Laboratory tests in rheumatology: A rational approach

Release date: March 1, 2019

Expiration date: February 29, 2020

Estimated time of completion: 1 hour

Click here to start this CME/MOC activity.

ABSTRACT

Laboratory tests are useful in diagnosing rheumatic diseases, but clinicians should be aware of the limitations of these tests. This article uses case vignettes to provide practical and evidence-based guidance on requesting and interpreting selected tests, including rheumatoid factor, anticitrullinated peptide antibody, antinuclear antibody, antiphospholipid antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, and human leukocyte antigen-B27.

KEY POINTS

- If a test was requested without a clear indication and the result is positive, it is important to bear in mind the potential pitfalls associated with that test; immunologic tests have limited specificity.

- A positive rheumatoid factor or anticitrullinated peptide antibody test can help diagnose rheumatoid arthritis in a patient with early polyarthritis.

- A positive HLA-B27 test can help diagnose ankylosing spondylitis in patients with inflammatory back pain and normal imaging.

- Positive antinuclear cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) can help diagnose ANCA-associated vasculitis in a patient with glomerulonephritis.

- A negative antinuclear antibody test reduces the likelihood of lupus in a patient with joint pain.

ANTINUCLEAR ANTIBODY

A 37-year-old woman presents to her primary care physician with the complaint of tiredness. She has a family history of systemic lupus erythematosus in her sister and maternal aunt. She is understandably worried about lupus because of the family history and is asking to be tested for it.

Would testing for antinuclear antibody be reasonable?

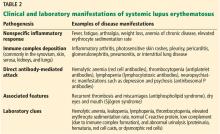

Antinuclear antibody is not a single antibody but rather a family of autoantibodies that are directed against nuclear constituents such as single- or double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid (dsDNA), histones, centromeres, proteins complexed with ribonucleic acid (RNA), and enzymes such as topoisomerase.17,18

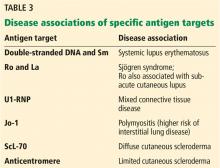

,Protein antigens complexed with RNA and some enzymes in the nucleus are also known as extractable nuclear antigens (ENAs). They include Ro, La, Sm, Jo-1, RNP, and ScL-70 and are named after the patient in whom they were first discovered (Robert, Lavine, Smith, and John), the antigen that is targeted (ribonucleoprotein or RNP), and the disease with which they are associated (anti-ScL-70 or antitopoisomerase in diffuse cutaneous scleroderma).

Antinuclear antibody testing is commonly requested to exclude connective tissue diseases such as lupus, but the clinician needs to be aware of the following points:

Antinuclear antibody may be encountered in conditions other than lupus

These include19:

- Other autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, primary Sjögren syndrome, systemic sclerosis, autoimmune thyroid disease, and myasthenia gravis

- Infection with organisms that share the epitope with self-antigens (molecular mimicry)

- Cancers

- Drugs such as hydralazine, procainamide, and minocycline.

Antinuclear antibody might also be produced by the healthy immune system from time to time to clear the nuclear debris that is extruded from aging cells.

A study in healthy individuals20 reported a prevalence of positive antinuclear antibody of 32% at a titer of 1/40, 15% at a titer of 1/80, 7% at a titer of 1/160, and 3% at a titer of 1/320. Importantly, a positive result was more common among family members of patients with autoimmune connective tissue diseases.21 Hence, a positive antinuclear antibody result does not always mean lupus.

Antinuclear antibody testing is highly sensitive for lupus

With current laboratory methods, antinuclear antibody testing has a sensitivity close to 100%. Hence, a negative result virtually rules out lupus.

Two methods are commonly used to test for antinuclear antibody: indirect immunofluorescence and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).22 While human epithelial (Hep2) cells are used as the source of antigen in immunofluorescence, purified nuclear antigens coated on multiple-well plates are used in ELISA.

Although ELISA is simpler to perform, immunofluorescence has a slightly better sensitivity (because the Hep2 cells express a wide range of antigens) and is still considered the gold standard. As expected, the higher sensitivity occurs at the cost of reduced specificity (about 60%), so antinuclear antibody will also be detected in all the other conditions listed above.23

To improve the specificity of antinuclear antibody testing, laboratories report titers (the highest dilution of the test serum that tested positive); a cutoff of greater than 1/80 is generally considered significant.

Do not order antinuclear antibody testing indiscriminately

To sum up, the antinuclear antibody test should be requested only in patients with involvement of multiple organ systems. Although a negative result would make it extremely unlikely that the clinical presentation is due to lupus, a positive result is insufficient on its own to make a diagnosis of lupus.

Diagnosing lupus is straightforward when patients present with a specific manifestation such as inflammatory arthritis, photosensitive skin rash, hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, or nephritis, or with specific antibodies such as those against dsDNA or Sm. Patients who present with nonspecific symptoms such as arthralgia or tiredness with a positive antinuclear antibody and negative anti-dsDNA and anti-Sm may present difficulties even for the specialist.25–27

Back to our patient

Our patient denies arthralgia. She has no extraarticular symptoms such as skin rashes, oral ulcers, sicca symptoms, muscle weakness, Raynaud phenomenon, pleuritic chest pain, or breathlessness. Findings on physical examination and urinalysis are unremarkable.

Her primary care physician decides to check her complete blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and thyroid-stimulating hormone level. Although she is reassured that her tiredness is not due to lupus, she insists on getting an antinuclear antibody test.

Her complete blood cell counts are normal. Her erythrocyte sedimentation rate is 6 mm/hour. However, her thyroid-stimulating hormone level is elevated, and subsequent testing shows low free thyroxine and positive thyroid peroxidase antibodies. The antinuclear antibody is positive in a titer of 1/80 and negative for anti-dsDNA and anti-ENA.

We explain to her that the positive antinuclear antibody is most likely related to her autoimmune thyroid disease. She is referred to an endocrinologist.