechanism to block any potential adverse breast tissue effects of elevated endogenous estrone and estradiol levels.