Diabetes with obesity—Is there an ideal diet?

ABSTRACT

For individuals who are overweight or obese, weight loss is effective in preventing and improving the management of type 2 diabetes. Together with other lifestyle factors like exercise and behavior modification, diet plays a central role in achieving weight loss. Diets vary based on the type and amount of carbohydrate, fat, and protein consumed to meet daily caloric intake goals. A number of popular diets are reviewed as well as studies evaluating the effect of various diets on weight loss, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors. Current trends favor the low-carbohydrate, low-glycemic index, Mediterranean, and very-low-calorie diets. However, no optimal dietary strategy exists for patients with obesity and diabetes, and more research is needed. Given the wide range of dietary choices, the best diet is one that achieves the best adherence based on the patient’s dietary preferences, energy needs, and health status.

KEY POINTS

- Weight loss in individuals who are obese has been shown to be effective in the prevention and management of type 2 diabetes.

- Diets vary based on the type and amount of carbohydrate, fat, and protein consumed to meet daily caloric intake goals.

- Diets of equal caloric intake result in similar weight loss and glucose control regardless of the macronutrient content.

- The metabolic status of the patient based on lipid profiles and renal and liver function is the main determinant for the macronutient composition of the diet.

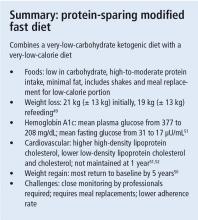

PROTEIN-SPARING MODIFIED FAST

One of the earlier studies on protein-sparing modified fast showed that weight loss was as high as 21 kg ± 13 kg during the initial phase and 19 kg ± 13 kg during the refeeding phase.49 Weight regain is high: in the protein-sparing modified fast, most patients return to their baseline weight in 5 years.50

A study comparing 6 patients who were put on a protein-sparing modified fast diet with 6 patients who underwent gastric bypass surgery showed that the mean steady-state plasma glucose fell from 377 mg/dL to 208 mg/dL (P < .008) and mean fasting insulin values fell from 31.0 to 17.0 µU/mL (P < .004).51 There were also changes in cardiovascular risk factors: mean HDL-C values increased from 33.8 mg/dL to 40.5 mg/dL (P < .008), and factor VIII coagulant activity decreased from 194% to 140% (P < .005).51 Total cholesterol and LDL-C levels were also improved, but these changes were not always maintained at follow-up visits.52

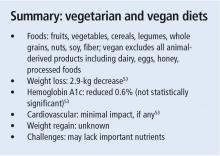

VEGETARIAN AND VEGAN DIETS

In 2013, Mishra et al53 conducted a randomized clinical trial of employees with obesity and type 2 DM (N = 291) assigned to a low-fat vegan diet or no intervention for 18 weeks. Weight decreased in the low-fat vegan diet group compared with the control group (2.9 kg vs 0.06 kg, respectively, P < .001). Statistically significant reductions in total cholesterol (8 mg/dL vs 0.01 mg/dL, P < .01), LDL-C (8.1 mg/dL vs 0.9 mg/dL, P < .01), and HbA1c (0.6% vs 0.08%, P < .01) occurred in the intervention group compared with the control group.53

Many studies of vegetarian and vegan diets have been of short duration and used a combination of low-fat and vegetarian or vegan diets on people that were not all considered obese. Research is limited for vegan and vegetarian diets, and not enough information exists about the effects on glycemic control and cardiovascular risk. Vegan and vegetarian diets may reduce the intake of many essential nutrients. Vegans who exclude dairy products, for example, have low bone mineral density and higher risk of fractures due to inadequate intake of calcium.

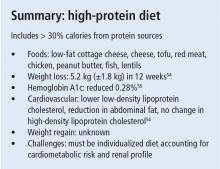

HIGH-PROTEIN DIET

Parker et al54 reported a weight loss of 5.2 kg ± 1.8 kg in 12 weeks in 54 patients with obesity and type 2 DM irrespective of a diet with high or low protein content. Women on a high-protein diet lost more total fat and abdominal fat compared with women on a low-protein diet. Total lean mass decreased in all patients irrespective of diet.

Studies have shown that high-protein diets can improve glucose control. Ajala et al55 reviewed 20 clinical trials of patients with type 2 DM randomized to various diets for more than 6 months. In the trials that used a high-protein diet as an intervention, HbA1c levels decreased as much as 0.28% compared with the control diets (P < .001). A small study of 8 men with untreated type 2 DM compared a high-protein low-carbohydrate diet (nonketogenic, protein 30%, carbohydrate content 20%, fat 50%) with a control diet (protein 15%, carbohydrate 55%, fat 30%).56 The high-protein low-carbohydrate diet group had lower HbA1c levels (7.6 mg/dL ± 0.3 mg/dL vs 9.8 mg/dL ± 0.5 mg/dL) and mean 24-hour integrated serum glucose (126 mg/dL vs 198 mg/dL) compared with the control diet. Most of the studies of high-protein diets have been small and of short duration, and have used a combination of macronutrients (high protein and low carbohydrate), limiting the ability to identify the dietary component that had the most effect.

There are no studies evaluating cardiovascular outcomes, but some studies have included cardiovascular risk factors such as LDL-C levels and body fat composition. Parker et al54 showed that women on a high-protein diet lost more total fat (5.3 kg vs 2.8 kg, P = .009) and abdominal fat (1.3 kg vs 0.7 kg, P = .006) compared with a low-protein diet. Interestingly, no difference in total fat and abdominal fat was found in men. LDL-C reduction was greater in a high-protein diet compared with a low-protein diet (5.7% vs 2.7%, P < .01).54 In a review by Ajala et al,55 the high-protein diet was the only diet that did not show a rise in HDL-C levels after interventions of more than 6 months.

The ADA does not recommend high-protein diets as a method for weight loss because the long-term effects are unknown. ADA recommendations include an individualized approach based on a patient’s cardiometabolic risk and renal profiles. Protein content should be 0.8 g/kg to 1.0 g/kg of weight per day in patients with early chronic kidney disease, and 0.8 g/kg of weight per day in patients with advanced kidney disease.6

COMPARISONS AMONG DIETS

Studies comparing diets have reached varying conclusions and have been limited by inconsistent diet definitions, small sample sizes, and high participant dropout rates. A meta-analysis conducted by Ajala et al55 included 20 randomized controlled trials that lasted 6 months or more with 3,073 individuals in the analysis. Low-carbohydrate, vegetarian, vegan, low-glycemic, high-fiber, Mediterranean, and high-protein diets were compared with low-fat, high-glycemic, ADA, European Association for the Study of Diabetes, and low-protein diets as controls. The greatest weight loss occurred with the low-carbohydrate (−0.69 kg, P = .21) and Mediterranean diets (−1.84 kg, P < .001). Compared with the control diets, the greatest reductions in HbA1c were with the low-carbohydrate (−0.12%, P = .04), low-glycemic (−0.14%, P = .008), Mediterranean (−0.47%, P < .001), and high-protein diets (−0.28%, P < .001). HDL-C levels increased in all the diets except the high-protein diet.55

CONCLUSION

The optimal macronutrient intake for patients with obesity and type 2 DM is unknown. Diets with equivalent caloric intakes result in similar weight loss and glucose control regardless of the macronutrient contents. It is important that total caloric intake be appropriate for weight management and glucose control goals. The metabolic status of the patient as determined by lipid profiles, and renal and liver function is the main driver for the macronutrient composition of the diet.

Current trends favor the low-carbohydrate, low-glycemic, Mediterranean, and low-caloric intake diets, though there is no evidence that one is best for weight loss and optimal glycemic control in patients with obesity and type 2 DM. Studies are limited by varying definitions, high dropout rates, and poor adherence. In addition, for many patients, weight regain often follows successful short-term weight loss, indicative of a low durability of results with many diet interventions. Medical nutrition therapy and a multidisciplinary lifestyle approach remain essential components in managing weight and type 2 DM. The ideal diet is one that achieves the best adherence when tailored to a patient’s preferences, energy needs, and health status.