Diabetes with obesity—Is there an ideal diet?

ABSTRACT

For individuals who are overweight or obese, weight loss is effective in preventing and improving the management of type 2 diabetes. Together with other lifestyle factors like exercise and behavior modification, diet plays a central role in achieving weight loss. Diets vary based on the type and amount of carbohydrate, fat, and protein consumed to meet daily caloric intake goals. A number of popular diets are reviewed as well as studies evaluating the effect of various diets on weight loss, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors. Current trends favor the low-carbohydrate, low-glycemic index, Mediterranean, and very-low-calorie diets. However, no optimal dietary strategy exists for patients with obesity and diabetes, and more research is needed. Given the wide range of dietary choices, the best diet is one that achieves the best adherence based on the patient’s dietary preferences, energy needs, and health status.

KEY POINTS

- Weight loss in individuals who are obese has been shown to be effective in the prevention and management of type 2 diabetes.

- Diets vary based on the type and amount of carbohydrate, fat, and protein consumed to meet daily caloric intake goals.

- Diets of equal caloric intake result in similar weight loss and glucose control regardless of the macronutrient content.

- The metabolic status of the patient based on lipid profiles and renal and liver function is the main determinant for the macronutient composition of the diet.

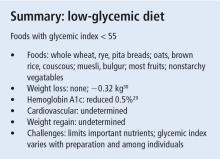

LOW-GLYCEMIC DIET

Various factors affect the GI including the type of carbohydrate, fat content, protein content, and acidity of the food consumed, as well as the rate of intestinal reaction to the food. The faster the digestion of a food, the higher the GI. High-GI foods (> 70), such as those highly processed and with high starch content, produce higher peak glucose levels when compared with low-GI foods (< 55). Low-GI foods include lentils, beans, oats, and nonstarchy vegetables.

Low-GI foods curb the large and rapid rise of blood glucose, insulin response, and glucagon inhibition that occur with high-GI foods. Many low-GI foods have high amounts of fiber, which prolongs distention of the gastrointestinal tract, increases secretion of cholecystokinin and incretins, and extends statiety.28

In a meta-analysis of 19 randomized trials of overweight or obese patients (BMI > 25), a low-glycemic diet did not show weight loss when compared with an isocaloric control diet (mean difference −0.32 kg; 95% confidence interval [CI] −0.86 kg, 0.23 kg).29 On the other hand, the effect on glycemic control is more pronounced. Another meta-analysis that included 11 studies of patients with DM who followed a low-glycemic diet for less than 3 months to over 6 months showed that those who followed a low-glycemic diet had a significant reduction of HbA1c (6 studies had HbA1c as the primary outcome, HbA1c weighted mean difference −0.5%; 95% CI, −0.8 to −0.2; P = .001). Five studies reported on parameters related to insulin action, and 1 showed increased sensitivity measured by euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp in a low-glycemic diet (glucose disposal 7.0 ± 1.3 mg glucose/kg/min) vs a high-glycemic diet (4.8 mg glucose/kg/min ± 0.9, P < .001).28

There are no large trials of cardiovascular mortality or morbidity of low-glycemic diets, but some studies have included cardiovascular parameters. A randomized study of 210 patients with type 2 DM evaluated cardiovascular risk factors after 6 months of a low-glycemic diet and high-glycemic diet. The low-glycemic diet group had an increase in HDL-C compared with the high-glycemic diet group (1.7 mg/dL; 95% CI, 0.8 to 2.6 mg/dL vs −0.2 mg/dL; 95% CI, −0.9 to –0.5 mg/dL, P = .005).30 Another crossover study of 20 patients with type 2 DM on a low-glycemic diet over 2 consecutive 24-day periods revealed a 53% reduction of the activity of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, a thrombolytic factor that increases plaque formation.31 Most studies were of short duration; thus, weight regain was not clearly established.

The GI of low-GI foods differs based on the cooking method, presence of other macronutrients, and metabolic variations among individuals. Low-glycemic diets can reduce the intake of important dietary nutrients. The ADA notes that low-glycemic diets may provide only modest benefit in controlling postprandial hyperglycemia.32

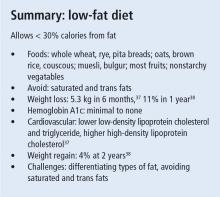

LOW-FAT DIET

Different types of fats have different effects on metabolism. LDL-C is mostly derived from saturated fats.34 Consuming 2% of energy intake from trans fat substantially increases the risk of coronary heart disease.35 Though the ideal total amount of fat for people with diabetes is unknown, the amount consumed still has important consequences, especially since patients with type 2 DM are at risk for coronary artery disease. The Institute of Medicine states that fat intake of 20% to 35% of energy is acceptable for all adults.16

Low-fat diets along with reduced caloric intake induce weight loss, but this cannot compete with the rapid weight loss that patients experience with the low-carbohydrate diet. This was shown in multiple studies including a meta-analysis of 5 randomized clinical trials of 447 patients with obesity who lost less weight in the low-fat diet group compared with low-carbohydrate diet group (weighted mean difference −3.3 kg; 95% CI, −5.3 to −1.4 kg) at 6 months.36 Interestingly, the difference between diets was nonexistent after 12 months (weighted mean difference −1.0 kg; 95% CI, −3.5 to 1.5 kg), which may be due to weight regain in the low-carbohydrate diet group.36

Foster et al37 studied 307 participants with obesity assigned to a low-fat or low-carbohydrate diet. Both groups lost 11% in 1 year, and with regain, lost 7% from baseline at 2 years. There was no statistically significant difference between groups during the 2 years, but there was a trend for more weight loss in the low-carbohydrate group in the first 3 months (P = .019).37

The low-fat diet has no to minimal improvement in glycemic control in patients with diabetes and obesity, regardless of the weight loss achieved. However, a low-fat diet is associated with some beneficial effects on cardiovascular risks. Nordmann et al36 found no difference in blood pressure between low-carbohydrate and low-fat diets. The low-fat diet was associated with lower total cholesterol and LDL-C levels (weighted mean difference 5.4 mg/dL [0.14 mmol/L]; 95% CI, 1.2 mg/dL to 10.1 mg/dL [0.03–0.26 mmol/L]).36 Triglyceride and HDL-C levels were more favorably changed in the low-carbohydrate diet (for triglycerides, weighted mean difference −22.1 mg/dL [−0.25 mmol/L]; 95% CI, −38.1 to −5.3 mg/dL [−0.43 to −0.06 mmol/L]; and for HDL-C, weighted mean difference 4.6 mg/dL [0.12 mmol/L]; 95% CI, 1.5 mg/dL to 8.1 mg/dL [0.04–0.21 mmol/L]).36