Tickborne diseases other than Lyme in the United States

ABSTRACT

Tickborne diseases are increasing in the United States, and the geographic range of tick vectors is expanding. Tickborne diseases are challenging to diagnose, as they present with vague symptoms such as fever, constitutional symptoms, and nonspecific laboratory abnormalities. A high degree of clinical suspicion is required to make a diagnosis, as patients often do not recall a tick bite. The availability of laboratory testing for tickborne diseases is limited, especially in the acute setting. Therefore, if a tickborne disease is suspected, empiric therapy should often be initiated before laboratory confirmation of the disease is available. This article summarizes the most common non-Lyme tickborne diseases in the United States.

KEY POINTS

- Tickborne illnesses should be considered in patients with known or potential tick exposure presenting with fever or vague constitutional symptoms in tick-endemic regions.

- Given that tick-bite history is commonly unknown, absence of a known tick bite does not exclude the diagnosis of a tick-borne illness.

- Starting empiric treatment is usually warranted before the diagnosis of tickborne illness is confirmed.

- Tick avoidance is the most effective measure for preventing tickborne infections.

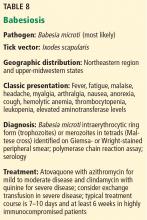

BABESIOSIS

Babesiosis occurs in the northeastern and upper midwestern states, with most cases reported in Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New York, New Jersey, Minnesota, and Wisconsin.31,32,34–36 Outbreaks have also been documented in Washington, California, and Missouri.31,32,35 The spread mimics that of Lyme disease, though it can be slower.34,36–39

Most cases in the Northeast and upper Midwest are caused by Babesia microti, while Babesia duncani has sporadically caused disease along the Pacific coast and Babesia divergens has been found in the Midwest and Northwest.34,36,39

Though babesiosis is usually a tickborne illness, it can also be transmitted through blood transfusion and, rarely, transplacental spread.31,32,34,36,39–41 The I scapularis tick is the host vector for Babesia microti, and transmission of disease requires 24 to 72 hours of attachment to a host.34,35 The primary reservoir for Babesia microti is the white-footed mouse, and humans are accidental hosts.32,34–36,39

Clinical manifestations of babesiosis

Babesia species cause illness by lysing erythrocytes, with resultant cytokine release.34

Symptoms typically appear 1 to 4 weeks after inoculation, after which most cases present as a viral-like illness with gradual onset of fever, chills, sweats, fatigue, malaise, headache, arthralgia, myalgia, nausea, anorexia, and nonproductive cough.32,34–36,39

Physical findings may include splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, jaundice, petechiae, and ecchymosis.32,34–36,39 Rash is seldom present and is not a characteristic feature of babesiosis.35,36

Laboratory features may include thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia, and elevated liver enzyme levels.32,34,36,39

Severe disease can occur in elderly, immunocompromised, or splenectomized individuals and can be life-threatening.34,39 Complications of severe infection can include acute respiratory distress syndrome, diffuse intravascular coagulation, and liver or renal failure.31,32,34–36,39 Splenic infarction or rupture may occur at lower levels of parasitemia in those without other manifestations of severe disease.31 The course can be prolonged and relapsing despite standard antibiotic therapy, typically in the setting of severe immunocompromise.32,34,42,43 Death occurs in up to 10% of severe cases.34

Diagnosis of babesiosis

Babesiosis should be considered if a patient presents with a febrile illness and nonspecific symptoms and comes from an endemic area or has received a blood transfusion within 6 months.34,35

The diagnosis of babesiosis is most commonly made by finding the intraerythrocytic ring form of the organism (trophozoite) on Giemsa- or Wright-stained thin blood smears.34,36,39Babesia can be distinguished from Plasmodia (the agent of malaria) by the rare presence of tetrads of merozoites arranged in a cross-like pattern (the Maltese cross); the absence of hemozoin (brownish deposits) in the ring form; and the occasional presence of extracellular ring forms.34,36

The level of parasitemia (representing the number of parasites per microliter of blood) is generally between 1% and 10%, although it can be as high as 80%.36,39 Because parasitemia is often low early in disease (< 1%), multiple blood smears should be examined.34–36,39

Several real-time PCR assays are available to detect low-grade Babesia microti parasitemia in patients with negative blood smears during early infection.31 These assays have high diagnostic sensitivity and specificity and do not cross-react with other Babesia or Plasmodium species.34–36,39

Paired serology (immunoglobulin G) can confirm infection, although antibody may be absent early in the course of illness.31,34–36,39

Treatment of babesiosis

Current guidelines recommend antimicrobial therapy only for patients with symptoms and positive test results for Babesia.32 Treatment of asymptomatic patients should additionally be considered if parasitemia (not positive PCR or serology) persists for 3 months or longer.32,34–36,39

For mild to moderate babesiosis, the combination of oral atovaquone and azithromycin for 7 to 10 days has similar efficacy and a lower incidence of adverse effects than clindamycin plus quinine.31,32,34,44 For immunocompromised patients, higher doses of azithromycin can be used.31,32

For severe babesiosis or those with risk factors for severe disease, intravenous clindamycin and oral quinine are recommended for 7 to 10 days based on expert opinion.31,32,34–36,39,43 Adverse effects of this regimen include diarrhea, tinnitus, and hearing deficits.35,39 If necessary, intravenous quinidine can be used, but the patient should receive cardiac monitoring for possible prolongation of the QT interval.34,39 As quinine therapy is often interrupted due to the above side effects, alternative regimens such as intravenous azithromycin or clindamycin in combination with oral atovaquone should be considered for severe cases.31 However, these regimens are not well studied.31

Partial or complete exchange transfusion of whole blood or packed red blood cells should be considered in patients with a high level of parasitemia (≥ 10%), severe anemia (hemoglobin < 10 g/dL), or renal, hepatic, or pulmonary compromise.31,32,34–36,39 In critically ill patients, parasitemia should be monitored daily until it has decreased to less than 5%.32,34,39

Generally, symptoms improve within 48 hours of antimicrobial therapy initiation; however, parasitemia may take up to 3 months to resolve.32,34,39 In severely immunocompromised patients, babesiosis may persist or relapse despite appropriate therapy.34,39,42,43 In these cases, at least 6 weeks of antimicrobial therapy is recommended, including 2 weeks of therapy after Babesia organisms are no longer seen on blood smear.31,33,36,39,42

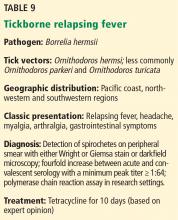

TICKBORNE RELAPSING FEVER

The illness is transmitted by either ticks or body lice. The tick-borne illness is caused by spirochetes of the genus Borrelia and transmitted to humans by the bite of an infected Ornithodoros soft tick.45 Approximately 70% of reported cases in the United States occur in California, Washington, and Colorado.46 Most cases are caused by Borrelia hermsii and are linked to sleeping in rodent-infested cabins in mountainous areas.46 Remarkably, tick-borne borreliae are transmitted within about 30 seconds of tick attachment.47,48

The hallmark of tickborne relapsing fever is febrile episodes lasting 3 to 5 days, with relapses after 5 to 7 days of apparent recovery.49 If untreated, several episodes of fever and nonspecific symptoms will occur before illness resolves spontaneously. Overall mortality rates are very low (< 5%).50

Laboratory confirmation of tickborne relapsing fever is made by detecting spirochetes in a blood smear during a febrile episode or serologic antibody confirmation. However, serologic testing is unhelpful in the acute setting and can yield false-positive results with prior exposure to other Borrelia species (eg, Lyme disease) or other spirochetes. Serologic antibody testing with a 4-fold increase between acute and convalescent samples or PCR can aid in diagnosis, though the latter is available only in research settings.47

The preferred treatment regimen for adults is an oral tetracycline for 10 days. Erythromycin is recommended when tetracyclines are contraindicated.51

When starting treatment, all patients should be monitored closely for the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction (rigors, hypotension, and high fevers), which develops in over 50% of cases as a result of rapid spirochetal killing and massive cytokine release.52