Past is Prologue

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

A CMV antigenemia assay returned positive, suggesting prior CMV infection. However, to diagnose CMV pneumonia, the virus must be detected in BAL fluid by PCR or cytologic analysis. CMV infection has been associated with cytopenias, HLH, pancreatic infiltration, and an increased risk for fungal infections and EBV-related PTLD. CMV infection could explain the first phase of this patient’s illness. Serum and BAL PCR for CMV are advised. Meanwhile, EBV testing indicates prior infection but does not distinguish between recent or more distant infection. EBV has been implicated in the pathophysiology of PTLD, as EBV-infected lymphoid tissue may proliferate in a variety of organs under reduced T-cell surveillance. EBV infection or PTLD with resulting immunomodulation may pose other explanations for this patient’s development of PCP infection. Cytologic analysis of the BAL fluid and marrow aspirate for evidence of PTLD is warranted. Finally, CMV, EBV, and PTLD have each been reported to trigger HLH. Though this patient has fevers, mild marrow hemophagocytosis, elevated serum ferritin, and elevated serum IL-2 receptor levels, he does not meet other diagnostic criteria for HLH (such as more pronounced cytopenias, splenomegaly, hypertriglyceridemia, hypofibrinogenemia, and low or absent natural killer T-cell activity). However, HLH may be muted in this patient because he was prescribed cyclosporine, which has been used in HLH treatment protocols.

On the 11th hospital day, the patient developed hemorrhagic shock due to massive hematemesis and was transferred to the intensive care unit. His hemoglobin level was 5.9 g/dL. A total of 18 units of packed red blood cells were transfused over the following week for ongoing gastrointestinal bleeding. The serum LDH level increased to 4,139 IU/L, and the ferritin level rose to 7,855 ng/mL. The EBV copy level by serum PCR returned at 1 × 106 copies/mL (normal range, less than 2 x 102 copies/mL). The patient was started on methylprednisolone (1 g/day for three days) and transitioned to dexamethasone and cyclosporine for possible EBV-related HLH. Ceftazidime, vancomycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and ciprofloxacin were administered. Amphotericin-B was initiated empirically for potential fungal pneumonia. Ganciclovir was continued. However, the patient remained in shock despite vasopressors and transfusions and died on the 22nd hospital day.

The patient deteriorated despite broad antimicrobial therapy. Laboratory studies revealed EBV viremia and rising serum LDH. Recent EBV infection may have induced PTLD in the gastrointestinal tract, which is a commonly involved site among affected renal transplant patients. Corticosteroids and stress from critical illness can contribute to intestinal mucosal erosion and bleeding from a luminal PTLD lesion. Overall, the patient’s condition was likely explained by EBV infection, which triggered HLH and gastrointestinal PTLD. The resulting immunomodulation increased his risk for PCP infection beyond that conferred by chronic immunosuppression. It is still possible that he had concomitant CMV pneumonia, Aspergillus pneumonia, or even pulmonary PTLD, in addition to the proven PCP diagnosis.

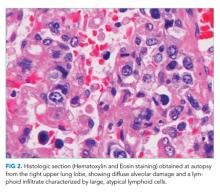

An autopsy was performed. Atypical lymphocytic infiltration and diffuse alveolar damage were shown in the right upper lobe (Figure 2). EBV RNA-positive atypical lymphocytes coexpressing CD20 were demonstrated in multiple organs including the bone marrow, lungs, heart, stomach, adrenal glands, duodenum, ileum, and mesentery (Figure 3). This confirmed the diagnosis of an underlying EBV-positive posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder. Serum and BAL CMV PCR assays returned negative. Neither CMV nor Aspergillus was identified in autopsy specimens.