Nurse Responses to Physiologic Monitor Alarms on a General Pediatric Unit

BACKGROUND: Hospitalized children generate up to 152 alarms per patient per day outside of the intensive care unit. In that setting, as few as 1% of alarms are clinically important. How nurses make decisions about responding to alarms, given an alarm’s low specificity for detecting clinical deterioration, remains unclear.

OBJECTIVE: Our objective was to describe how bedside nurses think about and act upon monitor alarms for hospitalized children. This was a qualitative study that involved the direct observation of nurses working on a general pediatric unit at a large children’s hospital.

MEASUREMENTS: We used a structured tool that included predetermined categories to assess nurse responses to monitor alarms. Data on alarm frequency and type were pulled from bedside monitors.

RESULTS: We conducted 61.3 patient-hours of observation with nine nurses, in which we documented 207 nurse responses to patient alarms. For 67% of alarms heard outside of the room, the nurse decided not to respond without further assessment. Nurses most commonly cited reassuring clinical context (eg, medical team in room), as the rationale for alarm nonresponse. The nurse deemed clinical intervention necessary in only 14 (7%) of the observed responses.

CONCLUSION: Nurses rely on clinical and contextual details to determine how to respond to alarms. Few of the alarm responses in our study resulted in a clinical intervention. These findings suggest that multiple system-level and educational interventions may be necessary to improve the efficacy and safety of continuous monitoring.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to assess the percentage of each nurse response category and each alarm type (eg, heart rate and respiratory rate). The observed alarm rate was calculated by taking the total number of observed alarms (ie, alarms noted by the nurse) divided by the total number of patient-hours observed. The monitor-generated alarm rate was calculated by taking the total number of alarms from the bedside-alarm generated data divided by the number of patient-hours observed.

Electronically recorded observations using the work-sampling program were cross-referenced with hand-written field notes to assess for any discrepancies or identify relevant events not captured by the program. Three study team members (AML, KMT, and ACS) reviewed each observation independently and compared field notes to ensure accurate categorization. Discrepancies were referred to the larger study group in cases of uncertainty.

RESULTS

Nine nurses had monitored patients during the available observations and participated in 19 observation sessions, which included 35 monitored patients for a total of 61.3 patient-hours of observation. Nurses were observed for a median of two times each (range 1-4). The median number of monitored patients during a single observation session was two (range 1-3). Observed nurses were female with a median of eight years of experience (range 0.5-26 years). Patients represented a broad range of age categories and were hospitalized with a variety of diagnoses (Table). Nurses, when queried at the start of the observation, felt that monitors were necessary for 29 (82.9%) of the observed patients given either patient condition or unit policy.

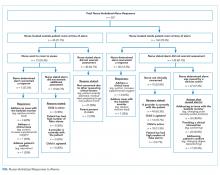

A total of 207 observed nurse responses to alarms occurred during the study period for a rate of 3.4 responses per patient per hour. Of the total number of responses, 45 (21.7%) were noted outside of a patient room, and in 15 (33.3%) the nurse chose to go to the room. The other 162 were recorded when the nurse was present in the room when the alarm activated. Of the 177 in-person nurse responses, 50 were related to a pulse oximetry alarm, 66 were related to a heart rate alarm, and 61 were related to a respiratory rate alarm. The most common observed in-person response to an alarm involved the nurse judging that no intervention was necessary (n = 152, 73.1%). Only 14 (7% of total responses) observed in-person responses involved a clinical intervention, such as suctioning or titrating supplemental oxygen. Findings are summarized in the Figure and describe nurse-verbalized reasons to further assess (or not) and then whether the nurse chose to take action (or not) after an alarm.

Alarm data were available for 17 of the 19 observation periods during the study. Technical issues with the central alarm collection software precluded alarm data collection for two of the observation sessions. A total of 483 alarms were recorded on bedside monitors during those 17 observation periods or 8.8 alarms per patient per hour, which was equivalent to 211.2 alarms per patient-day. A total of 175 observed responses were collected during these 17 observation periods. This number of responses was 36% of the number we would have expected on the basis of the alarm count from the central alarm software.

There were no patients transferred to the intensive care unit during the observation period. Nurses who chose not to respond to alarms outside the room most often cited the brevity of the alarm or other reassuring contextual details, such as that a family member was in the room to notify them if anything was truly wrong, that another member of the medical team was with the patient, or that they had recently assessed the patient and thought likely the alarm did not require any action. During three observations, the observed nurse cited the presence of family in the patient’s room in their decision not to conduct further assessment in response to the alarm, noting that the parent would be able to notify the nurse if something required attention. On two occasions in which a nurse had multiple monitored patients, the observed nurse noted that if the other monitored patients were alarming and she happened to be in another patient’s room, she would not be able to hear them. Four nurses cited policy as the reason a patient was on monitors (eg, patient was on respiratory support at night for obstructive sleep apnea).