Barriers to Providing VTE Chemoprophylaxis to Hospitalized Patients: A Nursing-Focused Qualitative Evaluation

BACKGROUND: Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a serious medical condition that results in preventable morbidity and mortality.

OBJECTIVES: The objective of this study was to identify nursing-related barriers to administration of VTE chemoprophylaxis to hospitalized patients.

DESIGN: This was a qualitative study including nurses from five inpatient units at one hospital.

METHODS: Observations were conducted on five units to gain insight into the process for administering chemoprophylaxis. Focus group interviews were conducted with nurses and were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed using the Theoretical Domains Framework to identify barriers to providing VTE chemoprophylaxis.

RESULTS: We conducted 14 focus group interviews with nurses from five inpatient units to assess nurses’ perceptions of barriers to administration of VTE chemoprophylaxis. The barriers identified included nurses’ misconceptions that ambulating patients did not require chemoprophylaxis, nurses’ uncertainty when counseling patients on the importance of chemoprophylaxis, and a lack of comparative data for nurses regarding their specific refusal rates.

CONCLUSIONS: Multiple factors act as barriers to patients receiving VTE chemoprophylaxis. These barriers are often modifiable targets for quality improvement. There is a need to focus on behavior changes that will remove or minimize barriers and equip nurses to ensure administration of VTE chemoprophylaxis by engaging patients in their care.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

METHODS

Inpatient Unit Selection

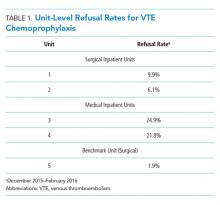

The study team accessed data from the hospital’s Enterprise Data Warehouse to review patient refusal rates of VTE chemoprophylaxis for each inpatient unit in the hospital. Patient refusal was utilized as a proxy measure for the behavior of nurses attempting to administer VTE chemoprophylaxis. Of the 14 medical and surgical units in the hospital, two medical and two surgical units were selected to participate in the qualitative evaluation based on having the highest patient refusal rates. One unit (surgical) was also selected to serve as a benchmark because it had the lowest patient refusal rate. Table 1 includes the refusal rates for the five units. Given the low refusal rate for the best performing unit, we suspected that it would be possible to decrease the patient refusal rate for other units with similar patient populations and interprofessional teams at the institution.

Observations

We observed chemoprophylaxis administration on the five units to understand the process for ordering and administering chemoprophylaxis. An observation protocol was utilized to document the date, time, and location of the observation as well as descriptive notes including accounts of particular events.19,20 Observations occurred in May 2016 and informed the creation of a process map outlining the procedure for ordering and administering VTE chemoprophylaxis. The process map was utilized to create the focus group interview guide and ensure the interview guide included pertinent questions for each step of the process (Appendix A).

Focus Group Interviews

We conducted focus group interviews with day and night shift nurses on the five units to assess nurses’ understanding of VTE chemoprophylaxis and nurses’ perceptions of barriers to administration of VTE chemoprophylaxis. The study team chose to conduct focus group interviews in an effort to maximize participation and to speak with multiple nurses within a shorter period of time. The focus group structure allowed the study team to speak with nurses during their shifts, as one could briefly step out, if required, for patient care and return to rejoin the discussion.

We developed a semistructured interview guide21 with questions focused on identifying nurses’ perceptions of guideline-recommended care for VTE chemoprophylaxis, where they learned these guidelines, how nurses discuss chemoprophylaxis with patients, how they handle the conversation with patients who refuse, and if there are times when chemoprophylaxis is not necessary. The interview guide was vetted by a multidisciplinary team consisting of clinical nursing coordinators and nurse managers from medical and surgical units, hospital quality leaders, surgeons and general internists, and qualitative research experts. The interview guide is included as Appendix B.

The unit clinical coordinators and nurse managers identified dates and times for the focus groups that would be minimally disruptive to the unit. For each of the four units with a high patient refusal rate, two focus groups were conducted during the lunch hour and one was conducted at the end of the night shift to ensure that both day and night shift nurses were included in the study. Two focus groups were conducted with the best-practice unit during the lunch hour. For each focus group, the clinical coordinator identified two to eight nurses who could step away from patient care to participate or who had completed their shifts. In total, approximately 67 nurses participated in the focus groups.

The focus groups (n = 14) lasted approximately 40 minutes during May and June 2016. Two members of the study team cofacilitated interviews, which were recorded and transcribed verbatim.