Laboratory tests in rheumatology: A rational approach

Release date: March 1, 2019

Expiration date: February 29, 2020

Estimated time of completion: 1 hour

Click here to start this CME/MOC activity.

ABSTRACT

Laboratory tests are useful in diagnosing rheumatic diseases, but clinicians should be aware of the limitations of these tests. This article uses case vignettes to provide practical and evidence-based guidance on requesting and interpreting selected tests, including rheumatoid factor, anticitrullinated peptide antibody, antinuclear antibody, antiphospholipid antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, and human leukocyte antigen-B27.

KEY POINTS

- If a test was requested without a clear indication and the result is positive, it is important to bear in mind the potential pitfalls associated with that test; immunologic tests have limited specificity.

- A positive rheumatoid factor or anticitrullinated peptide antibody test can help diagnose rheumatoid arthritis in a patient with early polyarthritis.

- A positive HLA-B27 test can help diagnose ankylosing spondylitis in patients with inflammatory back pain and normal imaging.

- Positive antinuclear cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) can help diagnose ANCA-associated vasculitis in a patient with glomerulonephritis.

- A negative antinuclear antibody test reduces the likelihood of lupus in a patient with joint pain.

HUMAN LEUKOCYTE ANTIGEN-B27

A 22-year-old man presents to his primary care physician with a 4-month history of gradually worsening low back pain associated with early morning stiffness lasting more than 2 hours. He has no peripheral joint symptoms.

In the last 2 years, he has had 2 separate episodes of uveitis. There is a family history of ankylosing spondylitis in his father. Examination reveals global restriction of lumbar movements but is otherwise unremarkable. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine and sacroiliac joints is normal.

Should this patient be tested for human leukocyte antigen-B27 (HLA-B27)?

,The major histocompatibility complex (MHC) is a gene complex that is present in all animals. It encodes proteins that help with immunologic tolerance. HLA simply refers to the human version of the MHC.53 The HLA gene complex, located on chromosome 6, is categorized into class I, class II, and class III. HLA-B is one of the 3 class I genes. Thus, a positive HLA-B27 result simply means that the particular gene is present in that person.

HLA-B27 is strongly associated with ankylosing spondylitis, also known as axial spondyloarthropathy.54 Other genes also contribute to the pathogenesis of ankylosing spondylitis, but HLA-B27 is present in more than 90% of patients with this disease and is by far considered the most important. The association is not as strong for peripheral spondyloarthropathy, with studies reporting a frequency of up to 75% for reactive arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease-associated arthritis, and up to 50% for psoriatic arthritis and uveitis.55

About 9% of healthy, asymptomatic individuals may have HLA-B27, so the mere presence of this gene is not evidence of disease.56 There may be up to a 20-fold increased risk of ankylosing spondylitis among those who are HLA-B27-positive.57

Some HLA genes have many different alleles, each of which is given a number (explaining the number 27 that follows the B). Closely related alleles that differ from one another by only a few amino-acid substitutions are then categorized together, thus accounting for more than 100 subtypes of HLA-B27 (designated from HLA-B*2701 to HLA-B*27106). These subtypes vary in frequency among different racial groups, and the population prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis parallels the frequency of HLA-B27.58 The most common subtype seen in white people and American Indians is B*2705. HLA-B27 is rare in blacks, explaining the rarity of ankylosing spondylitis in this population. Further examples include HLA-B*2704, which is seen in Asians, and HLA-B*2702, seen in Mediterranean populations. Not all subtypes of HLA-B27 are associated with disease, and some, like HLA-B*2706, may also be protective.

When should the clinician consider testing for HLA-B27?

Peripheral spondyloarthropathy may present with arthritis, enthesitis (eg, heel pain due to inflammation at the site of insertion of the Achilles tendon or plantar fascia), or dactylitis (“sausage” swelling of the whole finger or toe due to extension of inflammation beyond the margins of the joint). Other clues may include psoriasis, inflammatory bowel disease, history of preceding gastrointestinal or genitourinary infection, family history of similar conditions, and history of recurrent uveitis.

For the initial assessment of patients who have inflammatory back pain, plain radiography of the sacroiliac joints is considered the gold standard.59 If plain radiography does not show evidence of sacroiliitis, MRI of the sacroiliac joints should be considered. While plain radiography can reveal only structural changes such as sclerosis, erosions, and ankylosis, MRI is useful to evaluate for early inflammatory changes such as bone marrow edema. Imaging the lumbar spine is not necessary, as the sacroiliac joints are almost invariably involved in axial spondyloarthropathy, and lesions seldom occur in the lumbar spine in isolation.60

The diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis previously relied on confirmatory imaging features, but based on the new International Society classification criteria,61–63 which can be applied to patients with more than 3 months of back pain and age of onset of symptoms before age 45, patients can be classified as having 1 of the following:

- Radiographic axial spondyloarthropathy, if they have evidence of sacroiliitis on imaging plus 1 other feature of spondyloarthropathy

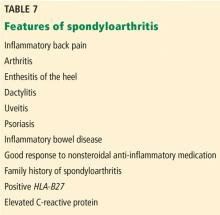

- Nonradiographic axial spondyloarthropathy, if they have a positive HLA-B27 plus 2 other features of spondyloarthropathy (Table 7).

These new criteria have a sensitivity of 82.9% and specificity of 84.4%.62,63 The disease burden of radiographic and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthropathy has been shown to be similar, suggesting that they are part of the same disease spectrum. Thus, the HLA-B27 test is useful to make a diagnosis of axial spondyloarthropathy even in the absence of imaging features and could be requested in patients with 2 or more features of spondyloarthropathy. In the absence of imaging features and a negative HLA-B27 result, however, the patient cannot be classified as having axial spondyloarthropathy.

Back to our patient

The absence of radiographic evidence would not exclude axial spondyloarthropathy in our patient. The HLA-B27 test is requested because of the inflammatory back pain and the presence of 2 spondyloarthropathy features (uveitis and the family history) and is reported to be positive. His disease is classified as nonradiographic axial spondyloarthropathy.

He is started on regular naproxen and is referred to a physiotherapist. After 1 month, he reports significant symptomatic improvement. He asks if he can be retested for HLA-B27 to see if it has become negative. We tell him that there is no point in repeating it, as it is a gene and will not disappear.

SUMMARY: CONSIDER THE CLINICAL PICTURE

When approaching a patient suspected of having a rheumatologic disease, a clinician should first consider the clinical presentation and the intended purpose of each test. The tests, in general, might serve several purposes. They might help to:

Increase the likelihood of the diagnosis in question. For example, a positive rheumatoid factor or anticitrullinated peptide antibody can help diagnose rheumatoid arthritis in a patient with early polyarthritis, a positive HLA-B27 can help diagnose ankylosing spondylitis in patients with inflammatory back pain and normal imaging, and a positive ANCA can help diagnose ANCA-associated vasculitis in a patient with glomerulonephritis.

Reduce the likelihood of the diagnosis in question. For example, a negative antinuclear antibody test reduces the likelihood of lupus in a patient with joint pains.

Monitor the condition. For example DNA antibodies can be used to monitor the activity of lupus.

Plan the treatment strategy. For example, one might consider lifelong anticoagulation if antiphospholipid antibodies are persistently positive in a patient with thrombosis.

Prognosticate. For example, positive rheumatoid factor and anticitrullinated peptide antibody increase the risk of erosive rheumatoid arthritis.

If the test was requested in the absence of a clear indication and the result is positive, it is important to bear in mind the potential pitfalls associated with that test and not attach a diagnostic label prematurely. None of the tests can confirm or exclude a condition, so the results should always be interpreted in the context of the whole clinical picture.