Laboratory tests in rheumatology: A rational approach

Release date: March 1, 2019

Expiration date: February 29, 2020

Estimated time of completion: 1 hour

Click here to start this CME/MOC activity.

ABSTRACT

Laboratory tests are useful in diagnosing rheumatic diseases, but clinicians should be aware of the limitations of these tests. This article uses case vignettes to provide practical and evidence-based guidance on requesting and interpreting selected tests, including rheumatoid factor, anticitrullinated peptide antibody, antinuclear antibody, antiphospholipid antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, and human leukocyte antigen-B27.

KEY POINTS

- If a test was requested without a clear indication and the result is positive, it is important to bear in mind the potential pitfalls associated with that test; immunologic tests have limited specificity.

- A positive rheumatoid factor or anticitrullinated peptide antibody test can help diagnose rheumatoid arthritis in a patient with early polyarthritis.

- A positive HLA-B27 test can help diagnose ankylosing spondylitis in patients with inflammatory back pain and normal imaging.

- Positive antinuclear cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) can help diagnose ANCA-associated vasculitis in a patient with glomerulonephritis.

- A negative antinuclear antibody test reduces the likelihood of lupus in a patient with joint pain.

ANTINEUTROPHIL CYTOPLASMIC ANTIBODY

A 34-year-old man who is an injecting drug user presents with a 2-week history of fever, malaise, and generalized arthralgia. There are no localizing symptoms of infection. Notable findings on examination include a temperature of 38.0°C (100.4°F), needle track marks in his arms, nonblanching vasculitic rash in his legs, and a systolic murmur over the precordium.

His white blood cell count is 15.3 × 109/L (reference range 3.7–11.0), and his C-reactive protein level is 234 mg/dL (normal < 3). Otherwise, results of blood cell counts, liver enzyme tests, renal function tests, urinalysis, and chest radiography are normal.

Two sets of blood cultures are drawn. Transthoracic echocardiography and the antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) test are requested, as are screening tests for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C.

,Was the ANCA test indicated in this patient?

ANCAs are autoantibodies against antigens located in the cytoplasmic granules of neutrophils and monocytes. They are associated with small-vessel vasculitides such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), and isolated pauciimmune crescentic glomerulonephritis, all collectively known as ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV).39

Laboratory methods to detect ANCA include indirect immunofluorescence and antigen-specific enzyme immunoassays. Indirect immunofluorescence only tells us whether or not an antibody that is targeting a cytoplasmic antigen is present. Based on the indirect immunofluorescent pattern, ANCA can be classified as follows:

- Perinuclear or p-ANCA (if the targeted antigen is located just around the nucleus and extends into it)

- Cytoplasmic or c-ANCA (if the targeted antigen is located farther away from the nucleus)

- Atypical ANCA (if the indirect immunofluorescent pattern does not fit with either p-ANCA or c-ANCA).

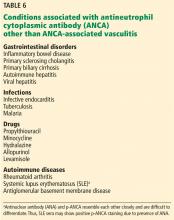

Indirect immunofluorescence does not give information about the exact antigen that is targeted; this can only be obtained by performing 1 of the antigen-specific immunoassays. The target antigen for c-ANCA is usually proteinase-3 (PR3), while that for p-ANCA could be myeloperoxidase (MPO), cathepsin, lysozyme, lactoferrin, or bactericidal permeability inhibitor. Anti-PR3 is highly specific for GPA, while anti-MPO is usually associated with MPA and EGPA. Less commonly, anti-PR3 may be seen in patients with MPA and anti-MPO in those with GPA. Hence, there is an increasing trend toward classifying ANCA-associated vasculitis into PR3-associated or MPO-associated vasculitis rather than as GPA, MPA, EGPA, or renal-limited vasculitis.40

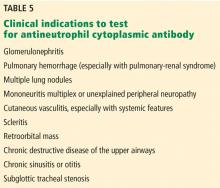

Several audits have shown that the ANCA test is widely misused and requested indiscriminately to rule out vasculitis. This results in a lower positive predictive value, possible harm to patients due to increased false-positive rates, and increased burden on the laboratory.41–43 At least 2 separate groups have demonstrated that a gating policy that refuses ANCA testing in patients without clinical evidence of systemic vasculitis can reduce the number of inappropriate requests, improve the diagnostic yield, and make it more clinically relevant and cost-effective.44,45

The clinician should bear in mind that:

Current guidelines recommend using one of the antigen-specific assays for PR3 and MPO as the primary screening method.48 Until recently, indirect immunofluorescence was used to screen for ANCA-associated vasculitis, and positive results were confirmed by ELISA to detect ANCAs specific for PR3 and MPO,49 but this is no longer recommended because of recent evidence suggesting a large variability between the different indirect immunofluorescent methods and improved diagnostic performance of the antigen-specific assays.

In a large multicenter study by Damoiseaux et al, the specificity with the different antigen-specific immunoassays was 98% to 99% for PR3-ANCA and 96% to 99% for MPO-ANCA.50

ANCA-associated vasculitis should not be considered excluded if the PR3 and MPO-ANCA are negative. In the Damoiseaux study, about 11% to 15% of patients with GPA and 8% to 24% of patients with MPA tested negative for both PR3 and MPO-ANCA.50

If the ANCA result is negative and clinical suspicion for ANCA-associated vasculitis is high, the clinician may wish to consider requesting another immunoassay method or indirect immunofluorescence. Results of indirect immunofluorescent testing results may be positive in those with a negative immunoassay, and vice versa.

Thus, the ANCA result should always be interpreted in the context of the whole clinical picture.51 Biopsy should still be considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of ANCA-associated vasculitis. The ANCA titer can help to improve clinical interpretation, because the likelihood of ANCA-associated vasculitis increases with higher levels of PR3 and MPO-ANCA.52

Back to our patient

Our patient’s blood cultures grow methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus in both sets after 48 hours. Transthoracic echocardiography reveals vegetations around the tricuspid valve, with no evidence of valvular regurgitation. The diagnosis is right-sided infective endocarditis. He is started on appropriate antibiotics.

Tests for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C are negative. The ANCA test is positive for MPO-ANCA at 28 IU/mL (normal < 10).

The positive ANCA is thought to be related to the infective endocarditis. His vasculitis is most likely secondary to infective endocarditis and not ANCA-associated vasculitis. The ANCA test need not have been requested in the first place.