Hepatitis B treatment: Current best practices, avoiding resistance

ABSTRACT

All patients who are positive for hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA should be considered for antiviral treatment. Potency in suppressing HBV DNA is the main factor in the choice of first-line therapy; entecavir and tenofovir constitute the most potent nucleoside and nucleotide analogues to date with the lowest rates of resistance. Viral negativity may reduce the development of liver failure and the need for transplant, although these benefits need to be demonstrated prospectively. Loss of hepatitis B surface antigen, or seroconversion, may represent a new treatment paradigm. The development of resistance to therapy can result in virologic breakthrough and serious clinical consequences. Use of the most potent agents as first-line therapy lowers the risk of resistance; but if resistance develops, adding an additional agent, rather than switching to another therapy, is advised.

KEY POINTS

- Consider treatment for chronic HBV infection for all patients who are positive for HBV DNA, as viral load levels as low as 300 copies/mL confer a risk for hepatocellular carcinoma.

- The goal of therapy is an undetectable level of HBV DNA; initiate therapy with the most potent agent to limit the possibility of resistance.

- Preventing resistance to therapy is crucial for successful treatment of chronic HBV infection.

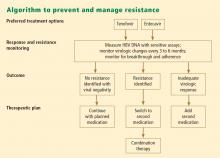

PREVENTING AND MANAGING RESISTANCE

Antiviral drug resistance has a negative impact on the treatment of patients with chronic HBV infection. The development of resistance can result in virologic breakthrough (a confirmed 1 log10 increase in plasma HBV DNA levels)1; increased ALT levels1,39; and the progression of liver disease,40 including hepatic decompensation, development of HCC, and need for liver transplant. In addition, resistance mutations may re-emerge, with covalently closed circular DNA representing a genetic archive for development of resistance; this can significantly limit future treatment options.41 Early detection and regular monitoring are critical to prevention and management of resistance.

Detection

Detecting virologic breakthrough as early as possible increases the likelihood of achieving virologic response. In a study by Rapti and colleagues,42 patients with lamivudine-resistant chronic HBV were treated with a combination of lamivudine and adefovir. The 3-year cumulative probability of virologic response (< 103 copies/mL) was 99% with the addition of adefovir when baseline viral load levels were less than 5 log10 copies/mL, but only 71% when baseline viral loads were greater than 6 log10 copies/mL.

Monitoring

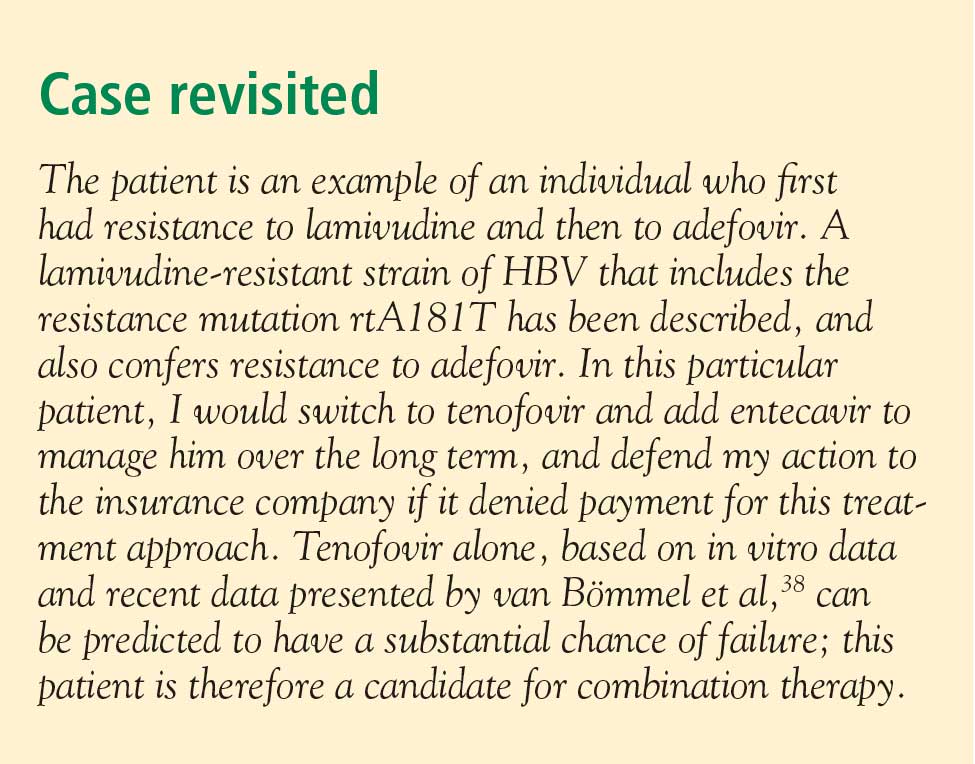

Patient response must be defined correctly. In adherent patients who show an early favorable response to therapy, I advise HBV DNA testing every 3 to 6 months. For those whose response flattens and whose viral load remains high, switching therapy or adding on should be considered. We continue therapy and monitor regularly after HBV DNA reaches an undetectable level. If the response is suboptimal, the treatment regimen is adapted by adding a new agent or switching to an alternative therapy (see “Case revisited”).

For patients who are being treated with tenofovir or entecavir, I typically extend the interval of measuring DNA levels to every 6 months because rates of resistance with these agents are low. If response is suboptimal but resistance is absent, I consider switching to the opposite drug. In those patients with a resistance mutation, I add the other agent.

Managing resistance

Combination therapy has a role in individuals in whom medication has failed to suppress viral load, in the setting of drug resistance, after liver transplant, and in individuals coinfected with HIV (see “Strategies for managing coinfection with hepatitis B virus and HIV”). If patients demonstrate resistance to their current therapy, we examine viral factors, adherence to therapy, and medication availability (eg, cost and insurance coverage). Switching to entecavir in adefovir-resistant patients produces profound suppression of HBV DNA. Patients in whom entecavir or lamivudine have failed may respond to tenofovir, depending on the resistance mutations.

A POTENTIAL FUTURE OPTION

Clevudine is a nucleoside analogue in phase 3 clinical studies in the United States. Its potential role in therapy is not yet clear. To be determined is whether it will induce a long-term, off-treatment viral response, in which case treatment may be able to be terminated earlier, and whether it will show clinically important cross-resistance with other nucleoside analogues. The availability of more sensitive assays to demonstrate the emergence of early viral resistance would enable earlier changes in treatment for more successful outcomes.

SUMMARY

Preventing resistance is crucial to the success of antiviral drug therapy for treatment of chronic HBV; a persistently high viral load increases the risk of cirrhosis and HCC, and resistance is associated with increased HBV DNA levels. The best chance for long-term success depends on initiating therapy before cirrhosis develops, when viral load is still low; profound suppression of viral load using the most potent agents as first-line therapy; and long-term monitoring of HBV DNA. The development of resistance can result in virologic breakthrough and liver complications. Entecavir and tenofovir represent the most effective first-line options to suppress HBV DNA. Because cross-resistance can occur, adding another agent is preferred to switching agents if resistance to initial therapy develops.