Tissue Isn’t the Issue

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through the presentation of an actual patient’s case in an approach typical of a morning report. Similar to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician, who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

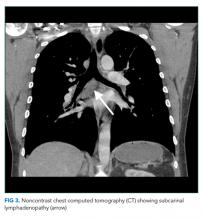

The most likely diagnosis is Löfgren’s syndrome, a variant of sarcoidosis characterized by erythema nodosum, bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, and polyarthralgias or polyarthritis. Löfgren’s syndrome may include fevers, uveitis, widespread skin lesions and other systemic manifestations. Sarcoidosis could explain the lacrimal gland lesion, and could manifest with recurrent kidney stones. Oral lesions may occur in sarcoidosis. A normal serum ACE level may be observed in up to half of patients. The lack of visualized granulomas on the submental node FNA may reflect sampling error, lower likelihood of visualizing granulomas on FNA (compared with excisional biopsy), or biopsy location (hilar nodes are more likely to demonstrate sarcoid granulomas).

Although Löfgren’s syndrome is often self-limited, treatment can ameliorate symptoms. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication can be tried first, with prednisone reserved for refractory cases.

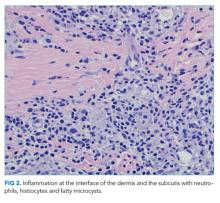

The constellation of bilateral hilar adenopathy, arthritis, and erythema nodosum was consistent with Löfgren’s syndrome, further supported by granulomatous infiltrates on biopsy. The patient’s symptoms resolved with naproxen. He was scheduled for follow-up in dermatology and rheumatology clinics and was referred to hepatology for management of hepatitis C.

COMMENTARY

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of unclear etiology. The disease derives its name from Boeck’s 1899 report describing benign cutaneous lesions that resembled sarcomas.1 Sarcoidosis most commonly manifests as bilateral hilar adenopathy and pulmonary infiltrates, but may impact any tissue or organ, including the eyes, nonhilar lymph nodes, liver, spleen, joints, mucous membranes, and skin. Nephrolithiasis may result from hypercalcemia and/or hypercalciuria (related to granulomatous production of 1,25 vitamin D) and can be the presenting feature of sarcoidosis.2 Less common presentations include neurologic sarcoidosis (which can present with seizures, aseptic meningitis, encephalopathy, neuroendocrine dysfunction, myelopathy and peripheral neuropathies), cardiac sarcoidosis (which may present with arrhythmias, valvular dysfunction, heart failure, ischemia, or pericardial disease), and Heerfordt syndrome (the constellation of parotid gland enlargement, facial palsy, anterior uveitis, and fever). Sarcoidosis may mimic other diseases, including malignancy, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and infiltrative tuberculosis.3 Sarcoidosis-like reactions have occurred in response to malignancy and medications.4

The patient’s rash demonstrated a predilection for areas of prior scarring, which has a limited differential diagnosis. Keloids and hypertrophic scars occur at sites of former surgical wounds, lacerations, or areas of inflammation. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP) is a benign inflammatory condition where papules cluster in areas of prior striae. Cutaneous lesions of Behçet’s syndrome display pathergy, where pustular response is observed at sites of injury. Granulomatous infiltration in sarcoidosis may demonstrate a predilection for scars and tattoos (ie, scar or tattoo sarcoidosis).5 Sarcoidosis can have other cutaneous manifestations, including psoriaform, ulcerative, or erythrodermic lesions; subcutaneous nodules; scarring or nonscarring alopecia; and lupus pernio – violaceous, nodular and plaque-like lesions on the nose, earlobes, cheeks, and digits.5

Löfgren’s syndrome is a distinct variant of sarcoidosis.In 1952, Dr. Löfgren described a case series of patients with bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy and coexisting erythema nodosum and polyarthralgia.6 The epidemiology favors young women.7 Patients with Löfgren’s syndrome present acutely (as in this case), which differs from the typical subacute course observed with sarcoidosis. In addition to the classic presentation described above, patients with Löfgren’s syndrome may demonstrate additional manifestations of sarcoidosis, including fevers, peripheral adenopathy, arthritis, and granulomatous skin lesions. Painful symptoms may require short-term anti-inflammatory treatments. Most patients do not require systemic immunosuppression. Symptoms usually decrease over several months, and the majority of patients experience complete remission within years. Rare recurrences have been described up to several years.8

In confirming the diagnosis of sarcoidosis, current guidelines recommend exclusion of other diseases that present similarly, a work-up that generally includes compatible laboratory tests and imaging, and histologic demonstration of noncaseating granulomas.9 However, Löfgren’s syndrome is a notable exception. The constellation of fever, bilateral hilar adenopathy, polyarthralgia, and erythema nodosum suffices to diagnose Löfgren’s syndrome as long as the disease remits rapidly and spontaneously.9 Thus, in this case, although granulomatous infiltrates were confirmed on biopsy, the diagnosis of Löfgren’s syndrome could have been based on clinical and radiologic features alone.