Hospitalists as Triagists: Description of the Triagist Role across Academic Medical Centers

From the hospitalist perspective, triaging involves the evaluation of a patient for potential admission to an inpatient service. Although traditionally done by residents, many academic hospitalist groups have assumed the responsibility for triaging. We conducted a cross-sectional survey of 235 adult hospitalists at 10 academic medical centers (AMCs) to describe the similarities and differences in the triagist role and assess the activities and skills associated with the role. Eight AMCs have a defined triagist role; at the others, hospitalists supervise residents/advanced practice providers. The triagist role is generally filled by a faculty physician and shared by all hospitalists. We found significant variability in verbal communication practices (P = .02) and electronic communication practices (P < .0001) between the triagist and the current provider (eg, emergency department, clinic provider), and in the percentage of patients evaluated in person (P < .0001). Communication skills, personal efficiency, and systems knowledge are dominant themes of attributes of an effective triagist.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Differences within AMCs

Variability within AMCs was greatest for the rate of verbal communication practices, with a typical interquartile range (IQR) of 20% to 90% among the hospitalists within a given AMC and for the rate of electronic communication with a typical IQR of 0% to 50%. For other survey questions, the IQR was typically 15 to 20 percentage points.

Thematic Analysis

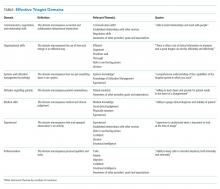

We received 207 and 203 responses (88% and 86%, respectively) to the open-ended questions “What qualities does an effective triagist have?’ and ‘What qualities make a triagist ineffective?” We identified 22 themes for effective and ineffective qualities, which were grouped into seven domains (Table). All themes had at least three mentions by respondents. The three most frequently mentioned themes, communication skills, efficiency, and systems knowledge, had greater than 60 mentions.

DISCUSSION

Our study of the triagist role at 10 AMCs describes critical triagist functions and identifies key findings across and within AMCs. Twenty-eight percent of hospitalists reported admitting patients even when the patient did not meet the admission criteria, consistent with previous research demonstrating the influence of factors other than clinical disease severity on triage decisions.10 However, preventable admissions remain a hospital-level quality metric.11,12 Triagists must often balance each patient’s circumstances with the complexities of the system. Juggling the competing demands of the system while providing patient-centered care can be challenging and may explain why attending physicians are more frequently filling this role.13

Local context/culture is likely to play a role in the variation across sites; however, compensation for the time spent may also be a factor. If triage activities are not reimbursable, this could lead to less documentation and a lower likelihood that patients are evaluated in person.14 This reason may also explain why all hospitalists were required to serve as a triagist at most sites.

Currently, no consensus definition of the triagist role has been developed. Our results demonstrate that this role is heterogeneous and grounded in the local healthcare system practices. We propose the following working definition of the triagist: a physician who assesses patients for admission, actively supporting the transition of the patient from the outpatient to the inpatient setting. A triagist should be equipped with a skill set that includes not only clinical knowledge but also emphasizes systems knowledge, awareness of others’ goals, efficiency, an ability to communicate effectively, and the knowledge of UM. We recommend that medical directors of hospitalist programs focus their attention on locally specific, systems-based skills development when orienting new hospitalists. The financial aspects of cost should be considered and delineated as well.

Our analysis is limited in several respects. Participant AMCs were not randomly chosen, but do represent a broad array of facility types, group size, and geographic regions. The low response rates at some AMCs may result in an inaccurate representation of those sites. Data was not obtained on hospitalists that did not respond to the survey; therefore, nonresponse bias may affect outcomes. This research used self-report rather than direct observation, which could be subject to recall and social desirability bias. Finally, our results may not be generalizable to nonacademic institutions.