Diabetes with obesity—Is there an ideal diet?

ABSTRACT

For individuals who are overweight or obese, weight loss is effective in preventing and improving the management of type 2 diabetes. Together with other lifestyle factors like exercise and behavior modification, diet plays a central role in achieving weight loss. Diets vary based on the type and amount of carbohydrate, fat, and protein consumed to meet daily caloric intake goals. A number of popular diets are reviewed as well as studies evaluating the effect of various diets on weight loss, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors. Current trends favor the low-carbohydrate, low-glycemic index, Mediterranean, and very-low-calorie diets. However, no optimal dietary strategy exists for patients with obesity and diabetes, and more research is needed. Given the wide range of dietary choices, the best diet is one that achieves the best adherence based on the patient’s dietary preferences, energy needs, and health status.

KEY POINTS

- Weight loss in individuals who are obese has been shown to be effective in the prevention and management of type 2 diabetes.

- Diets vary based on the type and amount of carbohydrate, fat, and protein consumed to meet daily caloric intake goals.

- Diets of equal caloric intake result in similar weight loss and glucose control regardless of the macronutrient content.

- The metabolic status of the patient based on lipid profiles and renal and liver function is the main determinant for the macronutient composition of the diet.

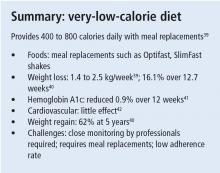

VERY-LOW-CALORIE DIET

Saris et al38 reported results from 8 randomized clinical trials ranging from 10 to 32 patients with obesity comparing very-low-calorie diets with a low-calorie diet of 800 to 1,200 calories a day. Over the first 4 to 6 weeks, weight loss was between 1.4 kg and 2.5 kg per week and was higher with the very-low-calorie diet when compared with the low-calorie diet though not statistically significant. Interestingly, when followed for 16 to 26 weeks, the difference in weight loss was again not statistically significant with no trend for more weight loss in the very-low-calorie diet group. Another meta-analysis looking at 6 randomized clinical trials in patients with obesity showed that weight loss with very-low-calorie diets was statistically significant when compared with low-calorie diets (16.1% ± 1.6% vs 9.7% ± 2.4% weight loss over a period of 12.7 ± 6.4 weeks).39

In general, it is believed that when individuals lose a large amount of weight in a short period, a larger weight regain will occur, resulting in a higher weight than before the initial loss. This was refuted by Tsai et al,39 who found that long-term data (1 to 5 years) showed the percentage of weight regained is higher with a very-low-calorie diet (62%) vs a low-calorie diet (41%) but the overall weight lost remains superior with the very-low-calorie diet, though not statistically significant (6.3% ± 3.2% and 5.0% ± 4.0% loss of initial weight, respectively).

Toubro et al40 looked at 43 obese individuals who followed the very-low-calorie diet for 8 weeks compared with 17 weeks of a conventional diet (1,200 kcal/day) followed by a year of unrestricted calories, low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet or fixed calorie group (1,800 kcal/day). The very-low-calorie diet group lost weight at a more rapid rate, but the rate had no effect on weight maintenance after 6 or 12 months. Interestingly, the group that followed the “unrestricted calories, low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet” for a year maintained 13.2 kg (8.1 kg to 18.3 kg) of the initial 13.8 kg (11.8 kg to 15.7 kg) weight loss, while the fixed-calorie group maintained less weight loss (9.7 kg [6.1 kg to 13.3 kg]). Saris38 concluded that the rapid weight loss by very-low-calorie diet has better long-term results when followed up with a program that includes nutritional education, behavioral therapy, and increased physical activity.

Very-low-calorie diets achieve glycemic control by reducing hepatic glucose output, increasing insulin action in the liver and peripheral tissues, and enhancing insulin secretion. These benefits occur soon after starting the diet, which suggests that caloric restriction plays a critical role. A study at the University of Michigan showed that the use of very-low-calorie diets in addition to moderate-intensity exercise resulted in a reduction of HbA1c from 7.4% (± 1.3%) to 6.5% (± 1.2%) in 66 patients with established type 2 DM.41 HbA1c of less than 7% occurred in 76% of patients with established diabetes and 100% of patients with newly diagnosed diabetes.41 Improvement in HbA1c over 12 weeks was associated with higher baseline HbA1c and greater reduction in BMI.41

Long-term cardiovascular risk reduction of very-low-calorie diets is small. One study showed that serum total cholesterol decreased at 2 weeks but did not differ at 3 months from baseline.42 A large reduction was observed in serum triglycerides at 3 months (4.57 mmol/L ± 1.0 mmol/L vs 2.18 mmol/L ± .26 mmol/L, P = .012) while HDL-C increased (0.96 mmol/L ± .06 mmol/L vs 1.11 mmol/L ± .05 mmol/L, P = .009).42 Blood pressure was also reduced in both systolic pressure (152 mm Hg ± 6 mm Hg vs 133 mm Hg ± 3 mm Hg, P = .004) and diastolic pressure (92 mm Hg ± 3 mm Hg vs 81 mm Hg ± 3 mm Hg, P = .007).42

Challenges with this diet include significant weight regain and safety concerns for patients with obesity and type 2 DM, especially those who are taking insulin, since this diet will lead to significant rapid lowering of insulin levels.38 Finally, very-low-calorie diets require a multidisciplinary approach with frequent health professional visits.

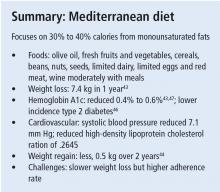

MEDITERRANEAN DIET

This diet also has a positive impact on glycemic control and has been shown to reduce the incidence of diabetes. Estruch et al45 conducted a randomized controlled trial on 772 adults at high risk for cardiovascular disease, of which 421 had type 2 DM, assigned to Mediterranean diet supplemented either with extra-virgin olive oil or mixed nuts compared with a control group receiving advice on a low-fat diet. Their primary prevention trial, PREDIMED, looked mainly at the rate of total cardiovascular events (stroke, myocardial infarction, cardiovascular death); however, a subgroup analysis showed that the incidence of new-onset diabetes was reduced by 52% with the Mediterranean diet compared with the control group after 4 years of follow-up. Multivariate-adjusted hazard ratios of diabetes were 0.49 (0.25–0.97) and 0.48 (0.24–0.96) in the Mediterranean diet supplemented with olive oil and nuts groups, respectively, compared with the control group. Intuitively, they also showed that the higher the adherence, the lower the incidence rate.46 This occurred despite no difference in weight loss between the groups and may indicate that the components of the diet itself could have anti-inflammatory and antioxidative effects. Esposito et al47 showed that after 1 year of intervention in 215 patients with type 2 DM, HbA1c was lower in those assigned to the Mediterranean diet vs those assigned to a low-fat diet (difference: −0.6%; 95% CI, −0.9 to −0.3). Similarly, in a 12-month trial, Elhayany et al43 found a significant difference in the reduction in HbA1c in those on the Mediterranean diet compared with a low-fat diet (0.4%, P = .02).

Many studies have shown a beneficial effect of the Mediterranean diet on cardiovascular health. Estruch et al45 showed that 772 patients (143 with type 2 DM) at high risk of cardiovascular disease who followed a Mediterranean diet with nuts for 3 months had a reduced systolic blood pressure of −7.1 mm Hg (CI, −10.0 mm Hg to −4.1 mm Hg) and reduced HDL-C ratio of −0.26 (CI, −0.42 to −0.10) compared with a low-fat diet. There was also a reduction in fasting plasma glucose of −0.30 mmol/L (CI, −0.58 mmol/L to −0.01 mmol/L).45