Hepatitis B treatment: Current best practices, avoiding resistance

ABSTRACT

All patients who are positive for hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA should be considered for antiviral treatment. Potency in suppressing HBV DNA is the main factor in the choice of first-line therapy; entecavir and tenofovir constitute the most potent nucleoside and nucleotide analogues to date with the lowest rates of resistance. Viral negativity may reduce the development of liver failure and the need for transplant, although these benefits need to be demonstrated prospectively. Loss of hepatitis B surface antigen, or seroconversion, may represent a new treatment paradigm. The development of resistance to therapy can result in virologic breakthrough and serious clinical consequences. Use of the most potent agents as first-line therapy lowers the risk of resistance; but if resistance develops, adding an additional agent, rather than switching to another therapy, is advised.

KEY POINTS

- Consider treatment for chronic HBV infection for all patients who are positive for HBV DNA, as viral load levels as low as 300 copies/mL confer a risk for hepatocellular carcinoma.

- The goal of therapy is an undetectable level of HBV DNA; initiate therapy with the most potent agent to limit the possibility of resistance.

- Preventing resistance to therapy is crucial for successful treatment of chronic HBV infection.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Nucleoside analogues

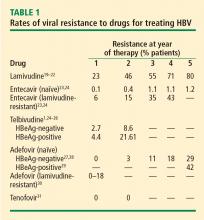

Lamivudine. The incidence of lamivudine resistance increases with increased treatment duration, reaching a peak of 80% after 5 years of treatment19–22; use of this agent eventually requires combination therapy. For this reason, lamivudine is considered a third-line drug and is not recommended as a first-line therapy.

Entecavir. Entecavir induces profound suppression of HBV DNA (to undetectable levels by weeks 24 to 36) in patients who are HBeAg positive or negative, regardless of baseline HBV DNA levels; resistance rates are very low in treatment-naïve patients,23 and entecavir is therefore considered first-line therapy. More than 90% of HBeAg-positive or -negative patients who are adherent to entecavir are HBV DNA negative at 5 years.24 Loss of HBsAg is 5% in entecavir-treated patients at follow-up of approximately 80 weeks, which is roughly double the rate of HBsAg loss with lamivudine.32

Telbivudine. Telbivudine has a secondary role in treatment of HBV infection. In a study by Lai et al,25,26 the cumulative incidence of telbivudine resistance and virologic breakthrough in HBeAg-positive patients rose from nearly 5% after 1 year to 22% after 2 years of treatment. Although the incidence was lower in HBeAg-negative patients, rates of genotypic resistance with virologic breakthrough rose to 9% in this population.

Since these results report genotypic resistance and virologic breakthrough, the rates of genotypic resistance in these patients may actually be higher than reported. Indeed, genotypic resistance was detected in 6.8% of the entire study population after 1 year of treatment. In this study, it must be remembered that patients with HBV DNA levels that were detectable by PCR (≥ 300 copies/mL) but were less than 1,000 copies/mL were not assessed for resistance.

Because of high rates of resistance associated with telbivudine, its role in the treatment of chronic HBV is secondary. I may use it in pregnant patients because most other nucleoside analogues are category C drugs and telbivudine is a category B agent (see “Management of hepatitis B in pregnancy: Weighing the options”). There are risks of myositis and neuropathy with telbivudine; although these risks are low, I mention them to patients when discussing a treatment plan.

Nucleotide analogues

Adefovir. Adefovir is considered second-line or add-on therapy when resistance to lamivudine develops because of its low potency in suppressing viral load. At 48 weeks, only 12% of HBeAg-positive patients are HBV DNA negative when treated with adefovir monotherapy.33,34

In a phase 3 clinical trial, genotypic resistance to adefovir was detected in 29% of HBeAg-negative patients treated for up to 5 years.27 The probability of resistance with virologic breakthrough was 3%, 8%, 14%, and 20% after 2, 3, 4, and 5 years of treatment, respectively.

In patients infected with lamivudine-resistant HBV, the probability of adefovir resistance is reduced by adding adefovir to ongoing lamivudine therapy, according to data from a large retrospective comparative study.35 In patients treated with adefovir monotherapy, the probability of virologic breakthrough (defined as > 1 log10 rebound in HBV DNA compared with on-treatment nadir) reached 30% over 36 months. In patients treated with add-on adefovir, the probability of virologic breakthrough was reduced to 6%. Similarly, the probability of adefovir resistance over 36 months of treatment was greater in the adefovir monotherapy group (16%) than in the add-on adefovir group (0%).

Although adefovir resistance is observed infrequently when adefovir is added to lamivudine, the effectiveness of adding adefovir is still limited by its low potency.

Tenofovir. More than 90% of HBeAg-negative patients and nearly 80% of HBeAg-positive patients treated with tenofovir have persistent virologic responses and HBV DNA levels less than 400 copies/mL by 72 weeks, with minimal side effects.33,34 Marcellin et al reported no development of resistance to tenofovir after 48 weeks of treatment.31 Although the nucleotide analogues have been associated with renal toxicity,36 the risk of renal toxicity associated with tenofovir is 1% or less per year; it can be reduced even further by calculating renal function through the use of the Cockroft-Gault equation or the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation prior to therapy and adjusting the dosage accordingly.37

With profound HBV DNA suppression, HBsAg loss occurs in about 5% of tenofovir-treated patients at 64 weeks.33

Treatment with tenofovir in treatment-experienced patients leads to potent suppression of HBV DNA independent of HBV genotype, HBV mutations (YMDD mutations) that signal lamivudine resistance, or HBeAg status at baseline.38 Patients with genotypic resistance to adefovir at baseline had a lower probability of achieving HBV DNA suppression during treatment with tenofovir.

Pegylated interferon

Pegylated interferon has proven useful in subsets of HBV DNA–positive patients. These include patients with genotype A or B who are young, those with high ALT levels (≥ 2 or 3 times the upper limit of normal) and low viral load (< 107 copies/mL), and patients without significant comorbidities.6 Pegylated interferon is also an option for patients who require a defined treatment period (eg, a woman wishing to become pregnant in 1 to 2 years). The patients who would benefit from pegylated interferon as first-line therapy must be better defined, and early markers of virologic response need to be identified.