So Much More than Bald and Bloated

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

He was initially treated empirically with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) with minimal improvement. He received additional immunomodulating therapies including methylprednisolone, plasmapheresis, and rituximab but did not tolerate a trial of mycophenolate. Six weeks after therapy initiation, his antibody titers decreased to 0.89 nmol/L with associated clinical improvement. Ultimately, he was discharged from the hospital on day 73 with a feeding tube and supplemental total parenteral nutrition. Four months postdischarge, he had returned to his prediagnosis weight, had eased back into his prior activities, and was off supplemental nutrition. Over a year later, he completed a 10-month prednisone taper and continued to receive monthly IVIG infusion

DISCUSSION

The clinical approach to dysautonomia is based on different etiologies: (1) those associated with neurodegenerative disorders; (2) those associated with peripheral neuropathies, and (3) isolated autonomic failure.2 Thus, clinical history and physical examination can assist greatly in guiding the evaluation of patients. Neurodegenerative disorders (such as Parkinson disease), combined disorders (such as multiple-system atrophy), and acquired or familial processes were considered. Our patient had neither a personal or family history nor physical examination supporting a neurodegenerative disorder. Disorders of the peripheral nerves were considered and can broadly be categorized as chronic sensorimotor neuropathies, sensory ganglionopathies, distal painful neuropathies, and acute or subacute motor polyradiculopathies. During evaluation, no historical, physical examination, or laboratory findings supported diabetes, amyloidosis, heavy metals, Sjögren syndrome, paraneoplastic neuropathy, sodium channel disorders, infectious etiologies, or porphyria (Table 1). Thus, in the absence of supportive evidence for primary neurodegenerative disorders or peripheral neuropathies, his syndrome appeared most compatible with an isolated autonomic failure syndrome. The principal differential for this syndrome is pure autonomic failure versus an immune-mediated autonomic disorder, including paraneoplastic autoimmune neuropathy and AAG. The diagnosis of pure autonomic failure is made after there is no clear unifying syndrome after more than five years of investigation. After exploration, no evidence of malignancy was discovered on body cross sectional imaging, PET scanning, bone marrow biopsy, colonoscopy, or laboratory testing. Thus, positive serologic testing in the absence of an underlying malignancy suggests a diagnosis of AAG.

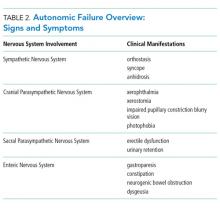

AAG was first described in 1969 and is a rare, acquired disorder characterized by combined failure of the parasympathetic, sympathetic, and enteric nervous systems. This disorder typically presents in young-to-middle aged patients but has been described in all age groups. It is more commonly seen in patients with coexistent autoimmune diseases and/or a history of familial autoimmunity. The onset of clinical AAG may be subacute (less than three months) or insidious (more than three months). Patients present with signs or symptoms of pandysautonomia, such as severe orthostatic hypotension, syncope, constipation and gastrointestinal dysmotility, urinary retention, fixed and dilated pupils, and dry mouth and eyes (Table 2). Up to 40% of patients with AAG may also have significant cognitive impairment.3,4 Diagnosis relies on a combination of typical clinical features as discussed above and the exclusion of other diagnostic considerations. Diagnosis of AAG is aided by the presence of autoantibodies to ganglionic nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (gnAChR), particularly antiganglionic acetylcholine receptor α3 (anti-α3gAChR).1 Anti-gnAChR antibodies are only present in about half of patients with AAG. Antibody titers are highest in subacute AAG (40%-50%)3 compared with chronic AAG (30%-40%) or paraneoplastic AAG (10%-20%).5 Anti-gnAChR antibodies are not specific to AAG and have been identified in low levels in up to 20% of patients with thymomas, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, chronic idiopathic anhidrosis, idiopathic gastrointestinal dysmotility, Lambert–Eaton syndrome, and myasthenia gravis without thymoma.1,5-7 These associations raise the question of shared pathology and perhaps a syndrome overlap. Individuals with seropositive AAG may also have other paraneoplastic antibodies, making it clinically indistinguishable from paraneoplastic autonomic neuropathy.5,8 Although the autoantibody lacks sensitivity and is imperfectly specific, its presence supports a diagnosis of AAG. Anti-gnAChR antibodies have been shown to be pathological in rabbit and mouse models.4 In patients with AAG, higher autoantibody titers correlate with increased disease severity.1,6,7 A decrease in autoantibody titers correlates with decreased disease severity.6 Case report series also described a distinct entity of seronegative AAG.2,3 Maintaining a high clinical suspicion for AAG even with negative antibodies is important.

Given the rarity of the disease, no standard therapeutic regimens are available. About one-third of individuals improve on their own, while other individuals require extensive immunomodulation and symptom management. Case series and observational trials currently make up the vast array of treatment data. Therapies include glucocorticoids, plasmapheresis, IVIG, and other immunosuppressive agents, such as rituximab.9-12 Patients with and without identified anti-gnAChRs antibodies may respond to therapy.12 The overall long-term prognosis of the disease is poorly characterized.9,10,13

Despite the rarity of the syndrome discussed, this case represents how diagnostic reasoning strategies, such as law of parsimony, shift how the case is framed. For example, a middle-aged man with several new, distinctly unrelated diagnoses versus a middle-aged man with signs and symptoms of autonomic failure alters the subsequent clinical reasoning and diagnostic approach. Many diseases, both common and rare, are associated with dysautonomia. Therefore, clinicians should have an approach to autonomic failure