Tickborne diseases other than Lyme in the United States

ABSTRACT

Tickborne diseases are increasing in the United States, and the geographic range of tick vectors is expanding. Tickborne diseases are challenging to diagnose, as they present with vague symptoms such as fever, constitutional symptoms, and nonspecific laboratory abnormalities. A high degree of clinical suspicion is required to make a diagnosis, as patients often do not recall a tick bite. The availability of laboratory testing for tickborne diseases is limited, especially in the acute setting. Therefore, if a tickborne disease is suspected, empiric therapy should often be initiated before laboratory confirmation of the disease is available. This article summarizes the most common non-Lyme tickborne diseases in the United States.

KEY POINTS

- Tickborne illnesses should be considered in patients with known or potential tick exposure presenting with fever or vague constitutional symptoms in tick-endemic regions.

- Given that tick-bite history is commonly unknown, absence of a known tick bite does not exclude the diagnosis of a tick-borne illness.

- Starting empiric treatment is usually warranted before the diagnosis of tickborne illness is confirmed.

- Tick avoidance is the most effective measure for preventing tickborne infections.

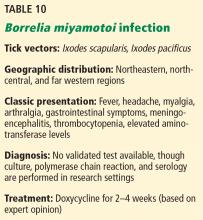

BORRELIA MIYAMOTOI INFECTION

The most common clinical manifestations are similar to other tickborne relapsing fever infections, although a true “relapsing fever” itself is not usually present.53 The characteristic erythema migrans rash often found in Lyme disease is typically absent in B miyamotoi infection; however, when present, it should prompt investigation into coinfection.54 Cases of meningoencephalitis have been reported in immunosuppressed hosts.55

There is currently no validated test available for diagnosis of B miyamotoi; however, PCR and serology are available in a few specialized laboratories.31,53

The treatment of choice is doxycycline for 2 to 4 weeks. Amoxicillin and ceftriaxone also appear effective.53

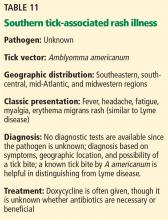

SOUTHERN TICK-ASSOCIATED RASH ILLNESS

Infection can present similarly to Lyme disease with an erythema migrans-like rash and associated flulike symptoms, although systemic symptoms and multiple erythema migrans lesions are less likely with STARI. Also, the erythema migrans-like lesions tend to be smaller and more likely to have central clearing than those in Lyme disease.57 Nevertheless, it is difficult to distinguish the 2 illnesses, especially in mid-Atlantic states such as Maryland or Virginia, where both diseases coexist. The most reliable method of distinguishing STARI from Lyme disease is demonstrating that the patient was bitten by a Lone Star tick rather than an Ixodes tick. Numerous questions remain unanswered about the causative organism, pathophysiology, definitive diagnosis, geographic range of illness, and most effective treatment for STARI.

Most reported cases have responded promptly to doxycycline, though it is not known whether antibiotic treatment is necessary.58

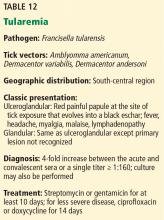

TULAREMIA

Ticks are thought to be the most important vectors, and most cases occur in the south-central United States.59 The geographic distribution of disease is gradually shifting northward due to spread of the major tick vectors, A americanum, D variabilis, and D andersoni. Approximately 100 to 200 cases of tularemia are diagnosed each year in the United States, with most concentrated in Kansas, Oklahoma, Missouri, and Arkansas.60

Humans can acquire F tularensis by several routes, and the route of infection ultimately dictates the clinical syndrome. Ulceroglandular and glandular forms of the disease are the most common in the United States, and both frequently result from a tick bite. A few days after tick exposure, an erythematous, often painful papuloulcerative lesion with a central eschar manifests at the site of the tick bite. Additional symptoms may include fever, chills, headache, myalgia, malaise, and suppurative lymphadenitis.61

Diagnosis can be made by identifying F tularensis in blood, fluid, or tissue culture performed under biosafety level 3 conditions; however, serology is used in most cases.62

Streptomycin and gentamicin are considered drugs of choice and should be continued for at least 10 days. For relatively mild disease, oral doxycycline or ciprofloxacin can be considered for at least 14 days, although the latter is not approved for treatment.59,63

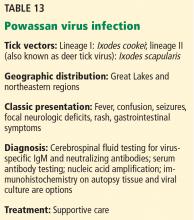

TICKBORNE VIRAL INFECTIONS

Powassan virus, an uncommon flavivirus, is found in the Great Lakes region and northeast United States. In the Great Lakes region, I cookei ticks transmit the traditional lineage of this virus. However, more recent cases have been identified in the Northeast and Midwest, where Powassan virus lineage II (or deer tick virus) is transmitted by I scapularis.31,64

The classic presentation is a viral encephalitis. Rash (most often maculopapular) and gastrointestinal symptoms have been reported as well. A high index of suspicion is needed for diagnosis because clinical features and laboratory findings resemble those of other arboviral infections.

Treatment for Powassan viral encephalitis is supportive, although corticosteroids have been used with some success.64 While asymptomatic infection has been documented, the reported mortality rate of Powassan virus encephalitis is 10% to 15%, and focal neurologic deficits can persist among survivors.65

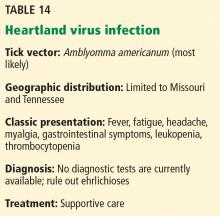

Clinical and laboratory features appear to be very similar to those of the ehrlichioses.1 A clinical diagnosis should be considered in patients with A americanum exposure, fever, and cytopenias who lack PCR or serologic evidence for ehrlichiosis infection or who fail to respond to doxycycline therapy.24

COINFECTION

Some tick vectors transmit more than 1 type of infection, and therefore, coinfection with multiple pathogens may occur. For example, I scapularis transmits Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease), HGA, Babesia microti, B miyamotoi, E muris-like agent, and Powassan virus lineage II, while A americanum transmits HME and Heartland virus.24,26,31,34,36,67 Coinfection may increase the severity of disease, often due to a delay in diagnosis, though more research is needed to understand the clinical manifestations of coinfection.31,35,67

PREVENTION

Unfortunately, there are no available human vaccines for tickborne illnesses in the United States, and the effectiveness of single-dose prophylaxis with doxycycline for non-Lyme infections has not been evaluated.4,7,26

Illness is best prevented by minimizing skin exposure to ticks, use of tick repellents containing DEET, use of long-legged and long-sleeved clothing impregnated with an acaricide such as permethrin, and conducting timely body checks for ticks after potential exposure.1,31,32 Light-colored clothing is suggested, since it allows for better visibility of crawling ticks.4,32 Bathing or showering within 2 hours of tick exposure helps prevent attachment of ticks.4,31,68 If camping outside, use of a bed net is recommended.68

Ticks are most easily removed by grasping the head of the tick as close to the skin surface as possible with fine-tipped tweezers.32,68 Removing or crushing ticks with bare hands should be avoided to prevent potential contamination, and hands should be washed thoroughly after tick removal.1,4

Blood donors are screened for a history of symptomatic tickborne disease; however, asymptomatic donors who are not identified at screening pose the greatest risk to the blood supply. Babesia microti is the most common reported transfusion-transmitted parasite in the United States, and transmission of R rickettsii, A phagocytophilum, and E ewingii have also been reported infrequently.28,40,69 Currently, no test is approved to screen blood for tickborne illnesses, though such a test would help prevent transmission of tickborne illnesses by blood transfusion in areas where these diseases are endemic.40,41

TAKE-HOME POINTS

Tickborne illnesses are increasing throughout the United States as a result of vector expansion and changes in human ecology.

It is essential that primary care clinicians consider tickborne illnesses in the differential diagnosis for any patient presenting with a fever and constitutional symptoms when the cause of symptoms is unclear and tick exposure is possible or known.

All the diseases discussed are nationally notifiable conditions, and confirmed cases should be reported.

Knowledge of the geographic locations of potential exposure is paramount to determining which tickborne infections to consider, and the absence of a tick bite history should not exclude the diagnosis in the correct clinical presentation.

In addition, it is important to recognize the limitations of diagnostic testing for many tickborne infections; empiric treatment is most often warranted before confirming the diagnosis.

Tick avoidance is the most effective way to prevent these often severe infections.