Pharmacologic Management of Malignant Bowel Obstruction: When Surgery Is Not an Option

Malignant bowel obstruction (MBO) complicates 3%-15% of cancers and often necessitates inpatient admission. Hospitalists are increasingly involved in treating patients with MBO and coordinating their care across multiple subspecialties. Direct resolution of the obstruction via surgical or interventional means is always preferable. When such options are not possible, pharmacological treatments are the mainstay of therapy. Medications such as somatostatin analogs, steroids, H2-blockers, and other modalities can be effective in palliation and possible resolution of obstruction. Awareness of these pharmacologic therapies can aid hospitalists in treating patients who are confronted with this devastating condition.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

INITIAL MANAGEMENT

Fluid resuscitation, electrolyte repletion, and a trial of NG tube decompression are part of the initial management of MBO (Figure ). While studies have shown that moderate intravenous hydration can minimize nausea and drowsiness, excessive fluids may worsen bowel edema and exacerbate vomiting.1,8 NG tube decompression is most effective in patients with proximal obstructions but some studies suggest it can decrease vomiting in patients with colonic obstructions as well.9 Computed tomography imaging can identify the extent of the tumor, the transition point of the obstruction, and any distant metastases. Surgery, Gastroenterology, and/or Interventional Radiology consultation should be obtained early to evaluate options for direct decompression. Hematology/Oncology and Radiation/Oncology referral may help delineate prognosis and achievable outcomes. Emergent exploratory surgery may be required in cases of bowel perforation or ischemia. Otherwise, a planned surgical resection should be considered in those with an isolated resectable lesion and acceptable perioperative risk. Colorectal or duodenal stents may be an option for those who are not surgical candidates or as a bridge to surgery.

As bowel obstruction is often a late manifestation of advanced malignancy, many patients may not be appropriate candidates for operative/interventional treatment due to malnutrition, comorbid conditions, or anatomic considerations. For these individuals, pharmacologic management is the mainstay of treatment. Additionally, the pharmacologic approaches detailed below may provide benefit as adjunctive therapy for patients undergoing procedural intervention.7 Consultation for early palliative care can improve symptom control as well as clarify goals of care.

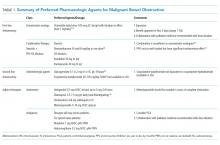

PHARMACOLOGIC MANAGEMENT

Given the pathophysiology of MBO, pharmacologic therapies are focused on controlling nausea and pain while reducing bowel edema and secretions.

Antiemetic Agents

Nausea and vomiting in MBO are due to activation of vagal nerve fibers in the gastric wall and stimulation of the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ).10 Dopamine antagonists have started to gain favor for MBO compared to more commonly used antiemetics such as the serotonin antagonists. Haloperidol should be considered as a first-line antiemetic in patients with MBO. Its potent D2-receptor antagonistic properties block receptors in the CTZ. The high affinity of the drug for only the D2-receptor makes it preferable to alternative agents in the same class such as chlorpromazine. However, haloperidol may cause or worsen QT prolongation and should be avoided in patients with Parkinson’s disease. The medication has less sedative and unwanted anticholinergic side effects due to its limited interaction with histaminergic and acetylcholine receptors.11 Haloperidol has been shown in the past to be efficacious for post-operative nausea but there are few randomized controlled trials in the terminally ill.12 Nonetheless, recent consensus guidelines from the Multinational Association of Supportive Care recommended haloperidol as the initial treatment of nausea for individuals with MBO based on available systematic reviews.10

Other dopamine antagonists remain good options, though they may cause additional side effects due to actions on other receptor types. Metoclopramide, another D2-receptor antagonist, has been shown to be effective in the treatment of nausea and vomiting due to advanced cancer.13 However as a prokinetic agent, this medication should be avoided in those with complete MBO and only considered in those with partial MBO.10,14

Olanzapine, an atypical antipsychotic, may also have a role in controlling nausea in patients with MBO. It functions as a 5-HT2A and D2-receptor antagonist, with a slightly greater affinity for the 5-HT2A receptor. Olanzapine thus can target two critical receptors playing a role in nausea and vomiting. A study of patients with incomplete bowel obstruction found the addition of olanzapine significantly decreased nausea and vomiting in patients who were refractory to other treatments including steroids and haloperidol.15 Olanzapine has the added advantage of single-day dosing as well as an oral disintegrating formulation.16

Intravenous and sublingual preparations of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists such as ondansetron are commonly used in the inpatient setting. These medications are potent antiemetics that exhibit their effects via pathways where serotonin acts as a neurotransmitter.17 An alternative agent, tropisetron, has shown promise when used alone or in conjunction with metoclopramide but is not currently available in the US.18 Granisetron is available in a transdermal formulation, which can be very convenient for patients with bowel obstruction. Its mechanism of action differs from ondansetron as it is an allosteric inhibitor rather than a competitive inhibitor.19 Granisetron needs more specific study with regards to its role in MBO.

Although haloperidol remains the initial choice, combination therapy can help to decrease the risk of extrapyramidal symptoms seen with higher doses of dopaminergic monotherapy.