Preventing infection after cesarean delivery: 5 more evidence-based measures to consider

In this article

Preoperative vaginal cleansing

A preoperative antiseptic vaginal scrub is often used as an additional step to help reduce postcesarean infection.

Does cleansing the vagina with povidone-iodine before surgery further reduce the risk of endometritis and wound infection?

Multiple studies have sought to determine if cleansing the vagina with an antiseptic solution further reduces the incidence of postcesarean infection beyond what can be achieved with systemic antibiotic prophylaxis. These studies typically have focused on 3 specific outcomes: endometritis, wound (surgical site) infection, and febrile morbidity. The term febrile morbidity is defined as a temperature ≥100.4°F (38°C) on any 2 postoperative days excluding the first 24 hours. However, many patients who meet the standard definition of febrile morbidity may not have a proven infection and will not require treatment with antibiotics. The more precise measures of outcome are distinctly symptomatic infections, such as endometritis and wound infection, although, as noted in the review of published studies below, some authors continue to use the term febrile morbidity as one measure of postoperative complications.

In a randomized, placebo-controlled trial (RCT) of 308 women having a nonemergent cesarean delivery, Starr and colleagues reported a decreased incidence of postoperative endometritis in women who received a 30-second vaginal scrub with povidone-iodine compared with women who received only an abdominal scrub (7.0% vs 14.5%, P<.05).1 The groups did not differ in the frequency of wound infection (0.7% vs 1.2%, P = .4) or febrile morbidity (23.9% vs 28.3%, P = .4).1

In another RCT, Haas and colleagues found that preoperative vaginal cleansing with povidone-iodine compared with an abdominal scrub alone was associated with a decreased incidence of a composite measure of postoperative morbidity (6.5% vs 11.7%; relative risk [RR], 0.55; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.26–1.11; P = .11).2 The postoperative composite included fever, endometritis, sepsis, readmission, and wound infection.

Subsequently, Asghania and associates conducted a double-blind, nonrandomized study of 568 women having cesarean delivery who received an abdominal scrub plus a 30-second vaginal scrub with povidone-iodine or received an abdominal scrub alone.3 They documented a decreased incidence of postoperative endometritis in the women who received the combined scrub (1.4% vs 2.5%; P = .03, adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 0.03; 95% CI, 0.008–0.7). The authors observed no significant difference in febrile morbidity (4.9% vs 6.0%; P = .73) or wound infection (3.5% vs 3.2%; P = .5).3

Yildirim and colleagues conducted an RCT comparing rates of infection in 334 women who received an abdominal scrub plus vaginal cleansing with povidone-iodine and 336 patients who had only a standard abdominal scrub.4 They documented a decreased incidence of endometritis in women who received the vaginal scrub (6.9% vs 11.6%; P = .04; RR for infection in the control group, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.03–2.76.) The authors found no difference in febrile morbidity (16.5% vs 18.2%; P = .61) or wound infection (1.8% vs 2.7%; P = .60). Of note, in excluding from the analysis women who had ruptured membranes or who were in labor, the investigators found no differences in outcome, indicating that the greatest impact of vaginal cleansing was in the highest risk patients.

In 2014, Haas and associates published a Cochrane review evaluating the effectiveness of preoperative vaginal cleansing with povidone-iodine.5 The authors reviewed 7 studies that analyzed outcomes in 2,635 women. They concluded that vaginal preparation with povidone-iodine at the time of cesarean delivery significantly decreased postoperative endometritis when compared with the control group (4.3% vs 8.3%; RR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.25–0.81). They also noted that the most profound impact of vaginal cleansing was in women who were in labor before delivery (7.4% vs 13.0%; RR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.34–0.95) and in women with ruptured membranes at the time of delivery (4.3% vs 17.9%; RR, 0.24; 95% CI, 0.10–0.55). The authors did not find a significant difference in postoperative wound infection or frequency of fever in women who received the vaginal scrub.

Related article:

STOP using instruments to assist with delivery of the head at cesarean

A notable exception to the beneficial outcomes reported above was the study by Reid et al.6 These authors randomly assigned 247 women having cesarean delivery to an abdominal scrub plus vaginal scrub with povidone-iodine and assigned 251 women to only an abdominal scrub. The authors were unable to document any significant difference between the groups with respect to frequency of fever, endometritis, and wound infection.

Other methods of vaginal preparation also have been studied. For example, Pitt and colleagues conducted a double-blind RCT of 224 women having cesarean delivery and compared preoperative metronidazole vaginal gel with placebo.7 Most of the patients in this trial also received systemic antibiotic prophylaxis after the umbilical cord was clamped. The authors demonstrated a decreased incidence of postcesarean endometritis in women who received the intravaginal antibiotic gel (7% vs 17%; RR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.19–0.92). There was no difference in febrile morbidity (13% vs 19%; P = .28) or wound infection (4% vs 3%, P = .50).

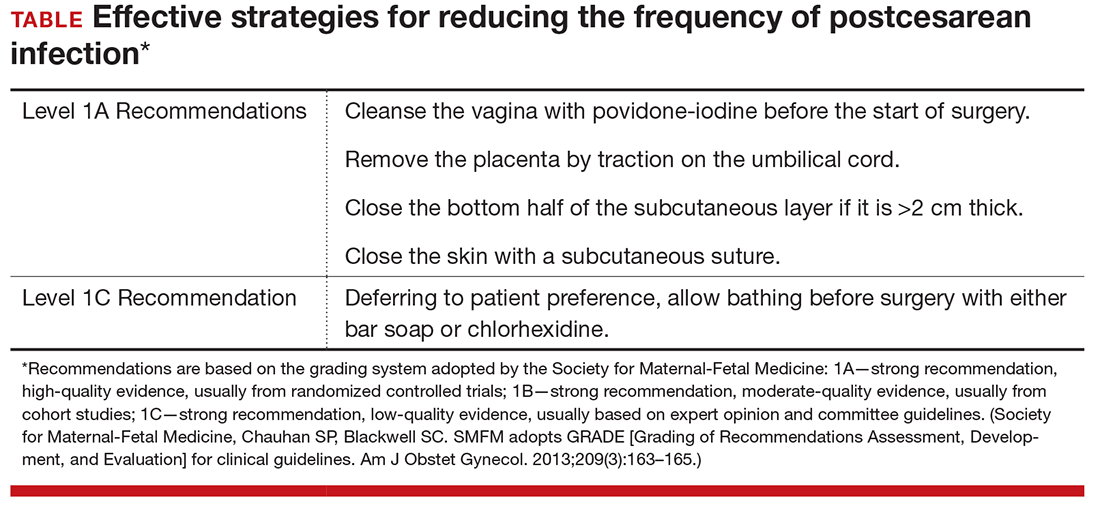

What the evidence says

Consider vaginal preparation with povidone-iodine at the time of cesarean delivery to reduce the risk of postpartum endometritis. Do not expect this intervention to significantly reduce the frequency of wound infection. Vaginal cleansing is of most benefit to women who have ruptured membranes or are in labor at the time of delivery (Level I Evidence, Level A Recommendation; TABLE). Whether vaginal preparation with chlorhexidine with 4% alcohol would have the same beneficial effect has not been studied in a systematic manner.