Improving Teamwork and Patient Outcomes with Daily Structured Interdisciplinary Bedside Rounds: A Multimethod Evaluation

BACKGROUND: Previous research has shown that interdisciplinary ward rounds have the potential to improve team functioning and patient outcomes.

DESIGN: A convergent parallel multimethod approach to evaluate a hospital interdisciplinary ward round intervention and ward restructure.

SETTING: An acute medical unit in a large tertiary care hospital in regional Australia.

PARTICIPANTS: Thirty-two clinicians and inpatients aged 15 years and above, with acute episode of care, discharged during the year prior and the year of the intervention.

INTERVENTION: A daily structured interdisciplinary bedside round combined with a ward restructure.

MEASUREMENTS: Qualitative measures included contextual factors and measures of change and experiences of clinicians. Quantitative measures included length of stay (LOS), monthly “calls for clinical review,’” and cost of care delivery.

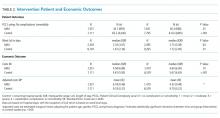

RESULTS: Clinicians reported improved teamwork, communication, and understanding between and within the clinical professions, and between clinicians and patients, after the intervention implementation. There was no statistically significant difference between the intervention and control wards in the change in LOS over time (Wald χ2 = 1.05; degrees of freedom [df] = 1; P = .31), but a statistically significant interaction for cost of stay, with a drop in cost over time, was observed in the intervention group, and an increase was observed in the control wards (Wald χ2 = 6.34; df = 1; P = .012). The medical wards and control wards differed significantly in how the number of monthly “calls for clinical review” changed from prestructured interdisciplinary bedside round (SIBR) to during SIBR (F (1,44) = 12.18; P = .001).

CONCLUSIONS: Multimethod evaluations are necessary to provide insight into the contextual factors that contribute to a successful intervention and improved clinical outcomes.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Consequences

All interviewees lauded the benefits of the SIBR intervention for patients. Patients were perceived to be better informed and more respected, and they benefited from greater perceived timeliness of treatment and discharge, easier access to doctors, better continuity of treatment and outcomes, improved nurse knowledge of their circumstances, and fewer gaps in their care. Clinicians spoke directly to the patient during SIBR, rather than consulting with professional colleagues over the patient’s head. Some staff felt that doctors were now thinking of patients as “people” rather than “a set of symptoms.” Nurses discovered that informed patients are easier to manage.

Staff members were prepared to compromise on their own needs in the interests of the patient. The emphasis on the patient during rounds resulted in improved advocacy behaviors of clinicians. The nurses became more empowered and able to show greater initiative. Families appeared to find it much easier to access the doctors and obtain information about the patient, resulting in less distress and a greater sense of control and trust in the process.

Quantitative Evaluation of the Intervention

Hospital Outcomes

Patient demographics did not change over time within either the AMU or control wards. However, there were significant increases in Patient Clinical Complexity Level (PCCL) ratings for both the AMU (44.7% to 40.3%; P<0.05) and the control wards (65.2% to 61.6%; P < .001). There was not a statistically significant shift over time in median LoS on the ward prior to (2.16 days, IQR 3.07) and during SIBR in the AMU (2.15 days; IQR 3.28), while LoS increased in the control (pre-SIBR: 1.67, 2.34; during SIBR 1.73, 2.40; M-W U z = -2.46, P = .014). Mortality rates were stable across time for both the AMU (pre-SIBR 2.6% [95% confidence interval {CI}, 1.9-3.5]; during SIBR 2.8% [95% CI, 2.1-3.7]) and the control (pre-SIBR 1.3% [95% CI, 1.0-1.5]; during SIBR 1.2% [95% CI, 1.0-1.4]).

The total number of “clinical response calls” or “flags” per month dropped significantly from pre-SIBR to during SIBR for the AMU from a mean of 63.1 (standard deviation 15.1) to 31.5 (10.8), but remained relatively stable in the control (pre-SIBR 72.5 [17.6]; during SIBR 74.0 [28.3]), and this difference was statistically significant (F (1,44) = 9.03; P = .004). There was no change in monthly “red flags” or “rapid response calls” over time (AMU: 10.5 [3.6] to 9.1 [4.7]; control: 40.3 [11.7] to 41.8 [10.8]). The change in total “clinical response calls” over time was attributable to the “yellow flags” or the decline in “calls for clinical review” in the AMU (from 52.6 [13.5] to 22.4 [9.2]). The average monthly “yellow flags” remained stable in the control (pre-SIBR 32.2 [11.6]; during SIBR 32.3 [22.4]). The AMU and the control wards differed significantly in how the number of monthly “calls for clinical review” changed from pre-SIBR to during SIBR (F (1,44) = 12.18; P = .001).

The 2 main outcome measures, LOS and costs, were analyzed to determine whether changes over time differed between the AMU and the control wards after accounting for age, gender, and PCCL. There was no statistically significant difference between the AMU and control wards in terms of change in LOS over time (Wald χ2 = 1.05; degrees of freedom [df] = 1; P = .31). There was a statistically significant interaction for cost of stay, indicating that ward types differed in how they changed over time (with a drop in cost over time observed in the AMU and an increase observed in the control) (Wald χ2 = 6.34; df = 1; P = .012.

DISCUSSION

We report on the implementation of an AMU model of care, including the reorganization of a nursing unit, implementation of IDR, and geographical localization. Our study design allowed a more comprehensive assessment of the implementation of system redesign to include provider perceptions and clinical outcomes.

The 2 very different cultures of the old wards that were combined into the AMU, as well as the fact that the teams had not previously worked together, made the merger of the 2 wards difficult. Historically, the 2 teams had worked in very different ways, and this created barriers to implementation. The SIBR also demanded new ways of working closely with other disciplines, which disrupted older clinical cultures and relationships. While organizational culture is often discussed, and even measured, the full impact of cultural factors when making workplace changes is frequently underestimated.21 The development of a new culture takes time, and it can lag organizational structural changes by months or even years.22 As our interviewees expressed, often emotionally, there was a sense of loss during the merger of the 2 units. While this is a potential consequence of any large organizational change, it could be addressed during the planning stages, prior to implementation, by acknowledging and perhaps honoring what is being left behind. It is safe to assume that future units implementing the rounding intervention will not fully realize commensurate levels of culture change until well after the structural and process changes are finalized, and only then if explicit effort is made to engender cultural change.

Overall, however, the interviewees perceived that the SIBR intervention led to improved teamwork and team functioning. These improvements were thought to benefit task performance and patient safety. Our study is consistent with other research in the literature that reported that greater staff empowerment and commitment is associated with interdisciplinary patient care interventions in front line caregiving teams.23,24 The perception of a more equal nurse-physician relationship resulted in improved job satisfaction, better interprofessional relationships, and perceived improvements in patient care. A flatter power gradient across professions and increased interdisciplinary teamwork has been shown to be associated with improved patient outcomes.25,26

Changes to clinician workflow can significantly impact the introduction of new models of care. A mandated time each day for structured rounds meant less flexibility in workflow for clinicians and made greater demands on their time management and communication skills. Furthermore, the need for human resource negotiations with nurse representatives was an unexpected component of successfully introducing the changes to workflow. Once the benefits of saved time and better communication became evident, changes to workflow were generally accepted. These challenges can be managed if stakeholders are engaged and supportive of the changes.13

Finally, our findings emphasize the importance of combining qualitative and quantitative data when evaluating an intervention. In this case, the qualitative outcomes that include “intangible” positive effects, such as cultural change and improved staff understanding of one another’s roles, might encourage us to continue with the SIBR intervention, which would allow more time to see if the trend of reduced LOS identified in the statistical analysis would translate to a significant effect over time.

We are unable to identify which aspects of the intervention led to the greatest impact on our outcomes. A recent study found that interdisciplinary rounds had no impact on patients’ perceptions of shared decision-making or care satisfaction.27 Although our findings indicated many potential benefits for patients, we were not able to interview patients or their carers to confirm these findings. In addition, we do not have any patient-centered outcomes, which would be important to consider in future work. Although our data on clinical response calls might be seen as a proxy for adverse events, we do not have data on adverse events or errors, and these are important to consider in future work. Finally, our findings are based on data from a single institution.