Home Smoke Exposure and Health-Related Quality of Life in Children with Acute Respiratory Illness

OBJECTIVE: This study aims to assess whether secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure has an impact on health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in children with acute respiratory illness (ARI).

METHODS: This study was nested within a multicenter, prospective cohort study of children (two weeks to 16 years) with ARI (emergency department visits for croup and hospitalizations for croup, asthma, bronchiolitis, and pneumonia) between July 1, 2014 and June 30, 2016. Subjects were surveyed upon enrollment for sociodemographics, healthcare utilization, home SHS exposure (0 or ≥1 smoker in the home), and child HRQOL (Pediatric Quality of Life Physical Functioning Scale) for both baseline health (preceding illness) and acute illness (on admission). Data on insurance status and medical complexity were collected from the Pediatric Hospital Information System database. Multivariable linear mixed regression models examined associations between SHS exposure and HRQOL.

RESULTS: Home SHS exposure was reported in 728 (32%) of the 2,309 included children. Compared with nonexposed children, SHS-exposed children had significantly lower HRQOL scores for baseline health (mean difference –3.04 [95% CI –4.34, –1.74]) and acute illness (–2.16 [–4.22, –0.10]). Associations were strongest among children living with two or more smokers. HRQOL scores were lower among SHS-exposed children for all four conditions but only significant at baseline for bronchiolitis (–2.94 [–5.0, –0.89]) and pneumonia (–4.13 [–6.82, –1.44]) and on admission for croup (–5.71 [–10.67, –0.75]).

CONCLUSIONS: Our study demonstrates an association between regular SHS exposure and decreased HRQOL with a dose-dependent response for children with ARI, providing further evidence of the negative impact of SHS. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2019;14:212-217. © 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

The overall mean HRQOL score at the time of admission was 56 (23), with a range across diagnoses of 49 to 61, with lower scores noted among SHS-exposed children compared with non-SHS-exposed children (adjusted mean difference –2.16 [–4.22, –0.10]). Similar to scores representing baseline health, admission scores were lower across all four conditions for SHS-exposed children. Only children with croup, however, had significantly lower admission scores that also met the MCID threshold (adjusted mean difference –5.71 [–10.67, –0.75]; Table 2).

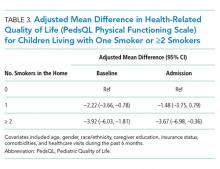

To assess for potential dose-response effects of SHS exposure on HRQOL, we stratified SHS-exposed children into those with one smoker in the home (n = 513) and those with ≥2 smokers in the home (n = 215). Compared with non-SHS-exposed children, both HRQOL scores (baseline health and admission) were lower for SHS-exposed children. Consistent with a dose-response association, scores were lowest for children with ≥2 smokers in the home, both at baseline health (adjusted mean difference –3.92 [–6.03, –1.81]) and on admission (adjusted mean difference –3.67 [–6.98, –0.36]; Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Within a multicenter cohort of 2,309 children hospitalized with ARI, we noted significantly lower HRQOL scores among children exposed to SHS in the home as compared with nonexposed children. Differences were greatest for children living with ≥2 smokers in the home. In analyses stratified by diagnosis, differences in baseline health HRQOL scores were greatest for children with bronchiolitis and pneumonia. Differences in acute illness scores were greatest for children with croup.16

Our study provides evidence for acute and chronic impacts of SHS on HRQOL in children hospitalized with ARI. Although several studies have linked SHS exposure to reduced HRQOL in adults,19,20 few similar studies have been conducted in children. Nonetheless, a wealth of studies have documented the negative impact of SHS exposure on clinical outcomes among children with ARI.8,10,21-23 Our findings that home SHS exposure was associated with reduced HRQOL among our cohort of children with ARI are therefore consistent with related findings in adults and children. The observation that the effects of SHS exposure on HRQOL were greatest among children living with ≥2 smokers provides further evidence of a potential causal link between regular SHS exposure and HRQOL.

Although the magnitude and significance of associations between SHS exposure and HRQOL varied for each of the four diagnoses for baseline health and the acute illness, it is important to note that the point estimates for the adjusted mean differences were uniformly lower for the SHS-exposed children in each subgroup. Even so, only acute illness scores for croup exceeded the MCID threshold.16 Croup is the only included condition of the upper airway and is characterized by laryngotracheal inflammation leading to the typical cough and, in moderate to severe cases, stridor. Given that chronic SHS exposure induces a proinflammatory state,3 it is possible that SHS-exposed children with croup had more severe illness compared with nonexposed children with croup resulting in lower HRQOL scores on admission. Further, perceived differences in illness severity and HRQOL may be more readily apparent in children with croup (eg, stridor at rest vs intermittent or no stridor) as compared with children with lower respiratory tract diseases.

Of the four included diagnoses, the link between SHS exposure and asthma outcomes has been most studied. Prior work has demonstrated more frequent and severe acute exacerbations, as well as worse long-term lung function among SHS-exposed children as compared with nonexposed children.22-24 It was, therefore, surprising that our study failed to demonstrate associations between SHS exposure and HRQOL among children with asthma. Reasons for this finding are unclear. One hypothesis is that caregivers of SHS-exposed children with asthma may be more aware of the impacts of SHS exposure on respiratory health (through prior education) and, thus, more likely to modify their smoking behaviors, or for their children to be on daily asthma controller therapy. Alternatively, caregivers of children with asthma may be more likely to underreport home SHS exposure. Thirty-eight percent of children with asthma, however, were classified as SHS-exposed. This percentage was greater than the other three conditions studied (25%-32%), suggesting that differential bias in underreporting was minimal. Given that children with asthma were older, on average, than children with the other three conditions, it may also be that these children spent more time in smoke-free environments (eg, school).

Nearly one-third of children in our study were exposed to SHS in the home. This is similar to the prevalence of exposure in other studies conducted among hospitalized children8,10,21,25 but higher than the national prevalence of home SHS exposure among children in the United States.26 Thus, hospitalized children represent a particularly vulnerable population and an important target for interventions aiming to reduce exposure to SHS. Although longitudinal interventions are likely necessary to affect long-term success, hospitalization for ARI may serve as a powerful teachable moment to begin cessation efforts. Hospitalization also offers time beyond a typical primary care outpatient encounter to focus on cessation counseling and may be the only opportunity to engage in counseling activities for some families with limited time or access. Further, prior studies have demonstrated both the feasibility and the effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions in hospitalized children.27-30 Unfortunately, however, SHS exposure is often not documented at the time of hospitalization, and many opportunities to intervene are missed.25,31 Thus, there is a need for improved strategies to reliably identify and intervene on SHS-exposed children in the hospital setting.

These findings should be considered in the context of several limitations. The observational nature of our study raises the potential for confounding, specifically with regard to socioeconomic status, as this is associated with both SHS exposure and lower HRQOL. Our modeling approach attempted to control for several factors associated with socioeconomic status, including caregiver education and insurance coverage, but there is potential for residual confounding. No single question is sufficient to fully assess SHS exposure as the intensity of home SHS exposure likely varies widely, and some children may be exposed to SHS outside of the home environment.32 The home, however, is often the most likely source of regular SHS exposure,33,34 especially among young children (our cohort’s mean age was 3.6 years). Misclassification of SHS exposure is also possible due to underreporting of smoking.35,36 As a result, some children regularly exposed to SHS may have been misclassified as nonexposed, and the observed associations between SHS exposure and HRQOL may be underestimated. Confirming our study’s findings using objective assessments of SHS exposure, such as cotinine, are warranted. Given the young age of our cohort, the PedsQL surveys were completed by the parent or legal guardian only in >90% of the enrolled subjects, and caregiver perceptions may not accurately reflect the child’s perceptions. Prior work, however, has demonstrated the validity of parent-proxy reporting of the PedsQL, including correlation with child self-report.37 In our study, correlation between child and caregiver reporting (when available) was also very good (r = 0.72, 95% CI 0.64, 0.77). It is also possible that the timing of the HRQOL assessments (on admission) may have biased perceptions of baseline HRQOL, although we anticipate any bias would likely be nondifferential between SHS-exposed and nonexposed children and across diagnoses.

Nearly one-third of children in our study were exposed to SHS exposure in the home, and SHS exposure was associated with lower HRQOL for baseline health and during acute illness, providing further evidence of the dangers of SHS. Much work is needed in order to eliminate the impact of SHS on child health and families of children hospitalized for respiratory illness should be considered a priority population for smoking cessation efforts.