Association between Hospitalist Productivity Payments and High-Value Care Culture

BACKGROUND: Given the national emphasis on affordability, healthcare systems expect that their clinicians are motivated to provide high-value care. However, some hospitalists are reimbursed with productivity bonuses and little is known about the effects of these reimbursements on the local culture of high-value care delivery.

OBJECTIVE: To evaluate if hospitalist reimbursement models are associated with high-value culture in university, community, and safety-net hospitals.

DESIGN, PATIENTS, AND SETTINGS: Internal medicine hospitalists from 12 hospitals across California completed a cross-sectional survey assessing their perceptions of high-value care culture within their institutions. Sites represented university, community, and safety-net centers with different performances as reflected by the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Service’s Value-based Purchasing (VBP) scores.

MEASUREMENT: Demographic characteristics and High-Value Care Culture Survey (HVCCSTM) scores were evaluated using descriptive statistics, and associations were assessed through multilevel linear regression.

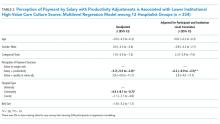

RESULTS: Of the 255 hospitalists surveyed, 147 (57.6%) worked in university hospitals, 85 (33.3%) in community hospitals, and 23 (9.0%) in safety-net hospitals. Across all 12 sites, 166 (65.1%) hospitalists reported payment with salary or wages, and 77 (30.2%) with salary plus productivity adjustments. The mean HVCCS score was 50.2 (SD 13.6) on a 0-100 scale. Hospitalists reported lower mean HVCCS scores if they reported payment with salary plus productivity (β = −6.2, 95% CI −9.9 to −2.5) than if they reported payment with salary or wages.

CONCLUSIONS: Hospitalists paid with salary plus productivity reported lower high-value care culture scores for their institutions than those paid with salary or wages. High-value care culture and clinician reimbursement schemes are potential targets of strategies for improving quality outcomes at low cost.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Hospital Characteristics

Of the 12 study sites, four from each type of hospital (ie, safety-net based, community based, and university based) and four representing each value-based purchasing performance tertile (ie, high, middle, and low) were included. Eleven (91.7%) sites were located in urban areas with an average DSH index of 0.40 (SD 0.23), case mix index of 1.97 (SD 0.28), and bed size of 435.5 (SD 146.0; Table 1).

In multilevel regression modeling across all 12 sites, hospitalists from community-based hospitalist programs reported lower mean HVCCS scores (β = −4.4, 95% CI −8.1 to −0.7; Table 2) than those from other hospital types.

High-Value Care Culture Survey Scores

The mean HVCCS score was 50.2 (SD 13.6), and mean domain scores across all sites were 65.4 (SD 15.6) for leadership and health system messaging, 32.4 (SD 22.8) for data transparency and access, 52.1 (SD 19.7) for comfort with cost conversations, and 50.7 (SD 21.4) for blame-free environment (Table 1). For the majority (two-thirds) of individual HVCCS items, more than 30% of hospitalists across all sites agreed or strongly agreed that components of a low-value care culture exist within their institutions. For example, over 80% of hospitalists reported low transparency and limited access to data (see Appendix I for complete survey responses).

Hospitalists reported different HVCCS domains as strengths or weaknesses within their institutions in accordance with hospital type. Compared with university-based and safety-net-based hospitalists, community-based hospitalists reported lower scores in having a blame-free environment (466, SD 21.8). Nearly 50% reported that the clinicians’ fear of legal repercussions affects their frequency of ordering unneeded tests or procedures, and 30% reported that individual clinicians are blamed for complications. Nearly 40% reported that clinicians are uncomfortable discussing the costs of tests or treatments with patients and reported that clinicians do not feel that physicians should discuss costs with patients. Notably, community-based hospitalists uniquely differed in how they reported components of leadership and health system messaging. Over 60% reported a work climate or role modeling supportive of delivering quality care at lower costs. Only 48%, however, reported success seen from implemented efforts, and 45% reported weighing costs in clinical decision making (Table 1, Appendix I).

University-based hospitalists had significantly higher scores in leadership and health system messaging (67.4, SD 16.9) than community-based and safety-net-based hospitalists. They reported that their institutions consider their suggestions to improve quality care at low cost (75%), openly discuss ways to deliver this care (64%), and are actively implementing projects (73%). However, only 54% reported seeing success from implemented high-value care efforts (Table 1, Appendix I).

Safety-net hospitalists reported lower scores in leadership and health system messaging (56.8, SD 10.5) than university-based and community-based hospitalists. Few hospitalists reported a work climate (26%) or role modeling (30%) that is supportive of delivering quality care at low costs, openly discusses ways to deliver this care (35%), encourages frontline clinicians to pursue improvement projects (57%), or actively implements projects (26%). They also reported higher scores in the blame-free environment domain (59.8, SD 22.3; Table 1; Appendix 1).