Sleep apnea and the heart

Release date: September 1, 2019

Expiration date: August 31, 2022

Estimated time of completion: 0.75 hour

Click here to start this CME activity.

ABSTRACT

The normal sleep-wake cycle is characterized by diurnal variations in blood pressure, heart rate, and cardiac events. Sleep apnea disrupts the normal sleep-heart interaction, and the pathophysiology varies for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and central sleep apnea (CSA). Associations exist between sleep-disordered breathing (which encompasses both OSA and CSA) and heart failure, atrial fibrillation, stroke, coronary artery disease, and cardiovascular mortality. Treatment options include positive airway pressure as well as adaptive servo-ventilation and phrenic nerve stimulation for CSA. Treatment improves blood pressure, quality of life, and sleepiness, the last particularly in those at risk for cardiovascular disease. Results from clinical trials are not definitive in terms of hard cardiovascular outcomes.

KEY POINTS

- Diurnal variations in blood pressure, heart rate, and cardiac events occur during normal sleep.

- While normal sleep may be cardioprotective, sleep apnea disrupts the normal sleep-heart interaction.

- Untreated severe sleep apnea increases the risk for cardiovascular events.

- Treatment with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) may reduce the risk of cardiac events based on some data, though randomized studies suggest no improvement in cardiovascular mortality.

- Poor patient adherence to CPAP makes it difficult to evaluate the efficacy of CPAP treatment in clinical trials.

SLEEP APNEA AND HEART FAILURE

Both OSA and CSA are prevalent in patients with heart failure and may be associated with the progression of heart failure. CSA often occurs in patients with heart failure. The pathophysiology is multifactorial, including pulmonary congestion that results in stretch of the J receptors in the alveoli, prolonged circulation time, and increased chemosensitivity.

Complex pathways in the neuroaxis or somnogenic biomarkers of inflammation or both may be implicated in the paradoxical lack of subjective sleepiness in the presence of increased objective measures of sleepiness in systolic heart failure. One study found a relationship with one biomarker of inflammation and oxidative stress as it relates to objective symptoms of sleepiness but not subjective symptoms of sleepiness.28

Another contributing factor in the relationship between OSA and CSA in heart failure has also been described related to rostral shifts in fluid to the neck and to the pulmonary receptors in the alveoli of the lungs.29 These rostral shifts in fluids may contribute to sleep apnea with parapharyngeal edema leading to OSA and pulmonary congestion leading to CSA.

,Sleep apnea is associated with increased post-discharge mortality and hospitalization readmissions in the setting of acute heart failure.30 Mortality analysis of 1,096 patients admitted for decompensated heart failure found CSA and OSA were independently associated with mortality in patients compared with patients with no or minimal sleep-disordered breathing.30

CSA has also been shown to be a predictor of readmission in patients admitted for heart failure exacerbations.31 Targeting underlying CSA may reduce readmissions in those admitted with acute decompensated heart failure. While men were identified to be at increased risk of death relative to sleep-disordered breathing based on the initial results of the Sleep Heart Health Study, a subsequent epidemiologic substudy reflective of an older age group showed that OSA was more strongly associated with left ventricular mass index, risk of heart failure, or death in women compared with men.32

Treatment

Standard therapy for treatment of OSA is CPAP. Adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV) and transvenous phrenic nerve stimulation are also available as treatment options in certain cases of CSA.

One of the first randomized controlled trials designed to assess the impact of CSA treatment on survival in patients with heart failure initially favored the control group then later the CPAP group and was terminated early based on stopping rules.33,34 While adherence to therapy was suboptimal at an average of 3.6 hours, post hoc analysis showed that patients with CSA using CPAP with effective suppression of CSA had improved survival compared with patients who did not have effective suppression using CPAP.34

ASV is mainly used for treatment of CSA. In ASV, positive airway pressure for ventilation support is provided and adjusts as apneic episodes are detected during sleep. The support provided adapts to the physiology of the patient and can deliver breaths and utilize anticyclic modes of ventilation to address crescendo-decrescendo breathing patterns observed in Hunter-Cheyne-Stokes respiration.

In the Treatment of Sleep-Disordered Breathing With Predominant Central Sleep Apnea by Adaptive Servo Ventilation in Patients With Heart Failure (SERVE-HF) trial, 1,300 patients with systolic heart failure and predominantly CSA were randomized to receive ASV vs solely standard medical management.35 The primary composite end point included all-cause mortality or unplanned admission or hospitalization for heart failure. No difference was found in the primary end point between the ASV and the control group; however, there was an unanticipated negative impact of ASV on cardiovascular outcomes in some secondary end points. Based on the secondary outcome of cardiovascular-specific mortality, clinicians were advised that ASV was contraindicated for the treatment of CSA in patients with symptomatic heart failure with a left ventricular ejection fraction less than 45%. The interpretation of this study was complicated by several methodologic limitations.36

The Cardiovascular Improvements With Minute Ventilation-Targeted Adaptive Servo-Ventilation Therapy in Heart Failure (CAT-HF) randomized controlled trial also evaluated ASV compared with standard medical management in 126 patients with heart failure.37 This trial was terminated early because of the results of the SERVE-HF trial. Compliance with therapy was suboptimal at an average of 2.7 hours per day. The composite end point did not differ between the 2 groups; however, this was likely because the study was underpowered and was terminated early. Subgroup analysis revealed that patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction may benefit from ASV; however, additional studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Therefore, although ASV is not indicated when there is predominantly CSA in patients with systolic heart failure, preliminary results support potential benefit in patients with OSA and preserved ejection fraction.

Another novel treatment for CSA is transvenous phrenic nerve stimulation. A device is implanted that stimulates the phrenic nerve to initiate breaths. The initial study of transvenous phrenic nerve stimulation reported a significant reduction in the number of episodes of central apnea per hour of sleep.38,39 The apnea–hypopnea index improved overall and some types of obstructive apneic events were reduced with transvenous phrenic nerve stimulation.

A multicenter randomized control trial of transvenous phrenic nerve stimulation found improvement in several sleep apnea indices, including central apnea, hypoxia, reduced arousals from sleep, and patient reported well-being.40 Transvenous phrenic nerve stimulation holds promise as a novel therapy for central predominant sleep apnea not only in terms of improving the degree of central apnea and sleep-disordered breathing, but also in improving functional outcomes. Longitudinal and intereventional trial data are needed to clarify the impact of transvenous phrenic nerve stimulation on long-term cardiac outcomes.

SLEEP APNEA AND ATRIAL FIBRILLATION AND STROKE

Atrial fibrillation

AF is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia. The number of Americans with AF is projected to increase from 2.3 million to more than 10 million by the year 2050.41 The increasing incidence and prevalence of AF is not fully explained by the aging population and established risk factors.42 Unrecognized sleep apnea, estimated to exist in 85% or more of the population, may partially account for the increasing incidence of AF.43

There are 3 types of AF, which are thought to follow a continuum: paroxysmal AF is characterized by episodes that occur intermittently; persistent AF is characterized by episodes that last longer than 7 days; chronic or permanent AF is typically characterized by AF that is ongoing over many years.44 As with sleep apnea, AF is often asymptomatic and is likely underdiagnosed.

Sleep apnea and AF share several risk factors. Obesity is a risk factor for both OSA and AF; however, a meta-analysis supported a stronger association of OSA and AF vs obesity and AF.45 Increasing age is a risk factor for both OSA and AF.46,47 Although white populations are at higher risk for AF, OSA is associated with a 58% increased risk of AF in African Americans.48 Nocturnal hypoxia has been associated with increased risk of AF in Asians.49

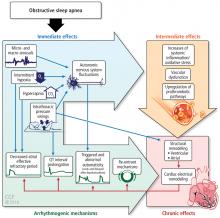

Experimental data continue to accrue providing biologic plausibility of the relationship between sleep apnea and AF. OSA contributes to structural and electrical remodeling of the heart with evidence supporting increased fibrosis and electrical remodeling in patients with OSA compared with a control group.51 Markers of structural remodeling, such as atrial size, electrical silence, and atrial voltage conduction velocity, are altered in OSA.50

Data from the Sleep Heart Health Study show very strong associations between atrial and ventricular cardiac arrhythmias and sleep apnea with two- to fivefold higher odds of arrhythmias in patients with severe OSA compared with controls even after accounting for confounding factors such as obesity.52

A multicenter, epidemiological study of older men showed that increasing severity of sleep apnea corresponds with an increased prevalence of AF and ventricular ectopy.53 This graded dose-response relationship suggests a causal relationship between sleep apnea and AF and ventricular ectopy. There also appears to be an immediate influence of apneic events and hypopneic events as it relates to arrhythmia. A case-crossover study showed an associated 18-fold increased risk of nocturnal arrhythmia within 90 seconds of an apneic or hypopneic event.54 This association was found with paroxysms of AF and with episodes of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia.

Data from a clinic-based cohort study show an association between AF and OSA.55 Specifically, increased severity of sleep apnea was associated with an increased prevalence of AF. Increasing degree of hypoxia or oxygen-lowering was also associated with increased incidence of AF or newly identified AF identified over time.

Longitudinal examination of 2 epidemiologic studies, the Sleep Heart Health Study and Outcomes of Sleep Disorders Study in Older Men, found CSA to be predictive of AF with a two- to threefold higher odds of developing incident AF as it related to baseline CSA.56 According to these data, CSA may pose a greater risk for development of AF than OSA.

With respect to AF after cardiac surgery, patients with sleep apnea and obesity appear to be at higher risk for developing AF as measured by the apnea–hypopnea index and oxygen desaturation index.57

Treatment of sleep apnea may improve arrhythmic burden. Case-based studies have shown reduced burden and resolution of baseline arrhythmia with CPAP treatment for OSA as therapeutic pressure was achieved.58 Another case-based study involved an individual with snoring and OSA and AF at baseline.59 Several retrospective studies have shown that treatment of OSA after ablation and after cardioversion results in reduced recurrence of AF; however, large definitive clinical trials are lacking.

Stroke

Sleep apnea is a risk factor for stroke due to intermittent hypoxia-mediated elevation of oxidative stress and systemic inflammation, hypercoaguability, and impairment of cerebral autoregulation.60 However, the relationship may be bidirectional in that stroke may be a risk factor for sleep apnea in the post-stroke period. The prevalence of sleep apnea post-stroke has been reported to be up to 70%. CSA can occur in up to 26% during the post-stroke phase.61 Data are inconsistent in terms of the location and size of stroke and the risk of sleep apnea, though cerebrovascular neuronal damage to the brainstem and cortical areas are evident.62 In one study, the incidence of stroke appeared to increase with the severity of sleep apnea.63 These findings were more pronounced in men than in women; however, this study may not have captured the increased cardiovascular risk in postmenopausal women. The Outcomes of Sleep Disorders in Older Men study found that severe hypoxia increased the incidence of stroke, and that hypoxia may be a predictor of newly diagnosed stroke in older men.64 Although definitive clinical trials are underway, post-hoc propensity-score matched analysis from the Sleep Apnea Cardiovascular Endpoints (SAVE) study showed a lower stroke risk in those adherent to CPAP compared with the control group (HR=0.56, 95% CI: 0.30-0.90).65