Past is Prologue

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Infectious pneumonia is the principal concern. A diagnosis of PCP could be unifying, given dyspnea, progressive respiratory failure with hypoxia, and elevated LDH in an immunocompromised patient who is not prescribed PCP prophylaxis. The bilateral lung infiltrates and the absence of thoracic adenopathy or pleural effusions are characteristic of PCP as well. However, caution should be exercised in making specific infectious diagnoses in immunocompromised hosts on the basis of clinical and imaging findings alone. There can be overlap in the radiologic appearance of various infections (eg, CMV pneumonia can also present with bilateral ground-glass infiltrates, with concurrent fever, hypoxia, and pancytopenia). Additionally, more than one pneumonic pathogen may be implicated (eg, acute viral pneumonia superimposed on indolent fungal pneumonia). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of respiratory secretions for viruses, serum PCR and serologic testing for herpes viruses, and serum beta-D-glucan and galactomannan assays are indicated. Serum serologic testing for fungi and bacteria such as Nocardia can be helpful, though the negative predictive values of these tests may be reduced in patients with impaired humoral immunity. Timely bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) with microbiologic and PCR analysis and cytology is advised.

Fever, elevated LDH, cytopenias, and pulmonary infiltrates also raise suspicion for an underlying hematologic malignancy, such as PTLD. However, pulmonary PTLD is seen more often in lung transplant recipients than in patients who have undergone transplantation of other solid organs. In kidney transplant recipients, PTLD most commonly manifests in the allograft itself, gastrointestinal tract, central nervous system, or lymph nodes; lung involvement is less common. Chest imaging in affected patients may reveal nodular or reticulonodular infiltrates of basilar predominance, solitary or multiple masses, cavitating or necrotic lesions, and/or lymphadenopathy. In this patient who has undergone renal transplantation, late-onset PTLD with isolated pulmonary involvement, with only ground-glass opacities on lung imaging, would be an atypical presentation of an uncommon syndrome.

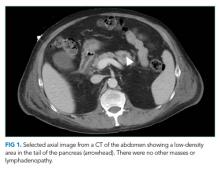

Despite empiric treatment with antibiotics and antiviral agents, the patient’s fever persisted. His respiratory rate increased to 30 breaths per minute. His hypoxia worsened, and he required nasal cannula high-flow oxygen supplementation at 30 L/min with a fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) of 40%. On the fifth hospital day, contrast CT scan of the chest and abdomen showed new infiltrates in the bilateral upper lung fields as well as an area of low density in the tail of the pancreas without a focal mass (Figure 1). At this point, BAL was performed, and fluid PCR analysis returned positive for Pneumocystis jirovecii. CMV direct immunoperoxidase staining of leukocytes with peroxidase-labeled monoclonal antibody (C7-HRP test) was positive at five cells per 7.35 × 104 peripheral blood leukocytes. The serum Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) viral capsid antigen (VCA) IgG was positive, while VCA IgM and EBV nuclear antigen IgG were negative. A bone marrow biopsy revealed mild hemophagocytosis. His serum soluble interleukin-2 (sIL2R) level was elevated at 5,254 U/mL (normal range, 122-496 U/mL). Given the BAL Pneumocystis PCR result, the dose of prednisolone was increased to 30 mg/day, and the patient’s fever subsided. Supplemental oxygen was weaned to an FiO2 of 35%.

These studies should be interpreted carefully considering the biphasic clinical course. After two months of exertional dyspnea, the patient acutely developed persistent fever and progressive lung infiltrates. His clinical course, the positive PCR assay for Pneumocystis jirovecii in BAL fluid, and the compatible lung imaging findings make Pneumocystis jirovecii a likely pathogen. But PCP may only explain the second phase of this patient’s illness, considering its often-fulminant course in HIV-negative patients. To explain the two months of exertional dyspnea, marrow hemophagocytosis, pancreatic abnormality, and perhaps even the patient’s heightened susceptibility to PCP infection, an index of suspicion should be maintained for a separate, antecedent process. This could be either an indolent infection (eg, CMV or Aspergillus pneumonia) or a malignancy (eg, lymphoma or PTLD). Completion of serum serologic testing for viruses, bacteria, and fungi and comprehensive BAL fluid analysis (culture, viral PCR, and cytology) is recommended.