Is Posthospital Syndrome a Result of Hospitalization-Induced Allostatic Overload?

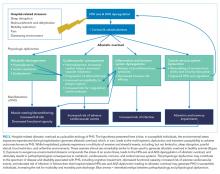

After discharge from the hospital, patients face a transient period of generalized susceptibility to disease as well as an elevated risk for adverse events, including hospital readmission and death. The term posthospital syndrome (PHS) has been used to describe this time of enhanced vulnerability. Based on data from bench to bedside, this narrative review examines the hypothesis that hospital-related allostatic overload is a plausible etiology of PHS. Resulting from extended exposure to stress, allostatic overload is a maladaptive state driven by overuse and dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the autonomic nervous system that ultimately generates pathophysiologic consequences to multiple organ systems. Markers of allostatic overload, including elevated levels of cortisol, catecholamines, and inflammatory markers, have been associated with adverse outcomes after hospital discharge. Based on the evidence, we suggest a possible mechanism for postdischarge vulnerability, encourage critical contemplation of traditional hospital environments, and suggest interventions that might improve outcomes.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

IMPLICATIONS AND NEXT STEPS

A large body of evidence stretching from bench to bedside suggests that environmental stressors associated with hospitalization are toxic. Understanding PHS within the context of hospital-induced allostatic overload presents a unifying theory for the interrelated multisystem dysfunction and increased susceptibility to adverse events that patients experience after discharge (Figure 2). Furthermore, it defines a potential pathophysiological mechanism for the cognitive impairment, elevated cardiovascular risk, immune system dysfunction, metabolic derangements, and functional decline associated with PHS. Additionally, this theory highlights environmental interventions to limit PHS development and suggests mechanisms to promote stress resilience. Although it is difficult to disentangle the consequences of the endogenous stress triggered by an acute illness from the exogenous stressors related to hospitalization, it is likely that the 2 simultaneous exposures compound risk for stress system dysregulation and allostatic overload. Moreover, hospitalized patients with preexisting HPA axis dysfunction at baseline from chronic disease or advancing age may be even more susceptible to these adverse outcomes. If this hypothesis is true, a reduction in PHS would require mitigation of the modifiable environmental stressors encountered by patients during hospitalization. Directed efforts to diminish ambient noise, limit nighttime disruptions, thoughtfully plan procedures, consider ongoing nutritional status, and promote opportunities for patients to exert some control over their environment may diminish the burden of extrinsic stressors encountered by all patients in the hospital and improve outcomes after discharge.

Hospitals are increasingly recognizing the importance of improving patients’ experience of hospitalization by reducing exposure to potential toxicities. For example, many hospitals are now attempting to reduce sleep disturbances and sleep latency through reduced nighttime noise and light levels, fewer nighttime interruptions for vital signs checks and medication administration, and commonsensical interventions like massages, herbal teas, and warm milk prior to bedtime.89 Likewise, intensive care units are targeting environmental and physical stressors with a multifaceted approach to decrease sedative use, promote healthy sleep cycles, and encourage exercise and ambulation even in those patients who are mechanically ventilated.30 Another promising development has been the increase of Hospital at Home programs. In these programs, patients who meet the criteria for inpatient admission are instead comprehensively managed at home for their acute illness through a multidisciplinary effort between physicians, nurses, social workers, physical therapists, and others. Patients hospitalized at home report higher levels of satisfaction and have modest functional gains, improved health-related quality of life, and decreased risk of mortality at 6 months compared with hospitalized patients.90,91 With some admitting diagnoses (eg, heart failure), hospitalization at home may be associated with decreased readmission risk.92 Although not yet investigated on a physiologic level, perhaps the benefits of hospital at home are partially due to the dramatic difference in exposure to environmental stressors.

A tool that quantifies hospital-associated stress may help health providers appreciate the experience of patients and better target interventions to aspects of their structure and process that contribute to allostatic overload. Importantly, allostatic overload cannot be identified by one biomarker of stress but instead requires evidence of dysregulation across inflammatory, neuroendocrine, hormonal, and cardiometabolic systems. Future studies to address the burden of stress faced by hospitalized patients should consider a summative measure of multisystem dysregulation as opposed to isolated assessments of individual biomarkers. Allostatic load has previously been operationalized as the summation of a variety of hemodynamic, hormonal, and metabolic factors, including blood pressure, lipid profile, glycosylated hemoglobin, cortisol, catecholamine levels, and inflammatory markers.93 To develop a hospital-associated allostatic load index, models should ideally be adjusted for acute illness severity, patient-reported stress, and capacity for stress resilience. This tool could then be used to quantify hospitalization-related allostatic load and identify those at greatest risk for adverse events after discharge, as well as measure the effectiveness of strategic environmental interventions (Table 2). A natural first experiment may be a comparison of the allostatic load of hospitalized patients versus those hospitalized at home.

The risk of adverse outcomes after discharge is likely a function of the vulnerability of the patient and the degree to which the patient’s healthcare team and social support network mitigates this vulnerability. That is, there is a risk that a person struggles in the postdischarge period and, in many circumstances, a strong healthcare team and social network can identify health problems early and prevent them from progressing to the point that they require hospitalization.13,94-96 There are also hospital occurrences, outside of allostatic load, that can lead to complications that lengthen the stay, weaken the patient, and directly contribute to subsequent vulnerability.94,97 Our contention is that the allostatic load of hospitalization, which may also vary by patient depending on the circumstances of hospitalization, is just one contributor, albeit potentially an important one, to vulnerability to medical problems after discharge.

In conclusion, a plausible etiology of PHS is the maladaptive mind-body consequences of common stressors during hospitalization that compound the stress of acute illness and produce allostatic overload. This stress-induced dysfunction potentially contributes to a spectrum of generalized disease susceptibility and risk of adverse outcomes after discharge. Focused efforts to diminish patient exposure to hospital-related stressors during and after hospitalization might diminish the presence or severity of PHS. Viewing PHS from this perspective enables the development of hypothesis-driven risk-prediction models, encourages critical contemplation of traditional hospitalization, and suggests that targeted environmental interventions may significantly reduce adverse outcomes.