Pharmacologic Management of Malignant Bowel Obstruction: When Surgery Is Not an Option

Malignant bowel obstruction (MBO) complicates 3%-15% of cancers and often necessitates inpatient admission. Hospitalists are increasingly involved in treating patients with MBO and coordinating their care across multiple subspecialties. Direct resolution of the obstruction via surgical or interventional means is always preferable. When such options are not possible, pharmacological treatments are the mainstay of therapy. Medications such as somatostatin analogs, steroids, H2-blockers, and other modalities can be effective in palliation and possible resolution of obstruction. Awareness of these pharmacologic therapies can aid hospitalists in treating patients who are confronted with this devastating condition.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Analgesics

Pain control is an essential part of the palliative treatment of MBO as bowel distention, secretions, and edema can cause rapid onset of pain. Parenteral step three opioids remain the optimal initial choice since patients are unable to take medications orally and may have compromised absorption. Opioids address both the colicky and continuous aspects of MBO pain.

Short-acting intravenous opioids such as morphine or hydromorphone may be scheduled every four hours with breakthrough dosing every hour in between. Alternatively, analgesics can be administered via a patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pump.1 Although doses vary across patients, opioid-naïve patients can be initiated on a low dose therapy such as hydromorphone 0.2 mg IV/SC or morphine 1 mg IV/SC every four hours as needed for pain control.

Ongoing pain management for patients with MBO requires coordination of care. Many patients will elect to receive hospice care following discharge. Direct communication with palliative consultants and hospice providers can help facilitate a smooth transition. In patients for whom bowel obstruction resolves, transition to oral opioids based on morphine equivalent daily dose is indicated with further dose adjustment as patients may have reduced pain at this stage.

Options for patients with unresolved obstruction include transdermal and sublingual preparations as well as outpatient PCA with hospice support. Transdermal fentanyl patch can be useful but onset of peak levels occur within 8-12 hours.20 The patch is usually exchanged every 72 hours and is most effective when applied to areas containing adipose tissue which may limit its use in cachectic patients. The liquid preparation of methadone can be useful even in patients with unresolved MBO. Its lipophilic properties allow for ease of absorption.21 A baseline electrocardiogram (EKG) is recommended prior to methadone initiation due to the potential for QT prolongation. Methadone should not be a first-line option for opioid-naïve individuals due to its longer onset of action which limits rapid dose titration. Close collaboration with palliative medicine is highly recommended when using longer acting opioids.

Antisecretory Agents

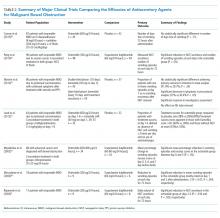

Antisecretory agents are a mainstay of the pharmacologic management of inoperable MBO. Medications that reduce secretions and bowel edema include: somatostatin analogs, H2-blockers, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), steroids, and anticholinergic agents. Table 2 summarizes the major studies comparing various antisecretory medications.

Octreotide, a somatostatin analog, has been increasingly used for the palliative treatment of MBO. The mechanism of action involves splanchnic vasoconstriction, reduction of intestinal and pancreatic secretions (via inhibition of VIP), decrease in gastric emptying, and slowing of smooth muscle contractions.22 Octreotide comes in an immediate-release formulation with an initial subcutaneous dose of 100 µg three or four times per day. Most patients will require 300-800 µg/day, maximum dose being up to 1 mg/day.22,23 A long-acting formulation, lanreotide, exists but can be difficult to obtain and may not provide the immediate relief needed in an acute care setting.

Initiation of octreotide should be considered in the presence of persistent symptoms. Studies have suggested that the benefit of octreotide is most apparent in the first three days of treatment (range 1-5 days).6,22,24 The medication should be discontinued if there is no clinical improvement such as reduction of NG tube output. Octreotide has been shown to be more efficacious than anticholinergic agents in reducing secretions as well as frequency of nausea and vomiting.8,25-28 Octreotide expedites NG tube removal, recovery of bowel function, and improvement in quality of life.29-32 The medication should also be considered in cases of recurrent MBO that previously responded to the medication.

Octreotide is considered the first-line agent in the palliative treatment of MBO, however the medication is costly. Recent studies suggest combination therapy with steroids and H2-blockers or PPIs may be an equally effective and less expensive alternative. The primary rationale for the use of steroids in MBO is their ability to decrease peritumoral edema and promote salt and water absorption from the intestine.1,2 PPIs and H2-blockers decrease distension, pain, and vomiting by reducing the volume of gastric secretions.33 A recent meta-analysis of phase 3 trials found both PPIs and H2-blockers to be effective in lowering volumes of gastric aspirates with ranitidine being slightly superior.34

Initial research into the utility of steroids in MBO garnered mixed results. One study showed marginal benefit for steroid plus octreotide combination therapy compared to octreotide, in a cohort of 27 patients.35 A subsequent review of practice patterns in the management of terminal MBO in Japan found that patients given steroids in combination with octreotide compared to octreotide alone were more likely to undergo early NG tube removal.36 A 1999 systematic review of corticosteroid treatment of MBO concluded low morbidity associated with the medications with a trend toward benefit that was not statistically significant.37 A 2015 study by Currow showed the addition of octreotide in patients already on a regime of dexamethasone and ranitidine did not improve the number of days free from vomiting but did reduce vomiting episodes in those with the most refractory symptoms.38

Collectively, the studies suggest that combination therapy with steroid and PPI or H2 blocker could be a less expensive option in the initial management of MBO. Alternatively, steroids may provide additional relief in patients with continued symptoms on octreotide and H2-blockers. Dexamethasone is preferable given its longer half-life and decreased propensity for sodium retention. Dosing of dexamethasone should be 8 mg IV once a day.38

Anticholinergic agents also reduce secretions. However, they are considered second-line therapy given their lower efficacy compared to other treatment options as well as their propensity to worsen cognitive function.1,2 Anticholinergics may benefit patients with continued symptoms who cannot tolerate the side effects of other treatments. Scopolamine, also known as hyoscine hydrobromide in the US, should be avoided as it crosses the blood-brain barrier. The quaternary formulation, scopolamine butylbromide (hyoscine butylbromide), does not pass this barrier but is currently not available in the US. Glycopyrrolate may be considered as it is also a quaternary ammonium compound that does not cross the blood-brain barrier. Several case reports have described its effectiveness in the resolution of refractory nausea and vomiting in combination with haloperidol and hydromorphone for symptom control.39 Effective oral care is imperative if anticholinergics are used in order to prevent the unpleasant feeling of dry mouth.