So Much More than Bald and Bloated

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

His newly reported erectile dysfunction suggests the possibility of a psychiatric, neurologic, hormonal, or vascular process and should be explored further. Sexual dysfunction is also associated with adrenal insufficiency and hypopituitarism. However, the presence of suspected prostatic hypertrophy in a male competitive athlete in his forties also raises the question of exogenous androgen use.

His past medical history was notable for a two-year history of alopecia totalis, seasonal allergies, asthma, and a repaired congenital aortic web with known aortic insufficiency. He was married with two children, worked an office job, and had no history of injection drug use, blood transfusions, or multiple sexual partners. His family history was notable for hypothyroidism and asthma in several family members in addition to Crohn disease, celiac disease, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancers of the breast and lung.

His past medical, surgical, and family history supports a diagnosis of autoimmune disease. Although there is a personal and family history of atopic disorders, including allergic rhinitis and asthma, no association is found between atopy and autoimmunity. His family history of hypothyroidism, Crohn disease, and diabetes suggests a familial autoimmune genetic predisposition. His history of alopecia totalis in the setting of hypothyroidism and possible autoimmune adrenal insufficiency or autoimmune hypophysitis raises suspicion for the previously suggested diagnosis of polyglandular autoimmune syndrome, also known as autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome. Type I polyglandular autoimmune syndrome is associated with hypoparathyroidism and mucocutaneous candidiasis. In the absence of these symptoms, the patient more likely has type II polyglandular autoimmune syndrome. Type II syndrome is more prevalent and can occur in the setting of other nonendocrine autoimmune disorders, such as vitiligo, myasthenia gravis, or rheumatoid arthritis. Adrenal insufficiency can be the initial and most prominent manifestation of type II syndrome.

On physical exam, he was afebrile, with a heart rate of 68 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 16 breaths per minute, and normal oxygen saturation. His supine blood pressure and heart rate were 116/72 mm Hg and 66 beats per minute, respectively, and his standing blood pressure and heart rates were 80/48 mm Hg and 68 beats per minute respectively. He was thin, had diffuse scalp and body alopecia, and was ill-appearing with dry skin and dry mucous membranes. No evidence of Osler nodes, Janeway lesions, or splinter hemorrhages were found on cutaneous examination. No Roth spots or conjunctival hemorrhages were noted on ophthalmologic examination. He had both a 3/6 crescendo–decrescendo systolic murmur best heard at the right clavicle and radiated to the carotids and a 3/6 early diastolic decrescendo murmur best heard at the left sternal border. His abdomen was slightly protuberant, with reduced bowel sounds, hyperresonant to tympanitic on percussion, and a diffusely, moderately tender without peritoneal signs. Neurologic examination revealed 8 mm pupils with minimal response to light and accommodation. The remaining portions of his cranial nerve and complete neurologic examination were normal.

The presence of postural hypotension supports the previous suspicion of adrenal insufficiency, and the possibility of a pituitary or hypothalamic process remains. However, his dilated and minimally responsive pupils and potentially adynamic bowel are inconsistent with these diagnoses. Mydriasis and adynamic bowel in combination with orthostatic hypotension, dysgeusia, urinary retention, and erectile dysfunction are strongly suggestive of an autonomic process. Endocarditis is worth considering given his multisystem involvement, subacute decline, and known valve pathology. The absence of fever or stigmata of endocarditis make it difficult to explain his clinical syndrome. An echocardiogram would be reasonable for further assessment. At this point, it is prudent to explore his adrenal and pituitary function; if unrevealing, embark on an evaluation of his autonomic dysfunction.

Initial laboratory investigations were notable for mild normocytic anemia and hypoalbuminemia. His cosyntropin stimulation test was normal at 60 minutes. An abdominal CT scan demonstrated marked dilation in the small bowel loops (6 cm in caliber) with associated small bowel wall thickening and hyperemia. The echocardiogram was unrevealing and only confirmed the ongoing, progression of his known valve pathology without evidence of vegetation.

The above testing rules out primary adrenal insufficiency, but an appropriate response to the cosyntropin stimulation test does not rule out secondary, or pituitary, adrenal insufficiency. The echocardiogram and lack of other features make infective endocarditis unlikely. Thus, as mentioned, it is important now to commence a complete work-up of his probable dysautonomia to explain the majority of his features. Additionally, his hypothyroidism (if more than sick euthyroid syndrome), family history of autoimmune processes, and alopecia totalis all suggest the possibility of an immune-related syndrome. His CT scan revealed some thickened hyperemic bowel, which could suggest an IBD, such as Crohn disease; however, the absence of other signs, such as fever, diarrhea, or bloody stools, argues against this diagnosis. A syndrome that could unify his presentation is autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy (AAG), a rare genetic autonomic system disorder that presents with pandysautonomia. The spectrum of autoimmunity was considered early in this case, but the differential diagnosis included more common conditions, such as adrenal insufficiency. Similarly, IBD remains a consideration. The serologic studies for IBD can be useful but they lack definitive diagnostic accuracy. Given that treatment for AAG differs from that for IBD, additional information will help guide the therapeutic approach. Anti-α3gnAChR antibodies, which are associated with AAG, should be checked.

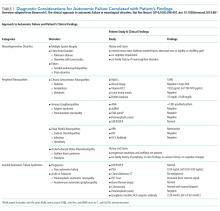

His history of presyncope, anhidrosis, urinary retention, and ileus raised suspicion for pandysautonomia, as characterized by signs of sympathetic and parasympathetic dysfunction. The suspicion for pandysautonomia was confirmed via specialized autonomic testing, which included reduced heart rate variation on Valsalva and deep breathing maneuvers, orthostatic hypotension consistent autonomic insufficiency on Tilt table testing, and reduced sweat response to acetylcholine application (QSART test). The patient underwent further diagnostic serologic testing to differentiate causes of autonomic failure (Table 1). His personal and family history of autoimmunity led to the working diagnosis of AAG. Ultimate testing revealed high titers of autoantibodies, specifically anti-α3gnAChR (3.29 nmol/L, normal <0.02 nmol/L), directed against the ganglionic nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. This finding strongly supported the diagnosis of AAG.1,4-7