Tickborne diseases other than Lyme in the United States

ABSTRACT

Tickborne diseases are increasing in the United States, and the geographic range of tick vectors is expanding. Tickborne diseases are challenging to diagnose, as they present with vague symptoms such as fever, constitutional symptoms, and nonspecific laboratory abnormalities. A high degree of clinical suspicion is required to make a diagnosis, as patients often do not recall a tick bite. The availability of laboratory testing for tickborne diseases is limited, especially in the acute setting. Therefore, if a tickborne disease is suspected, empiric therapy should often be initiated before laboratory confirmation of the disease is available. This article summarizes the most common non-Lyme tickborne diseases in the United States.

KEY POINTS

- Tickborne illnesses should be considered in patients with known or potential tick exposure presenting with fever or vague constitutional symptoms in tick-endemic regions.

- Given that tick-bite history is commonly unknown, absence of a known tick bite does not exclude the diagnosis of a tick-borne illness.

- Starting empiric treatment is usually warranted before the diagnosis of tickborne illness is confirmed.

- Tick avoidance is the most effective measure for preventing tickborne infections.

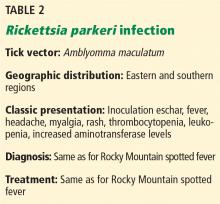

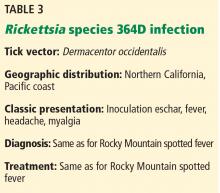

OTHER SPOTTED FEVER GROUP RICKETTSIAl INFECTIONS

Both infections are characterized by an inoculation eschar. Symptoms include fever, headache, myalgia, and regional lymphadenopathy.1 Rash (most often maculopapular or vesicopustular) is characteristic of R parkeri, but it is not common in Rickettsia species 364D rickettsiosis.17,18 Mild thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, and elevated aminotransferase levels are common in R parkeri infection.1 Both infections appear to be milder than RMSF.

EHRLICHIOSES: EHRLICHIOSIS AND ANAPLASMOSIS

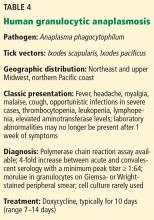

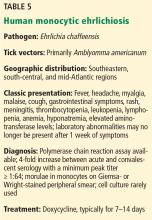

“Ehrlichiosis” is the generic name for infections caused by both the Ehrlichia and Anaplasma genera,19,20 which are small, gram-negative obligate intracellular bacterial pathogens.21 In the United States, infections are most commonly caused by A phagocytophilum, the causative organism of human granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA) (Table 4), and E chaffeensis, the causative organism of human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME) (Table 5). The incidence rates of these 2 infections have increased over the past decade, in part due to increased clinical awareness and improved diagnostic capabilities.3,22,23

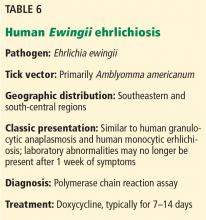

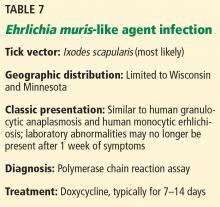

E ewingii (Table 6) and E muris-like agent (Table 7) are lesser known causes of human ehrlichiosis in the United States.20,23–25 Initially, E ewingii was believed to primarily affect immunocompromised patients, but it was later recognized in immunocompetent hosts.23 E muris-like agent was first discovered as a cause of infection in 2009, and cases have been limited to Wisconsin and Minnesota.24,25

Human granulocytic anaplasmosis. A phagocytophilum is transmitted by Ixodes scapularis (the deer tick or blacklegged tick) in the northeastern and upper-midwestern regions of the United States, and I pacificus (the western blacklegged tick) along the northern Pacific coast.1,19,20,26 The 6 states accounting for most cases are New York, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Minnesota, and Wisconsin.27 The white-footed mouse serves as the primary reservoir for A phagocytophilum, and humans are an accidental, “dead-end” host.21 Cases have also been reported to be transmitted via blood transfusion and transplacentally.20,26,28,29

Clinical manifestations of ehrlichiosis

After an incubation time of 5 to 21 days, ehrlichiosis typically presents as a febrile viral-like illness with nonspecific symptoms that include fever, chills, sweats, myalgia, headache, malaise, and cough.1,26,27,31

Gastrointestinal symptoms, arthralgia, photophobia, and nervous system involvement may also occur.1,20,29,32 Gastrointestinal symptoms tend to be more common in HME than HGA.20

Rash occurs in up to one-third of patients with HME, but it is rare in HGA.4,19,20,27 HME presents with more central nervous system involvement (such as meningitis or seizures) than HGA, in which central nervous system involvement is rare.

Severe complications of HME and HGA occur in a minority of cases and may include acute respiratory distress syndrome, renal failure, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, and spontaneous hemorrhage.19 In general, HME is more severe than HGA and is more likely to progress to fulminant toxic or septic shocklike syndrome in rare instances.19

Laboratory tests may reveal leukopenia, lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated liver-associated enzyme levels.1,19,20,26 Anemia and hyponatremia may also be present.4,30

Diagnosis of ehrlichiosis

The most rapid diagnostic method is examination of Wright- or Giemsa-stained peripheral blood smears for morulae, which are cytoplasmic intravacuolar inclusions of bacteria within leukocytes.20 However, its sensitivity is as low as 20% and declines even further after the first week of infection.4,20

PCR testing is the most sensitive and rapid tool available during acute infection.1,20,26,30,31 However, due to waning of the bacteremic phase, its sensitivity decreases after the first week of infection and after treatment is started.19,20

Serologic detection of antibodies with an indirect immunofluorescence assay is the most frequently used test for diagnosis of ehrlichiosis, and paired serology demonstrating seroconversion (at least a 4-fold increase in titer, with a minimal titer of 1:64) is most sensitive (82% to 100%).4,19,20,26 Cross-reactivity can occur, so testing for antibodies to both A phagocytophilum and E chaffeensis might assist in a more accurate diagnosis in areas where tick vectors overlap.4,19,20,26

HGA and HME can be isolated through cell culture in blood or cerebrospinal fluid. However, this is labor-intensive and performed in only a few specialized laboratories.4,19,20,27,31

Treatment of ehrlichiosis

If ehrlichiosis is suspected, treatment should not be delayed; the disease can be life-threatening and the ability to diagnose acute infection is often limited.20,26,32

Doxycycline is the treatment of choice, even in pregnant patients with severe infection and in children.1,19,26,27 Antibiotics are given for 5 to 10 days and continued for at least 3 days after the fever subsides.19,20,26,27,30 In HGA, a 10-day course of doxycycline is recommended to also provide the appropriate length of treatment for Borrelia burgdorferi.1,31

Rifampin is an alternative for those with severe tetracycline allergy, as well as those with mild to moderate infection during pregnancy.1,20,26,29–32

Fever typically resolves within 24 to 48 hours of starting treatment, and persistence of fever over 48 hours after starting antibiotics suggests an alternative diagnosis or possible coinfection.1,4,19,20,26,27,30,32

Persistence of chronic A phagocytophilum or E chaffeensis infection in humans beyond 2 months has not been demonstrated.20,26,30,33 Therefore, antibiotic treatment beyond the acute stage of infection is not indicated.30 Long-term prognosis is favorable, and patients are expected to make a full recovery.26,30