Is Posthospital Syndrome a Result of Hospitalization-Induced Allostatic Overload?

After discharge from the hospital, patients face a transient period of generalized susceptibility to disease as well as an elevated risk for adverse events, including hospital readmission and death. The term posthospital syndrome (PHS) has been used to describe this time of enhanced vulnerability. Based on data from bench to bedside, this narrative review examines the hypothesis that hospital-related allostatic overload is a plausible etiology of PHS. Resulting from extended exposure to stress, allostatic overload is a maladaptive state driven by overuse and dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the autonomic nervous system that ultimately generates pathophysiologic consequences to multiple organ systems. Markers of allostatic overload, including elevated levels of cortisol, catecholamines, and inflammatory markers, have been associated with adverse outcomes after hospital discharge. Based on the evidence, we suggest a possible mechanism for postdischarge vulnerability, encourage critical contemplation of traditional hospital environments, and suggest interventions that might improve outcomes.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

IMPACT OF ALLOSTATIC OVERLOAD ON PHYSIOLOGIC FUNCTION

Animal Models of Stress

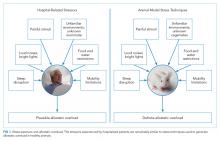

Laboratory techniques reminiscent of the numerous environmental stressors associated with hospitalization have been used to reliably trigger allostatic overload in healthy young animals.51 These techniques include sequential exposure to aversive stimuli, including food and water deprivation, continuous overnight illumination, paired housing with known and unknown cagemates, mobility restriction, soiled cage conditions, and continuous noise. All of these techniques have been shown to cause HPA axis and ANS dysfunction, allostatic overload, and subsequent stress-mediated consequences to multiple organ systems.19,52-54 Given the remarkable similarity of these protocols to common experiences during hospitalization, animal models of stress may be useful in understanding the spectrum of maladaptive consequences experienced by patients within the hospital (Figure 1).

These animal models of stress have resulted in a number of instructive findings. For example, in rodents, extended stress exposure induces structural and functional remodeling of neuronal networks that precipitate learning and memory, working memory, and attention impairments.55-57 These exposures also result in cardiovascular abnormalities, including dyslipidemia, progressive atherosclerosis,58,59 and enhanced inflammatory cytokine expression,60 all of which increase both atherosclerotic burden and susceptibility to plaque rupture, leading to elevated risk for major cardiovascular adverse events. Moreover, these extended stress exposures in animals increase susceptibility to both bacterial and viral infections and increase their severity.16,61 This outcome appears to be driven by a stress-induced elevation of glucocorticoid levels, decreased leukocyte proliferation, altered leukocyte trafficking, and a transition to a proinflammatory cytokine environment.16, 61 Allostatic overload has also been shown to contribute to metabolic dysregulation involving insulin resistance, persistence of hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, catabolism of lean muscle, and visceral adipose tissue deposition.62-64 In addition to cardiovascular, immune, and metabolic consequences of allostatic overload, the spectrum of physiologic dysfunction in animal models is broad and includes mood disorder symptoms,65 intestinal barrier abnormalities,66 airway reactivity exacerbation,67 and enhanced tumor growth.68

Although the majority of this research highlights the multisystem effects of variable stress exposure in healthy animals, preliminary evidence suggests that aged or diseased animals subjected to additional stressors display a heightened inflammatory cytokine response that contributes to exaggerated sickness behavior and greater and prolonged cognitive deficits.69 Future studies exploring the consequences of extended stress exposure in animals with existing disease or debility may therefore more closely simulate the experience of hospitalized patients and perhaps further our understanding of PHS.

Hospitalized Patients

While no intervention studies have examined the effects of potential hospital stressors on the development of allostatic overload, there is evidence from small studies that dysregulated stress responses during hospitalization are associated with adverse events. For example, high serum cortisol, catecholamine, and proinflammatory cytokine levels during hospitalization have individually been associated with the development of cognitive dysfunction,70-72 increased risk of cardiovascular events such as myocardial infarction and stroke in the year following discharge,73-76 and the development of wound infections after discharge.77 Moreover, elevated plasma glucose during admission for myocardial infarction in patients with or without diabetes has been associated with greater in-hospital and 1-year mortality,78 with a similar relationship seen between elevated plasma glucose and survival after admission for stroke79 and pneumonia.80 Furthermore, in addition to atherothrombosis, stress may contribute to the risk for venous thromboembolism,81 resulting in readmissions for deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism posthospitalization. Although potentially surrogate markers of illness acuity, a handful of studies have shown that these stress biomarkers are actually only weakly correlated with,82 or independent of,72,76 disease severity. As discussed in detail below, future studies utilizing a summative measure of multisystem physiologic dysfunction as opposed to individual biomarkers may more accurately reflect the cumulative stress effects of hospitalization and subsequent risk for adverse events.

Additional Considerations

Elderly patients, in particular, may have heightened susceptibility to the consequences of allostatic overload due to common geriatric issues such as multimorbidity and frailty. Patients with chronic diseases display both baseline HPA axis abnormalities as well as dysregulated stress responses and may therefore be more vulnerable to hospitalization-related stress. For example, when subjected to psychosocial stress, patients with chronic conditions such as diabetes, heart failure, or atherosclerosis demonstrate elevated cortisol levels, increased circulating markers of inflammation, as well as prolonged hemodynamic recovery after stress resolution compared with normal controls.83-85 Additionally, frailty may affect an individual’s susceptibility to exogenous stress. Indeed, frailty identified on hospital admission increases the risk for adverse outcomes during hospitalization and postdischarge.86 Although the specific etiology of this relationship is unclear, persons with frailty are known to have elevated levels of cortisol and other inflammatory markers,87,88 which may contribute to adverse outcomes in the face of additional stressors.