Hospitalists as Triagists: Description of the Triagist Role across Academic Medical Centers

From the hospitalist perspective, triaging involves the evaluation of a patient for potential admission to an inpatient service. Although traditionally done by residents, many academic hospitalist groups have assumed the responsibility for triaging. We conducted a cross-sectional survey of 235 adult hospitalists at 10 academic medical centers (AMCs) to describe the similarities and differences in the triagist role and assess the activities and skills associated with the role. Eight AMCs have a defined triagist role; at the others, hospitalists supervise residents/advanced practice providers. The triagist role is generally filled by a faculty physician and shared by all hospitalists. We found significant variability in verbal communication practices (P = .02) and electronic communication practices (P < .0001) between the triagist and the current provider (eg, emergency department, clinic provider), and in the percentage of patients evaluated in person (P < .0001). Communication skills, personal efficiency, and systems knowledge are dominant themes of attributes of an effective triagist.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Qualitative

Responses to open-ended questions were analyzed using thematic analysis.9 Three independent reviewers (STV, JC, ESW) read, analyzed, and grouped the responses by codes. Codes were then assessed for overlap and grouped into themes by one reviewer (STV). A table of themes with supporting quotes and the number of mentions was subsequently developed by all three reviewers. Similar themes were combined to create domains. The domains were reviewed by the steering committee members to create a consensus description (Appendix 3).

The University of Texas Health San Antonio’s Institutional Review Board and participating institutions approved the study as exempt.

RESULTS

Site Characteristics

Representatives from 10 AMCs reported data on a range of one to four hospitals for a total of 22 hospitals. The median reported that the number of medical patients admitted in a 24-hour period was 31-40 (range, 11-20 to >50). The median group size of hospitalists was 41-50 (range, 0-10 to >70).

The survey response rate was 40% (n = 235), ranging from 9%-70% between institutions. Self-identified female hospitalists accounted for 52% of respondents. Four percent were 25-29 years old, 66% were 30-39 years old, 24% were 40-49 years old, and 6% were ≥50 years old. The average clinical time spent as a triagist was 16%.

Description of Triagist Activities

The activities identified by the majority of respondents across all sites included transferring patients within the hospital (73%), and assessing/approving patient transfers from outside hospitals and clinics (82%). Internal transfer activities reported by >50% of respondents included allocating patients within the hospital or bed capacity coordination, assessing intensive care unit transfers, assigning ED admissions, and consulting other services. The ED accounted for an average of 55% of calls received. Respondents also reported being involved with the documentation related to these activities.

Similarities and Differences across AMCs

Two AMCs did not have a dedicated triagist; instead, physicians supervised residents and advanced practice providers. Among the eight sites with triagists, triaging was predominantly done by faculty physicians contacted via pagers. At seven of these sites, 100% of hospitalists worked as triagists. The triage service was covered by faculty physicians from 8-24 hours per day.

Bed boards and transfer centers staffed by registered nurses, nurse coordinators, house supervisors, or physicians were common support systems, though this infrastructure was organized differently across institutions. A UM review before admission was performed at three institutions 24 hours/day. The remaining institutions reviewed patients retrospectively.

Twenty-eight percent of hospitalists across all sites “Disagreed” or “Strongly disagreed” that a patient must meet UM criteria for admission. Forty-two percent had “Frequent” different opinions regarding patient management than the consulting provider.

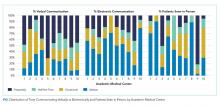

Triagist and current provider communication practices varied widely across AMCs (Figure). There was significant variability in verbal communication (P = .02), with >70% of respondents at two AMCs reporting verbal communication at least half the time, but <30% reporting this frequency at two other AMCs. Respondents reported variable use of electronic communication (ie, notes/orders in the electronic health record) across AMCs (

The practice of evaluating patients in person also varied significantly across AMCs (P < .0001, Figure). Across hospitalists, only 28% see patients in person about “Half-the-Time” or more.