Home Smoke Exposure and Health-Related Quality of Life in Children with Acute Respiratory Illness

OBJECTIVE: This study aims to assess whether secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure has an impact on health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in children with acute respiratory illness (ARI).

METHODS: This study was nested within a multicenter, prospective cohort study of children (two weeks to 16 years) with ARI (emergency department visits for croup and hospitalizations for croup, asthma, bronchiolitis, and pneumonia) between July 1, 2014 and June 30, 2016. Subjects were surveyed upon enrollment for sociodemographics, healthcare utilization, home SHS exposure (0 or ≥1 smoker in the home), and child HRQOL (Pediatric Quality of Life Physical Functioning Scale) for both baseline health (preceding illness) and acute illness (on admission). Data on insurance status and medical complexity were collected from the Pediatric Hospital Information System database. Multivariable linear mixed regression models examined associations between SHS exposure and HRQOL.

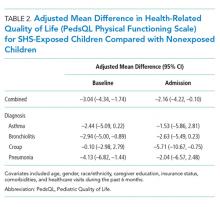

RESULTS: Home SHS exposure was reported in 728 (32%) of the 2,309 included children. Compared with nonexposed children, SHS-exposed children had significantly lower HRQOL scores for baseline health (mean difference –3.04 [95% CI –4.34, –1.74]) and acute illness (–2.16 [–4.22, –0.10]). Associations were strongest among children living with two or more smokers. HRQOL scores were lower among SHS-exposed children for all four conditions but only significant at baseline for bronchiolitis (–2.94 [–5.0, –0.89]) and pneumonia (–4.13 [–6.82, –1.44]) and on admission for croup (–5.71 [–10.67, –0.75]).

CONCLUSIONS: Our study demonstrates an association between regular SHS exposure and decreased HRQOL with a dose-dependent response for children with ARI, providing further evidence of the negative impact of SHS. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2019;14:212-217. © 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Covariates collected at the time of enrollment included sociodemographics (child age, gender, race/ethnicity, and caregiver education), and healthcare utilization (caregiver-reported patient visits to a healthcare provider in the preceding six months). Insurance status and level of medical complexity (using the Pediatric Medical Complexity Algorithm)18 were obtained using the Pediatric Hospital Information System database, an administrative database containing clinical and resource utilization data from >45 children’s hospitals in the United States including all of the PRIMES study hospitals.13

Analysis

Descriptive statistics included frequency (%) and mean (standard deviation). Bivariate comparisons according to SHS exposure status were analyzed using chi-squared tests for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables. Multivariable linear mixed regression models were used to examine associations between home SHS exposure and HRQOL for baseline health and during admission, overall and stratified by diagnosis. Covariates in each model included age, sex, race/ethnicity, caregiver education, and healthcare visits in the preceding six months. We also included a hospital random effect to account for clustering of patients within hospitals and used robust standard errors for inference.

In a secondary analysis to explore potential dose-response effects of SHS exposure, we examined associations between an ordinal exposure variable (0 smokers, 1 smoker, ≥2 smokers) and HRQOL for baseline health and during admission for the acute illness. Because of sample size limitations, diagnosis-specific analyses examining dose-response effects were not conducted.

RESULTS

Study Population

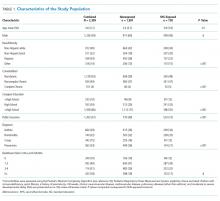

Of the 2,334 children enrolled in the PRIMES study, 25 (1%) respondents did not report on home SHS exposure and were excluded, yielding a final study population of 2,309 children, of whom 728 (32%) had reported home SHS exposure. The study population included 664 children with asthma (mean age seven years [3.5]; 38% with home SHS exposure), 740 with bronchiolitis (mean age 0.7 years [0.5]; 32% with home SHS exposure), 342 with croup (mean age 1.7 [1.1]; 25% with home SHS exposure), and 563 with pneumonia (mean age 4.4 [3.8]; 27% with home SHS exposure; Table 1). Compared with non-SHS-exposed children, those with home SHS exposure tend to be slightly older (3.9 vs 3.4 years, P = .01), more likely to be non-Hispanic Black (29% vs 19%, P < .001), to have a chronic condition (52% vs 41%, P < .001), to come from a household where caregiver(s) did not graduate from college (45% vs 29%, P < .001), and to have public insurance (73% vs 49%, P < .001).

Home SHS Exposure and Health-related Quality of Life

The overall mean HRQOL score for baseline health was 83 (15), with a range across diagnoses of 82 to 87. Compared with non-SHS-exposed children, children with home SHS exposure had a lower mean HRQOL score for baseline health (adjusted mean difference –3.04 [95% CI -4.34, –1.74]). In analyses stratified by diagnosis, baseline health scores were lower for SHS-exposed children for all four conditions, but differences were statistically significant only for bronchiolitis (adjusted mean difference –2.94 [–5.0, –0.89]) and pneumonia (adjusted mean value –4.13 [–6.82, –1.44]; Table 2); none of these differences met the MCID threshold.